Gamewright’s Jason Schneider on pitching, creativity and how working on Sesame Street helped shape his approach to product development

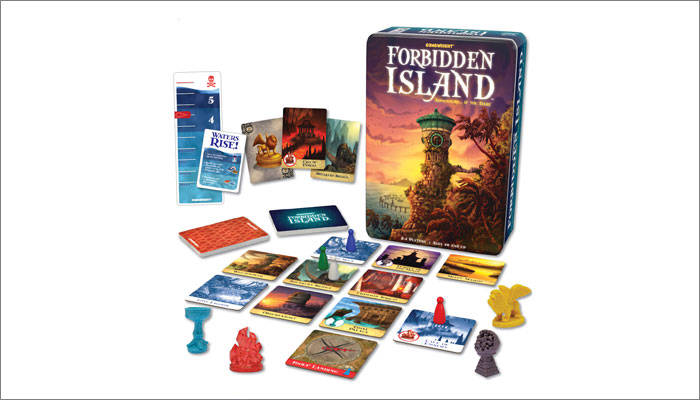

Founded back in 1994, Gamewright is the award-winning games company behind a raft of much-loved titles, including Sleeping Queens, Forbidden Island and Sushi Go.

This year sees Gamewright’s Vice President of Product Development, Jason Schneider, celebrate his 20th year with the firm, so we caught up with Jason to learn more about his path into games, why he loves working with inventors and what makes for the perfect pitch.

How did you get started in this industry?

Well I’ve been at Gamewright for over 20 years but I came here via children’s’ television. I started my career working in children’s television as part of the production team on Sesame Street. Right out of college, I got very lucky and got a job at Sesame Street where I learned a great deal about what it means to entertain on two levels; meaning to entertain kids but also ensuring adults are entertained too.

That’s been a guiding light for me as I maintained my career at Gamewright. I want to make sure parents and kids come together to enjoy an experience; not create something that babysits the kids or just entertaining the parents. I want to find, just like Sesame Street does, entertainment that works on two levels. I won’t lie to you; it’s challenging! It’s easy to find a great kids game or one that gets adults excited but to find one that makes both kids and parents happy, that’s what makes Gamewright tick.

That’s amazing! I think you win the honour of ‘coolest first job’! What did that role at Sesame Street involve?

I was a real hands on person there. My job was to work with the children on-set during the show tapings. I was there to direct them and, frankly, keep them from attacking the Muppets or ripping out Big Bird’s feathers; just keeping them in line so the puppeteers and the grown-ups could do what they were doing. It was a crash course in being disciplined and I got to watch some of the mentors that I grew up with execute their craft.

I was there a couple of years and then I moved from New York to the Boston area, which is where I am now, and I continued working in children’s television on another show that was a Nineties remake of a very popular here in the Seventies called ZOOM. It was a show where kids came up with ideas, submitted them and then other kids performed them. It was sort of a precursor to a lot of things you see today on YouTube with kids doing DIY crafts; ZOOM was ahead of its time in many ways!

At that time, Gamewright had acquired the rights to make ZOOM card games and board games. I’d always been a game lover and a tinkerer since I was a kid, so I used it as an opportunity to jump from the children’s TV world to the family board games world. That happened in 2000 so it’s a little over 20 years that I’ve been doing this. It’s been an amazing journey.

Well happy 20 year anniversary! Moving onto your day-job now, how do you and Gamewright work with the inventor community?

The first thing I’d like to say is that I really have an open-door policy – or an open e-mail policy! I take a lot of pitches, as you can imagine, and I look at pitches from pretty much anyone who sends them in. We get hundreds a year, which can be overwhelming at times, but I’m continually amazed by the creativity of people’s ideas; both the seasoned inventors but also those who just had a crazy idea and someone encouraged them to make it into a game and send it into us.

Many of my days are spent reading people’s pitches, looking at the potential of games and evaluating where a game could land in our line. I see lots of really great concepts but we only publish 8 to ten games a year. We’re getting somewhere in the vicinity of 400 or 500 pitches a year, so it’s not highly probable that your game turns into a Gamewright game, but it’s certainly a possibility.

We’ve got many, many games from first-time inventors that we’re really proud of and we continually encourage the community to grow by finding new and interesting inventors from all over the world.

And as well as first-time inventors, Gamewright has games from several big-name designers from the tabletop space; I’m thinking of Sushi Go inventor Phil Walker-Harding and Matt Leacock, who created your Forbidden trilogy of games – Forbidden Island, Forbidden Desert and Forbidden Sky – and who is also well-known as the designer behind Pandemic.

