Cluedo at 75: The history and mysteries of the boardgame Clue… And why the inventor vanished!

It was Mr. Gold, in the gun room… With the hypodermic syringe! Wait… What?! While there’s something jarring about those words, they were nearly a possible outcome in the original game of Cluedo. Known as Clue in the US, the inventor’s patent for the game of who done it, where and with what shows a number of intriguing differences to the published version. Three quarters of a century on, this piece finds out why…

Happy 75th. Or 80th, maybe!

Cluedo’s 75th anniversary is passing with surprisingly little fanfare. One reason for this is likely to be the difficulty of locking down an exact date on which to cheer. That’s because, as with many of these classic games, there are a number of landmark dates in the diary – but some of them seem like wobbly pegs when the time comes to hang your hat.

So… From where should one start counting? The year in which Cluedo was devised? Patented? First released? Things being what they are, people tend to plump for 1949. Why? Because on November 9th of that year, Waddingtons wrote to the inventor notifying him that the game would go on sale “in about three weeks”. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves – indeed, let’s go back to the beginning…

Murder!

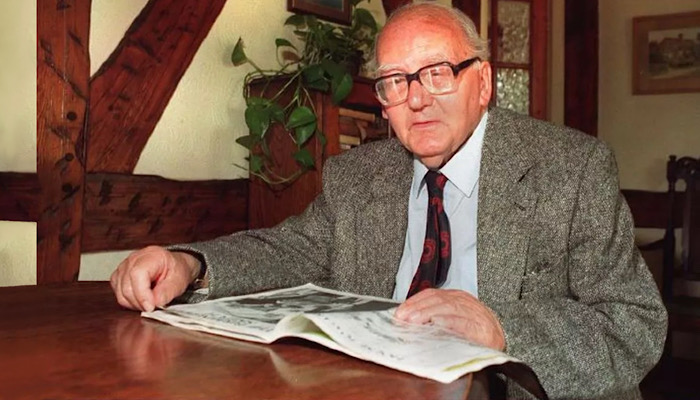

Provisionally patented as Murder! in 1944, Cluedo is the brainchild of a man with a somewhat unfortunate name: Anthony Eustace Pratt. Interestingly, it transpires that, for reasons unknown, Anthony didn’t care for the name Eustace – and instead took to using his father’s middle name: Ernest.

In any case, Anthony based his idea for Murder! on a popular parlour game of the time. The format of ‘Murder’ was much the same as a modern Murder Mystery night. A mix of guests and actors would find evidence of foul play after a supposed victim playacted their demise… Falling to the ground with a scream before the rest of the group set about discussing and deducing who was responsible for this murder most horrid.

There’s no doubt that Anthony Pratt saw plenty of people playing this. Before the Second World War, he earned a living composing music and playing piano recitals on cruise ships and in country hotels. Anthony waxed lyrical about this time when he reflected on it many years later… He told reporters: “We lived like lords. Then came the war and the blackout – and it all went, ‘pouf!’ Overnight, all the fun ended… We were reduced to creeping off to the cinema between air raids to watch thrillers.”

Of course, this parlour game hadn’t become popular in isolation. In the early 1940s, detective stories were still in huge demand – and Anthony read such books avidly. In particular, he relished the novels of Dame Agatha Christie, Raymond Chandler and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

Murder Most Florid

Christie and Doyle’s names alone are enough to conjure up a taste of the times – and the tomes! How many tales penned during the so-called Golden Age of Detective stories are set in a baronial country mansion? How many depict a glamorous lifestyle in florid terms before contrasting it with slaughter and the genre-defining question: “Whodunnit?”!

