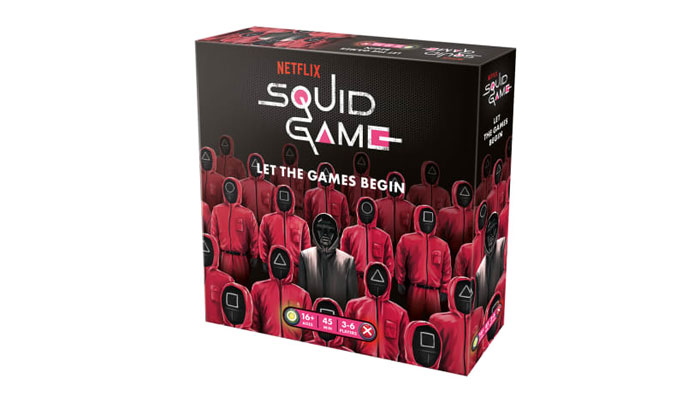

BlueMatter Games’ Rebecca Bleau and Nicholas Cravotta on designing Asmodee’s Squid Game board game

Guys, it’s great to chat! You’re no stranger to Netflix adaptations, but your latest licensed game is an adaptation of Squid Game – I’m on board! What came about first, the game or the licence?

The game and licence came about simultaneously. When Squid Game went viral, there was a very short window in which to get it into the 2022 production queue. By very short, we mean there was about a week to get everyone involved on board!

A week! Wow!

Yes! We put together a framework for the game that everyone could agree on, then started hammering out the details.

The show sees hundreds of cash-strapped contestants compete in deadly versions of popular children’s games until there’s one survivor left to win the cash prize. Talk us through how you went about translating the games from the show into formats that would make sense at the tabletop.

The three of us – Rebecca, Nick, and Skylar – worked as a team to develop this game. Skylar is our adult son, and he’s been watching us design games for most of his life. This is our second full collaboration with the three of us.

Sometimes we worked alone, in pairs, or all together. This gave us seven different POVs or ways to approach the design process. We were able to put a lot of ideas out on the table and pick the best ones.

We also focused on the experience. While most people have absolutely no interest in participating in an actual death game, they are intrigued about what it might feel like to be in one. We wanted to make a game where you feel a delightful edgy, tense anticipation as you wonder whether you will survive.

And, just like the show, you can help each other. But of course, everyone knows that at some point your allies are going to turn on you.

I imagine each game lets you flex a different design muscle…

Yes, each of the six games has a different feel, just like the show. There’s a blend of strategy and luck with a whole lot of bluffing and double-thinking your opponents. We abstracted the violence, but not the ruthlessness. During playtesting, we found that even people who didn’t like the violence and never watched the show enjoyed themselves and become thoroughly engrossed in the drama.

High praise indeed! Let’s delve a little into each game. The show kicks off with Red Light, Green Light…

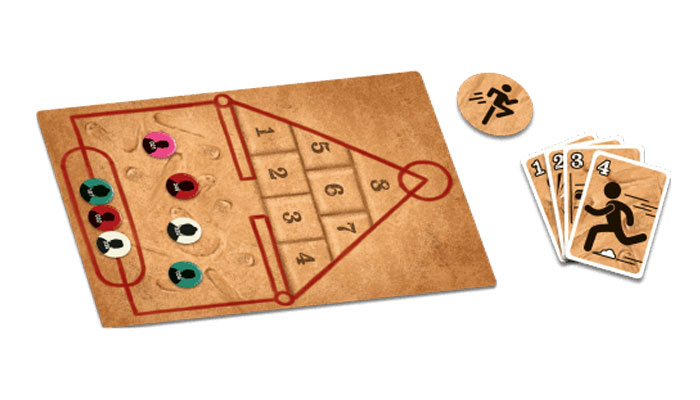

Red Light, Green Light is a mad dash across the field. Go too quickly and the Doll will see you. Be too careful and you’ll run out of time. We wanted to capture the element of cooperation, such as when 456 is saved by another player. Of course, you also have the option of giving a player in front of you a little push to knock them off their feet.

Of course! Then there’s Dalgona, the game where players have to carve a shape out of candy without cracking it. On paper that sounds like a tough experience to translate into a board game.

Yes, Dalgona was a challenging game to design. We considered a ‘drawing inside the lines’ mechanic but had to drop this. The main issue was how to determine if a player ‘cracked’ their dalgona. People have a hard enough time agreeing on whether a spinner is ‘liners’ or not. How would that play out if the group had to vote on whether you drew within the lines?

A second issue that affected design is that once you’ve seen the show or played the game, everyone would just pick the easiest shape to draw. We wanted to capture that same feeling of uncertainty when the players in the show pick their shapes but don’t know what they’re getting into. We also thought it important to work in a cooperative aspect, the ‘kick the lighter’ element the show has.