Yes, and Reiner Knizia – we’ve got some very well-established designers in our line.

These kinds of designers wear several hats as they create successful strategy-heavy games, as well as more family friendly fare; as a family games company, what’s the appeal of working with designers who may be more well-known working in the heavier hobby game space?

A great case study for this is looking at how we worked with Matt Leacock on Forbidden Island. I played Pandemic when it first came out and I was blown away by it. The design was fantastic, the experience was amazing, but I wondered how family-friendly a game like Pandemic was; not just thematically but in terms of the mechanisms. I thought ‘is there an opportunity to bring what was in Pandemic to a broader audience?’

So for the first time in my career, I commissioned a game. I contacted Matt out of the blue and said ‘I love your game and I’d love to work with you on something that I think could have a great impact on a different audience.’ We started right there and then on the seeds of what became Forbidden Island.

My approach is to look at games and look at some of the more complicated mechanisms that are out there, and figure out ways to make those mechanisms approachable to families who may not know that these mechanisms even exist.

Look at card-drafting. It’s a term that’s well-known inside the board gaming community, but if you go to your average family and say ‘we’re going to play a card-drafting game’, none of them have any idea what that means. Phil Walker-Harding did a brilliant job of distilling down what that mechanism is in Sushi Go, which is what we call a ‘pick-and-pass game’ – you pick a card and you pass your hand to the left. It’s a great example of translating some of these complicated mechanisms to a broad audience.

Our most recent example of this is a game we just launched called Abandon All Artichokes from Emma Larkins. She’s a relatively new game designer but a really smart one. Her idea was to make a approachable deck-building game. Again, what does ‘deck-building’ mean to families who only knows UNO, Crazy Eights or Solitaire? Abandon All Artichokes is a ‘my first deck-builder’ for those who know the lingo, but for those who don’t, it’s an exciting new way to play with cards.

The encouraging thing about that is that there must be loads more mechanisms and staples of the hobby space that are ripe for a family-friendly, approachable revamp.

Exactly! We are proudly a gateway game company. There are companies out there that are much better at making complex, heavier games. We like to get families excited about playing games, period. As you know, it’s so difficult to find time to pull away from a screen to play with some cardboard and wooden bits, so our goal is to say ‘hey, check out this new game that’s not the same as what you played with your grandparents, or what they played with their grandparents – it’s a new idea that will broaden your horizon with regards to what it means to play a board game or card game’.

That’s a brilliant summation of what a ‘Gamewright game’ looks like. Has that, or your approach to working with inventors, changed and evolved much over the 20 years you’ve been with the company?

Gamewright is a little over 25 years old and in the early days, when it was owned by a different set of owners, there was an ethos that, for the most part, if the game wasn’t invented in-house, then it wasn’t getting made by Gamewright. That was a bold statement to make and worked for a while, but it wound up being very limiting. There’s a cap on people’s creativity – there’s only so much that a bunch of individuals sitting in an office can do together. When I came on board, the company decided to broaden its horizons, look beyond the office walls and found an incredible well of creativity in the inventing community that continues to overflow.

That being said, I feel for the inventing community because there’s just so many great ideas coming at us, left and right, everyday. It’s only helped to raise the bar; we’re living in the golden age of board games and the bar is continually rising, so inventors keep having to step up their game, to use the pun.

Over the past 20 years, I’ve seen an absolute outpouring of amazing game ideas, to the point where we just can’t publish them all. Every year, we have to whittle it down to 8 to ten games, but there’s easily double that, if not more, that I think are great and worthy of publishing. It’s more about bandwidth and not wanting to oversaturate the market, so that each game we do publish gets a chance to shine.

I think you know that one issue publishers face is the glut of games that are on the market and how hard it is for a new game to get traction. We put out 8 to ten new games a year and most of our competitors do the same, so by the end of the year you’ve got hundreds, if not thousands, of new games hitting the market, in addition to the tried-and-tested classics and the ones that came out the year before! Finding games that will break through that noise is a challenge and will remain a challenge as we continue to do what we do.

I always encourage game inventors to think about that; what is it about your game that will break through? Is it a novel mechanism, the story, the unique components or is it just so simple and compelling that you can’t deny it? I used to like to say that Gamewright games are known for being tattered and played to bits versus ones that just sit on the shelves gathering dust. That’s harder and harder to say with the number of games out there but it’s still our aim, and we love it when someone says to us ‘we played Sleeping Queens 500 times, our deck’s tattered and we need a new one.’ That’s a real tribute to the game.

