Brett J. Gilbert lifts the lid on the design process behind his new game, Professor Evil and the Citadel of Time

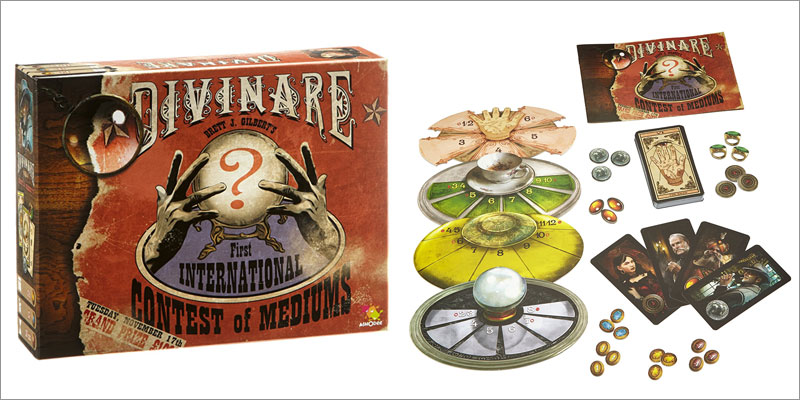

Cambridge-based Brett J. Gilbert landed in the world of game design back in 2012 with his first published game, Divinare. Brought to market by Asmodee, the game made Spiel des Jahres’ Recommended list, and Gilbert has since gone on to design, and co-design, titles for the likes of Mayfair Games, AEG and Space Cowboys.

Gilbert’s output isn’t easily categorised, spanning kids games like Karnickel and Serpentiles, strategy hits like the Kennerspiel des Jahres nominated Elysium, and even a two-player tile game created specially for iOS called Quarta.

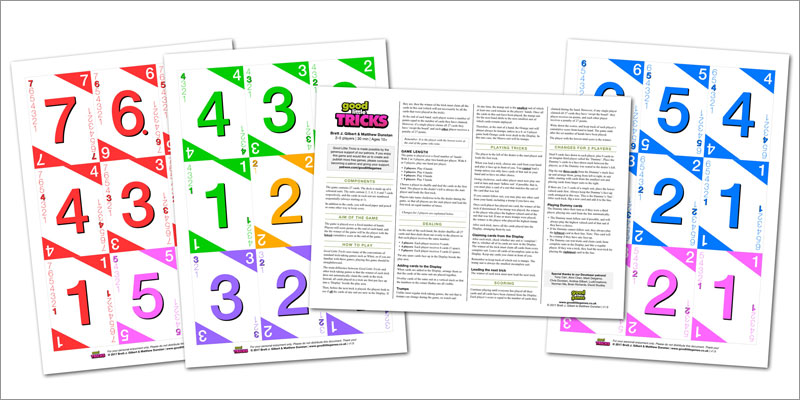

But as well as having games on the shelves, Gilbert is also the founder of Good Little Games, a publisher of free-print-out-and-play games. Gilbert first launched Good Little Games back in 2013 as a platform for free print-and-play ‘microgames’. An array of game designers contributed 11 games to the Good Little Games portfolio, which have since received a combined total of over 30,000 downloads.

In April 2017, fellow designer Matthew Dunstan joined Gilbert to re-launch Good Little Games and co-design each new title, supporting the venture via Patreon, a crowdsourcing website that allows anyone to make small pledges of support for creators of all kinds.

Good Little Games plans to release a new free print-and-play game each month, and so far, the firm’s line-up includes 15 titles, including Good Little Ninjas, Good Little Martian and Good Little Tricks (which some deemed a highlight of this year’s UK Games Expo).