A third issue is that players have multiple team members at this stage, each of whom has to make their way through the game. The final game design utilises a ‘guts’ dynamic combined with a time limit that allows players to press their luck. In this way, there’s the feeling of surprise… Will I crack my dalgona? It also adds the pressure of having to move quickly.

And the design challenges don’t stop there – next up is Tug of War…

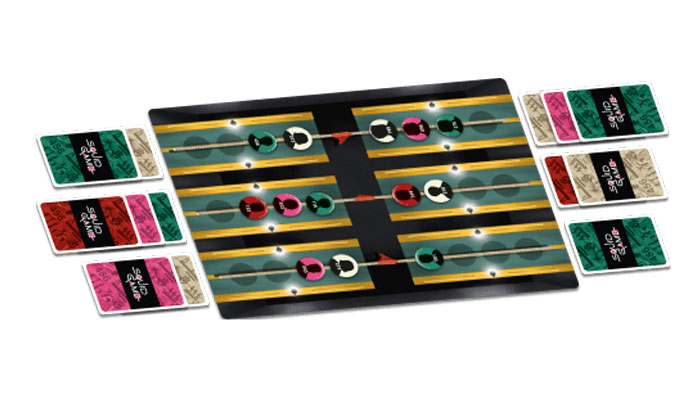

Tug of War was one of the more difficult games to balance. At first, it seemed simple enough. We went through many iterations to land on the final version.

One issue was how complex to make the game. Should we pull the rope space by space and eliminate players one-by-one? However, this added complexity and lengthened the game significantly. It also took away from the excitement as it was pretty clear how one team member against four would eventually pan out.

Another factor was designing the game so that a player with more tokens remaining couldn’t just overwhelm a player whose team was dwindling. Keeping the game fast kept the excitement up. Also, having three tug of war rounds to choose from increased strategy and cooperation between players.

Finally, being able to ‘drop the rope’ adds a delightful reversal for additional depth of strategy.

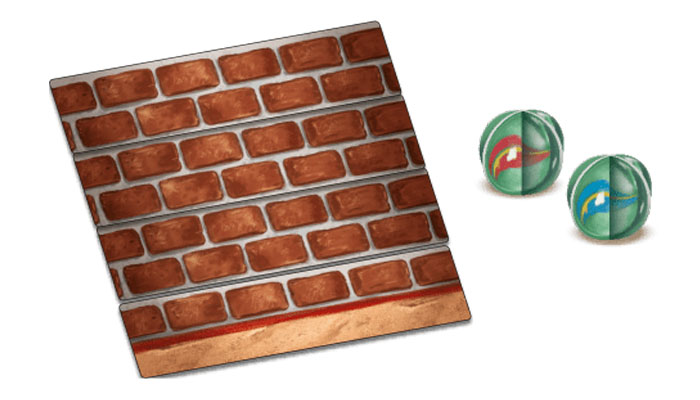

Nice. Then there’s Marbles. In the show, this game only involves two players…

Yes, and because Marbles is player vs player, it needed to be fast. In the show, there are several ways to play such as tricking your opponent, shooting marbles at a target, and making a guess of how many marbles a player is holding in their hand. We thought having two options – shooting and guessing – would capture the spirit of one-on-one battles in a timely fashion.

It’s surprising how intense the Marbles battles can be between players, especially if they have history between them. There’s definitely a “I’ll get you next time” angle to the game.

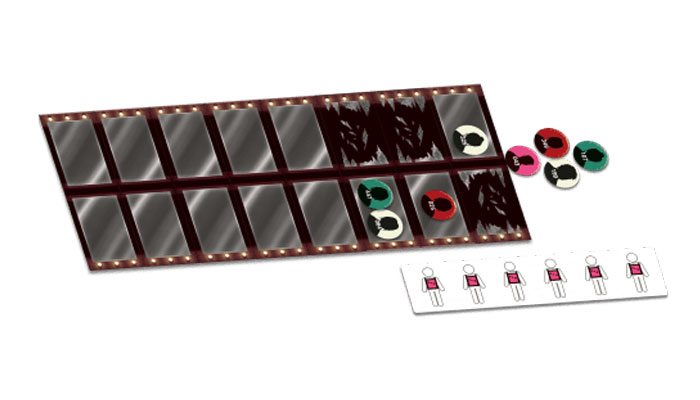

We’re at the penultimate game: Glass Bridge. This sees contestants attempt to cross two parallel bridges by jumping across glass panels; some are sturdy while others shatter under the weight of players.

Glass Bridge is the most involved game of the six. It’s also the most brutal. We spent a great deal of time working to capture the feeling of the show for this game.