Little surprise, then, that Anthony – a Machine Tool Fitter in a munitions factory due to his poor eyesight during the war – found inspiration in this material. But closer examination of the patent he submitted on Friday the 1st of December 1944, reveals intriguing differences between it and the game published by Waddingtons some five years later. Indeed, a good deal changed in regard to the who, the what and the where…

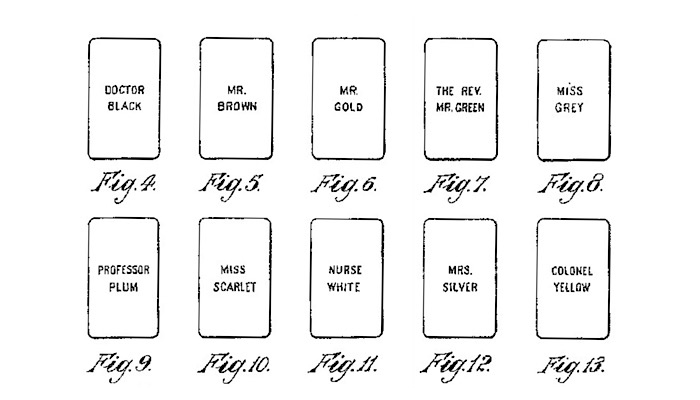

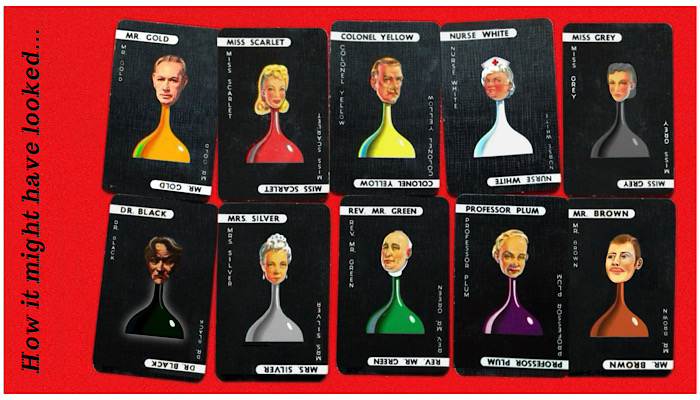

Who?

Glaringly, there are ten characters in the original line-up of suspects – not six! Alongside The Rev. Mr. Green (sic), Professor Plum and Miss Scarlet – with one t – are two familiar-but-odd names: Colonel Yellow and Nurse White. After that come the totally rejected Mr. Gold, Miss Grey, Mrs. Silver, Mr. Brown and Doctor Black. It was proposed that any one of these ten people would be bumped off at the beginning of each game – and up to eight of the others would then investigate the death.

However, ten potential characters must’ve looked rather unwieldy to the eventual-publisher Waddingtons. In trimming things down to six, Dr. Black lost his qualifications and became – in the UK version – the perpetual victim of the game. Yes, in Cluedo, it’s always Mr. Black’s cadaver that’s discovered on the cellar stairs. Meanwhile, Colonel Yellow and Nurse White were renamed Colonel Mustard and Mrs. White respectively. The other four characters were dropped completely – with Miss Peacock taking their place.

Meanwhile, the US publisher – Parker Brothers – had concerns. They were already nervous about putting out a game with the theme of murder… And positively quailed at the idea of portraying a parson as a person suspected of the deed! Their cold feet and curled lips swiftly led to the character’s transatlantic defrocking. Finally, Parker Brothers also chose to change the name of the victim. In America, the corpse is known by the conspicuously colourless name of Mr. Boddy.

What?

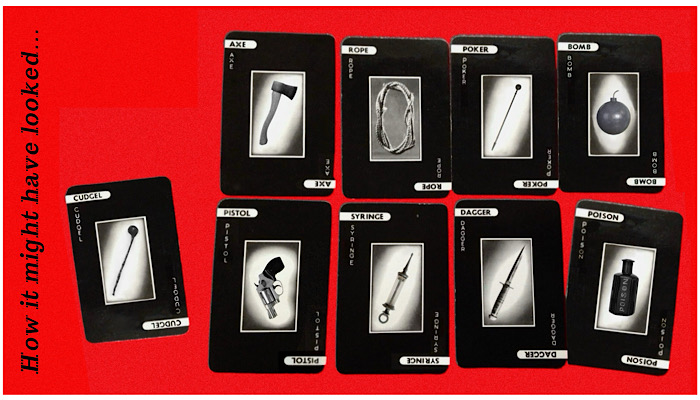

Clue and Cluedo, as we all know, traditionally contain six weapons. The first three were always on the cards: a rope, a dagger and a revolver – or pistol.