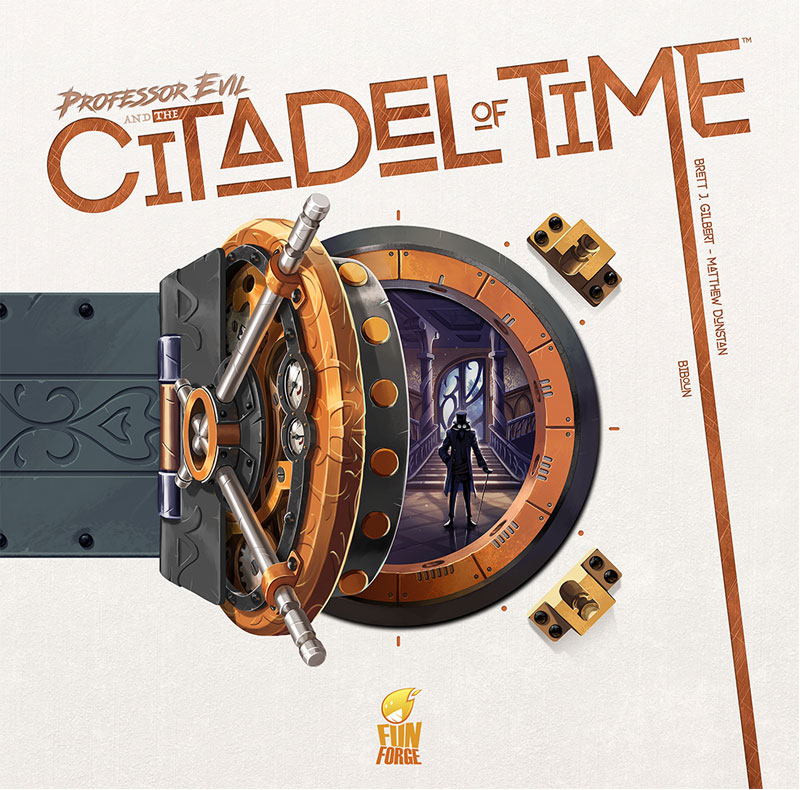

2017 has not only proved to be a banner year for Gilbert due to the return of Good Little Games but also because of the three new games he has hitting the shelves, including Professor Evil and the Citadel of Time, a co-op adventure co-designed with Dunstan and set be published by Funforge next month.

Below, we talk to Gilbert about the collaborative development process behind Professor Evil and the Citadel of Time, as well as discuss how he approaches designing games for children and the advice he’d give budding game creators.

How did you first get into game design?

I have always played games. As a child I played constantly with my friends, my sisters and my parents. And I think it came naturally, to myself and to my older sister especially, to imagine how we might change the rules of the games we played. It is a short step from that realisation (that you don’t have to follow the rules if you don’t want to!) to the notion of creating your own games.

I still have some examples of games I created when I was young. Recalling them now, I can see that they weren’t really any good at all – or at least, not remarkable – but the instinct was already there.

I didn’t return to game design until much later, and it has taken a long time for it to develop into a (precarious!) profession, but it was definitely in the blood all along.

How has your development process evolved between your first game and your most recent creation?

As with all professional creative endeavours, game design is a mix of art and craft – every project gives you more experience to draw from, teaches you more about the kinds of games you enjoy, and informs you more about your own talents and limitations.

I have a folder of partially or fully developed game design projects on my MacBook Pro that now numbers well over 100. Some have been or will be published; a decent number of the others are at least publishable. But many are now just relics of the journey; evidence of the path not taken and of a lesson learnt.

The ‘art’ will always be hard, but the ‘craft’ becomes, if not easier, then at least more familiar, more natural. And perhaps the most important thing I have discovered is what kinds of games and experiences feel most natural, most instinctive and most coherent to me.

You’ve co-designed a fair few games too. How does that collaborative process usually work or is it radically different with each designer you work with?

Co-designing has been hugely important and remarkably productive. Finding the right partner is one thing, but the trick is finding the way to work with them so that you can both contribute your best to each individual project.

A big part of this has been coming to understand which part of the design process I’m good at and finding partners who are good at the other parts.

I’m definitely more of an editor, a developer. I am a mathematician and scientist. I’m good at figuring out patterns and puzzles. Game design is all about systems and structure, but it’s also all about ideas and stories, too.

My experience of collaborating with different co-designers has been consistent, but I think the fundamentals of the process have to be the same for it to be successful. You won’t make a good designer if you’re not able to discard your own ideas. Co-designing is no different, but you have to go one step further and be prepared to let someone else throw away your ideas for you!

You have also designed games for a raft of age groups. How different is your approach when designing for kids?

Experienced gamers are familiar with a multitude of mechanistic concepts, and are eager to discover new ones – no matter how abstract or arcane! To more casual players – and to children especially – all of that is simply a foreign language.

So, when creating experiences for those players you can’t assume any of that language will be understood. You have to work from first principles. This isn’t ‘dumbing down’. Kids aren’t stupid; they understand plenty and they see things plainly and directly. They know the difference between work and play, and they know when they are being patronized.

So the process isn’t any different, it’s just much, much more difficult.

Could you talk us through the development process behind one of your recent creations and some of the key design choices behind it?

Professor Evil and the Citadel of Time, co-designed with Matthew Dunstan, will be published by Funforge and Passport Game Studios in August 2017. The game came to life at the start of 2014 in the same way that almost all of our collaborations have started: a short conversation followed by a slightly scrappy prototype, hastily and wholly built by Matt, and put together just in time for one of the regular playtesting meet-ups in Cambridge.