Part of what made it difficult to design was how to get players to move ahead over the Glass Bridge. On the show, the initial players comply and try to cross the bridge in their given order even knowing that they are going to fall. Many game players don’t want to be forced to do something they don’t think is smart. There’s also not much of a game if you’re forced to cross the bridge in numerical order!

For this reason, we focused on how 101, the gangster boss, played. He didn’t care about order, and he had no hesitation pushing another player in front of him to test the glass. And, of course, when you do have to move across the Glass Bridge, there is the delicious moment of choosing which side you’ll jump to.

It does sound brutal. Speaking of which, we’re now at the Squid Game itself…

Squid Game had its own unique challenges. The rules are given at the start of the show – and they’re a bit complex and confusing. In any case, the final two players don’t actually play a conventional round of Squid Game – kids don’t play it with knives!

That’s a relief!

We quickly assessed that coming up with game mechanics for jumping on one foot and becoming the “Inspector General” would require more complex rules than we had space for, given this is the last of six games.

Instead, we focused on the core of Squid Game. In the final, frantic stage of the game, the two players are trying to reach the squid head. They make a run for it, try to push each other out the court, and even attempt to stab each other.

The final piece of design was bringing the entire story into the game. The experience starts with the rules, which include instructions and tips from Front Man. As you play the games, you can’t help but see how your team shrinks in size. There’s always an opportunity to work together, but backstabbing is always a compelling alternative. And, just like the show, you have to be careful who you trust.

The visuals play an important role in making Squid Game immersive and come alive. Your team members are running towards the Doll to survive. You physically flip over the Glass Bridge tiles to see if you survive or are eliminated. And each team member has money printed on the back so when they are eliminated, they are added to the giant piggy bank that goes to the final winner.

You also included the VIPs who watch the games here too right?

The VIPs were fun to work into the story as well. We don’t utilise the betting aspect because it’s much more engaging to fight for the survival of your team compared to betting on which players survive. Where the VIPs do come in is as spectators who mess with the players when they get bored. Tip: Don’t let the VIPs get bored.

I won’t! Now, was there anything about the show that – despite your efforts – just didn’t translate to the board game?

Technically, Squid Game is a death game, which means anyone who survives the final game wins. In playtesting, however, we found that multiple winners simply wasn’t satisfying. Nearly every player preferred a single winner.

And, with a game like Squid Game, winning is better when you’re standing on a mountain of your friends’ corpses. This visual image helped keep us on course whenever there were several ways we could proceed.

Ha! A gruesome but helpful anchor! And did any of the brand’s constraints prove helpful creative fuel during the design process?

Perhaps the biggest design constraint was creating six games that could be played in 45 minutes. This meant each game had to be simple with a few intuitive rules that are easy to learn. At the same time, the game needed to have enough depth to make it fun to play many times. By focusing on the experience, we were able to streamline game play and eliminate anything that got in the way of the fun.

So the ‘six games’ challenge actually paved the way for snappy, fun experiences. Great! Any other examples?

Well, the second biggest design constraint is that Squid Game is, by its nature, an elimination game. In the show, half or more of the players are eliminated each game. Not many people would want a game you have to invite 455 of your closest friends over for. Nor does anyone want to play a game where you can be wiped out in the first round and have to sit for the next hour watching everyone else have fun! We needed to devise a mechanic where lots of elimination is a core dynamic – without dropping players.

A fascinating problem to solve. What was the answer?

Rather than playing a single person, each player represents a team of players. Each game, members of your team can be eliminated. Many of them. To avoid knocking a player out of the game, each team recruits a new member between each game. This way, you always have at least one team member all the way to the end. Successful players will enter the final Squid Game with more players, giving them an advantage. Of course, players who are behind can work together to even out the odds.

We’ll have to start wrapping up but were there any other interesting challenges to overcome?

At the time of design, supply chain issues were at a head. Many companies were having difficulties sourcing components and getting product off boats and to stores.

We were given a list of materials and components we could use. We also had to create the game in record time to guarantee that product would be ready for delivery. It was an extremely compressed timeline, and Asmodee was an amazing partner to work with to achieve this.

Guys, before I let you go, I have to ask… Which out of the games in Squid Game do you think you’d have the best chance of winning?

Nick: I keep coming back to Red Light, Green Light. I’m fast on picking up rules and figuring out loopholes, and there are a lot of angles to exploit in this game, like hiding behind others. I also like the independence of the game; I’m not going to lose because someone on my team couldn’t pull their weight.

Rebecca: I would say Glass Bridge because this game is more about guts and wits than it is about strength or speed. Then again, maybe Dalgona because when I saw the show, I picked the circle.

Skylar: My best bet would be Tug of War because I look stronger than I am. That would increase my odds of convincing a strong team to accept me as a member.

Lovely stuff! Guys, a huge congrats on Squid Game! Let’s tie-in again soon.