Later additions – of which Anthony’s patent made no mention – were the candlestick, lead pipe and spanner – or wrench. So far, so familiar! Originally, though, Anthony wanted nine weapons. His other choices were all eventually dropped, but we mostly know what they were from his sketches. There was a hypodermic syringe, a poker, a bottle of poison, an axe, a bomb and what looks like a gnarled stick…

That final weapon – Fig 33. – remains something of a mystery: the patent doesn’t actually name it as a cosh, cane or cudgel! Rather, it’s left to our imaginations to identify it. However, better minds than mine have pondered this question, and one fan site – www.cluedofan.com – proposes that it’s a specific type of wooden stick called a shillelagh – pronounced ‘Shuh-lay-lee’.

A shillelagh is a stout length of oak or blackthorn, characterised by knobs and knots. In that respect, it’s fair to say two things… First, that Anthony’s drawing does bear some resemblance to a shillelagh. Second, that some walking sticks have evolved following a shape similar to these ancient Irish weapons. For those reasons, it’s easy to picture a shillelagh being on hand in the rooms of some muck-a-muck’s sprawling country mansion. Of which…

Where?

It’s widely believed that the house named in Cluedo’s rules – Tudor Close, today known as Tudor Mansion – was inspired by Highbury Hall near Birmingham. This Grade-2 listed building is a little over a mile away from the leafy suburban address at which the inventor then lived… 9, Stanley Road, Kings Heath – just outside England’s bustling second city. Meanwhile, The Tudor Close Hotel in Rottingdean, on England’s south coast, also claims to be the inspiration!

While the name certainly fits, this makes less sense to me. Would Anthony really have sought inspiration from a house 156 miles away from his own when Highbury Hall was almost visible from his upstairs window? The claim is, however, that Anthony played one of his many piano recitals in Tudor Close – and since that is a distinct possibility, the mystery endures.

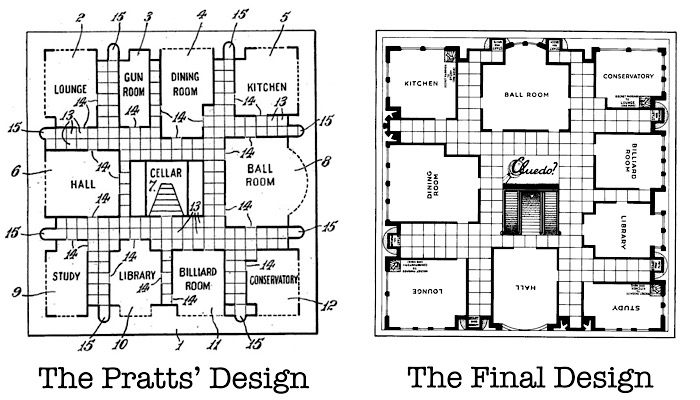

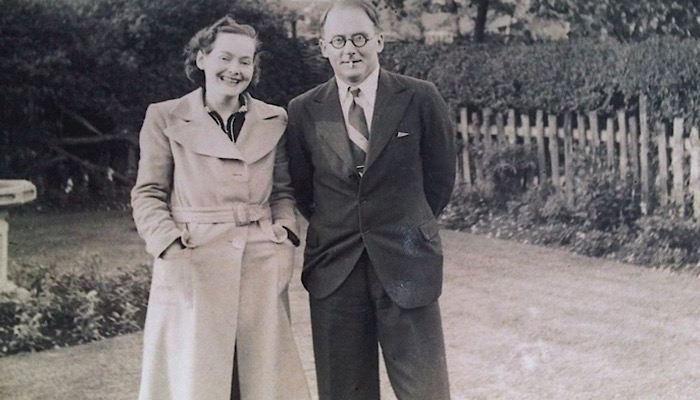

In any case, Cluedo’s iconic board was designed by Anthony’s wife: Elva Rosalie Pratt, née Hill. They married on Sunday December 14th, 1941: exactly one week after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in the US. The couple were no strangers to bombs closer to home, either… Nearby Birmingham was the third-most-bombed city in England during the blitzes – with Kings Heath itself repeatedly taking a pummelling throughout 1940.