Getting something – anything! – to the table as soon as possible is absolutely best practice. You have to be prepared for failure, but in this case the core idea of the game instantly connected with our pioneering playtesters and even this very first game was fun. That’s definitely not always the case (!), but the first step in this game’s development was hugely encouraging.

The next step was then for Matt and I to dissect the experience, and to push on to a new iteration of the prototype as soon as possible. At this point in the process, details are changing rapidly, with additions and subtractions being made quickly, all the while swirling around the core idea.

This is when co-designing can be at its most productive. Every new angle or direction that either of us proposes immediately gets sanity checked by the other. Resistance to an idea can lead to a counter-proposal. That shift can lead to another insight. We may both have different details of the game that we personally champion, but being forced to defend your position also forces you to interrogate it. All of this is tough to achieve so speedily when designing on your own.

But only playtesting has the power of genuine revelation, and the weekly playtesting sessions were invaluable. They are also a good taskmaster, since if you don’t get your homework done before next Tuesday you won’t be able to playtest.

The game is a co-operative adventure, and an crucial part of the game are the player characters and the small player decks that give each character a unique set of different skills. Refining these was an almost endless process, which continued after we successfully signed the game with Funforge in 2015. Each action had to earn its keep and with such small decks, only the fittest had any right to survive. Continual playtesting helped us to find the focus these decks needed, as did the excellent development work undertaken by Funforge, who really pushed us to streamline and refine ever single part of the game.

They challenged us to address their concerns about game length and complexity, but were always mindful that the game had a spark and a spirit that we all needed to be careful not to compromise. But that’s the trick with development: sometimes you need to tread lightly or risk diluting some of the alchemy that made the game work in the first place; but there are also times when only bold steps and radical rethinking are enough.

How do you stay creative? Where do you find inspiration?

Two excellent questions to which I don’t have good answers! And one trick I’ve learnt is to collaborate with people who have more ideas than I do. Being creative is much easier for me once an initial trajectory has been established. Making something better out of something good is so much easier than making something good out of nothing!

Inspiration can come from anywhere, but I am a visual thinker, so one way I can foster ideas is to keep a notebook and pen handy and give myself time to draw pictures and doodle. And for me, train journeys are an excellent catalyst!

“NEVER SPEND ANY REAL MONEY. MAKE YOUR PROTOTYPE OUT OF SPIT AND TWIGS AND GET IT PLAYTESTED AS SOON AS POSSIBLE, WHILE BEING READY AT ANY MOMENT TO THROW IT AWAY.”

Do you think the games space in a good place creatively at present? What titles have you enjoyed recently?

Board games as a hobby is growing. Younger people are rediscovering the joy of analogue play. The board games aren’t going to slay digital games any time soon, but fashions and people change, and right now there are more games, more publishers, more players and more awareness of games and play than ever.

I don’t play an enormous number of brand new games, partly because finding time to playtest is always a priority, but also because I know that the vast majority of them are simply not my cup of tea. I read about them, or talk about them; read the rules or watch a playthrough on YouTube — and that’s very often enough for me. There’s much to learnt and understood but I don’t feel I have to play them, and in most cases I certainly don’t feel compelled to. It’s possible that makes me an idiot.

But I wonder if all designers feel the same? (Not that they are idiots; that they don’t need to play a game to understand it.) And without some arrogance and self-belief that you can do even a little better than what’s already out there, why would you make games in the first place?

What advice would you give someone trying to get their game concept off the ground?

Never spend any real money. Make your prototype out of spit and twigs and get it playtested as soon as possible, while being ready at any moment to throw it away.

As soon as make your prototype into an asset, you instantly surrender some of your own power to change it. You will find yourself defending its flaws, overlooking its failings, and clinging to its value not its worth.

So, be smart: be thrifty!

What can we see hitting the shelves from you this year?

There are a trio of games coming this year that I am very excited about. Professor Evil and the Citadel of Time, designed with Matt Dunstan and coming from Funforge is the first, and it’s going to be a beauty!

And I have two new games due for release at Essen in October, a super-fun dice game from Zoch Spiele, designed with Trevor Benjamin, and a more meaty city-building card game from ABACUSSPIELE, again designed with Matt.

Unfortunately the names of these other two games are under wraps for now, but both of them, along with Professor Evil, are some of my own absolute favourites — indeed, some of the best games, period — I’ve ever designed.