Every company has their own preferred way of receiving pitches, but what for you makes for a perfect pitch?

A perfect pitch is one that is able to crystallise what makes the game tick and get me excited about the game within the first 30 seconds of playing it. I read a lot of rules, that’s mostly the way I learn about games, and I can usually tell whether a game is a good fit for Gamewright within the first few sentences of reading the overview. Of course, I do my due diligence and read the rest of the rules thoroughly, but usually it’s got to have this je ne sais quoi excitement factor about it that has me at the get-go.

I see a lot of digital pitches and I’m seeing lots of video pitches which is great. I also read a lot of one-sheets and rules about games, which are a very typical first entry point for us looking at a game. If I see something that sparks that magic, that’s when I’ll request a prototype to bring in and test, and we do pretty thorough playtesting with families. We try to get honest feedback.

I want parents to be as excited about these games as the kids are. It can’t always happen, but that’s the aim. I always say the perfect Gamewright game is one that a parent will want to play with their kids after dinner before bedtime, but when the kids are in bed, they’ll continue playing with their partner because it’s so fun. Games like Sushi Go and Rat-a-Tat Cat really have that essence; they’re kids’ games that are really grown-up games too. That’s a Gamewright game in a nutshell, and it’s a challenge for sure. Sometimes when I talk to inventors about this, it makes them pause, because they might be really good at developing kids’ games or adult games, but it’s harder creating one that has a dual nature to it.

That dual nature point goes back to what you were saying about Sesame Street working on two levels. Is there anything else back from your time with Big Bird and Elmo that has informed what you look for in games?

Absolutely – it’s that element of surprise; that moment you don’t expect to capture your attention, but it does. I try and find games that have this element of surprise in it and because of that, I usually look for games that have a decent amount of luck in them. Of course there can be some planning involved, I mean, ask anyone who has organised a surprise party – it takes an amazing amount of planning! But that effortless-ness of a surprise can capture a special moment in board gaming that keeps people coming back for more.

You see so many games every year; how do you keep the experience of evaluating games fresh for you?

I try to approach every day like a child does; I try not to think too much about what I’ve seen previously and be in the moment. Of course, I can’t avoid looking at the past, especially if someone presents a game that is exactly like Crazy Eights and we published it, the world would look at it and say ‘that’s just Crazy Eights!’

But I try to not forget about wonder when I’m looking at new games and new concepts. Adults have much to learn from children about being present, being in the moment and embracing whim.

It’s also important to look at other forms of media and culture. I’m a big fan of music and I always have music buzzing in the background when I’m looking at games. A good song that catches me off guard and has me singing the lyrics could put me in the right position to evaluate a game when it comes through.

I’m also a big fan of animation and I love well-crafted animated movies and TV shows. There’s a lot we can learn from that world because it has done a brilliant job of operating on two levels and broadening our imaginations, even just aesthetically. Recently I saw Trolls: World Tour, which I thought was just okay from a narrative perspective, but aesthetically I thought it was a home run. I loved the look of that and thought, wow, what if we took that aesthetic and brought it into board gaming. Great aesthetics play a big role in what people love about games. People judge games the same way they judge books, by their covers.

Brilliant, thank you so much for this Jason, it’s been enlightening! Earlier you mentioned having an open-email policy, so I can’t let you go without asking how interested inventors can reach out to you?

Absolutely, we have a submissions email address which is [email protected] which is where people send ideas to. We’re open to collaborations and I love working with new people.

I travel several times a year – or at least I did before the pandemic happened – and would go to Essen, Nuremberg, Gen Con and I even went to the UK Games Expo for the first time last year. I love meeting new game designers and illustrators, and encourage those on the side-lines to jump in and reach out to us because we’re always on the hunt for great new concepts.

Amazing, and one last question; would you ever been tempted to go full circle and do a Sesame Street game?

I have, and quite honestly I’ve always been a little intimidated by it! Maybe it goes back to my early experience there, but it’s such a tall franchise in the eyes of world that I wonder could we do it justice in board games.

I’ve seen lots of Sesame Street board games out there, but for better or for worse, Sesame Street set my bar and personal expectations pretty high so I think I might go crazy trying to match that if we got the license.

But yes, it’s occurred to me several times and quite frankly, if we were approached to do a Sesame Street game, I’d be honoured to; I’d just have to think long and hard about how we’d bring the magic of Sesame Street to the board gaming world.

Amazing; well let’s watch this space! Thank you so much again Jason, hopefully catch up again soon.

—-

To stay in the loop with the latest news, interviews and features from the world of toy and game design, sign up to our weekly newsletter here