Indeed, it was due in no small part to the boredom the couple experienced during countless air raids that they began working on Anthony’s idea for a boardgame. By 1943, things were progressing nicely – and their vision for the rooms remained almost exactly the same in the final design. In fact, the original had just two additions…

First, there was a gun room! On the board, this nestled between the lounge and the dining room. Second: the cellar. In the published version, this is a unique space; a decorative staircase with an X… It’s where the body is found and the Envelope for Murder Cards rests. In the patented version, both these rooms are drawn with access points and appear to function just like any other room.

However, while the extra rooms are included in the board’s design, neither has a card assigned to it. That makes it unclear whether Anthony intended for them to be used as regular rooms, or whether the cards’ omission suggests he’d already decided to get rid of them. Either way, the elimination of the two spaces as potential murder scenes makes the game much more manageable from a design perspective. Here’s why…

What if Anthony had gone ahead with his original ideas, and those two extra rooms had cards? Well… That would mean every game of Cluedo would’ve had a potential 990 possible room, weapon and murderer combinations. Granted, this would’ve dropped to 891 as soon as you started to play… But that’s still a huge number of outcomes – and would make for an interminable game. This becomes all the more apparent when you consider that the published version can last nearly an hour with a mere 324 possible combinations!

What Waddingtons Wanted…

Founded in the late 1800s, Waddingtons was – by 1946 – a huge British printing company with an august reputation. They were famous for being the UK distributor of the smash-hit game Monopoly. They also produced Lexicon, along with stunning cigarette cards and extremely high-quality playing cards. You can read a conversation with members of the family that ran Waddingtons here. Suffice to say, all this meant Waddingtons was an excellent choice for Anthony’s invention – and it makes absolute sense that he approached them…

However, there’s a little more to that decision than meets the eye! As Anthony told the story, he was leaning on the fence talking to his neighbour about how the Second World War was killing the country’s social life. The man on the other side of the fence was his friend Geoffrey Bull – inventor of the highly successful swashbuckling game Buccaneer… Published – of course – by Waddingtons.

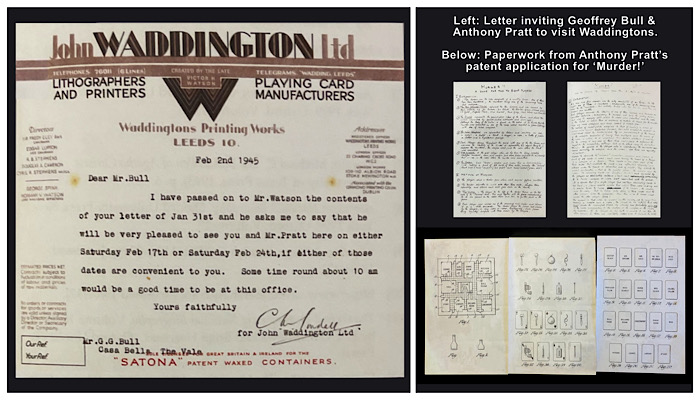

As a result of this serendipitous connection, Anthony and Geoffrey were both invited to meet Norman Watson, then Managing Director at Waddingtons, in Leeds, at 10am on February 17th, 1945. The two men travelled to the meeting by train, carrying both a prototype and the patent. Once there, all three played the game. And while Norman Watson certainly had concerns about the idea, he could see its enormous potential. Nevertheless, it still took a short while to make an initial decision on the matter: Waddingtons officially approved the game on June 26th of the same year.

Unfortunately, post-war shortages meant it would be four more years before Cluedo actually limped to market – by which time Waddingtons had made several changes to the rules, layout and design. For the most part, these enhanced Anthony’s thinking – retaining its genius, but speeding things along more agreeably.

Changes: The Name of the Game

Changing the name of the game is probably the most conspicuous difference of them all… And such an important one that they changed it twice! So how did we end up with Cluedo in the UK and Clue in the US? Well, in the UK, the game Ludo – Latin for ‘play’ – was already a household name. In some countries, however, it was far better known as Pachisi – the Indian game from which it originated. So Waddingtons wanted to capitalise on Ludo’s popularity in the UK – meaning Cluedo worked well and stuck fast! The US couldn’t do that – so they simply dropped the ‘do’.

Other Changes

While the patent proposes nine weapons, eleven room and ten potential suspects, it clearly states that Cluedo is for two to eight players. There were also only eight starting spaces… It seems that – having chosen a victim card – up to eight of you could then pick which of the remaining nine characters you wanted to play as… And then simply leave one aside. Waddingtons refined this by streamlining it to nine rooms, six suspects, six weapons and one ever-doomed victim.

Anthony also proposed that – after taking out the victim, murderer, weapon and room cards – the rest of the decks be dealt into the rooms. Everyone then had to visit the rooms in order to pick up cards.

Similarly, when you wanted to make a suggestion, you had to catch up with your suspect! You then moved them and the weapon of choice to the appropriate room. It’s also worth noting that the characters were represented by different-sized pawns: taller tokens for the men, shorter tokens for the women.

It also appears to have been Waddingtons that introduced the idea of secret passages. This, it has to be said, is a mercifully efficient way to move from one side of the board to the other.

One final rule change of note: in the original design, there was a limit as to how many times you could ‘make a suggestion’. You kept track of these with 15 counters each; distributed by the dealer at the start. When you ran out of counters, you could no longer make suggestions.

Selling the Rights

On occasion, controversy swirls around the question, “How much money did Anthony Pratt make from Cluedo?” That’s because the answer is: nowhere near as much as he might have. Following the birth of his daughter, Marcia – and a reported downturn in US trade – Pratt outright sold the foreign-sales rights to Waddingtons on 14th May 1953. The price? £5,000 – roughly $14,000 at the time.

Now, to be clear: £5,000 was a good deal of money in those days. Anthony also continued to receive royalties from the UK version until the patents expired in 1967. However, there’s no denying that those overseas royalties would’ve made him enormously wealthy had he retained the rights.

Life After Cluedo

In 1956, Anthony and Elva – who by then had already moved house twice – bought and ran a sweet shop and tobacconist at 19, Priory Road, Alcester in Warwickshire. They stayed in Alcester for three years, changing houses only once in that time, before moving again – in 1959 – to the idyllic south-coastal town of Bournemouth. Here, they bought Hathaway Cottage: a positively stunning house in Surrey Road, complete with self-catering holiday flats which they let out. The family continued to move house with surprising frequency – with Anthony briefly returning to work as a solicitor’s clerk before retiring.

The Patent Expires

Occasionally, one does hear the rumour that Anthony died embittered and impoverished. Neither of these things are true. What is true is that the Pratts moved back to Birmingham in 1980 shortly after Cluedo’s patents expired. But by his own account, Anthony was still happy with his lot when he gave an interview ten years later… In 1990, Pratt told reporters about the day a letter came with his final royalty cheque and the news that,

“…there would be no more ‘because the patents had lapsed’. That was that. We didn’t mind, you know… It had been one of life’s bonuses. A great deal of fun went into it. So why grumble?”

Anthony’s daughter, Marcia Davies, also spoke of this sanguine attitude in a 2009 interview. She told reporters:

“£5,000 was a lot of money back then – you could buy a good house with that. It was only in the Sixties, when there was rampant inflation, that my parents’ nest egg was severely eroded and wasn’t worth so much anymore.”

With all that said, it seems that Elva was somewhat more chapfallen about matters. She felt that Anthony had been swindled out of the overseas’ royalties. It understandably rankled to see Clue going from strength to strength without commensurate reward for the inventor. But what was done was done, and – having unsuccessfully tried to invent a couple of other games over the years – Anthony Pratt all but vanished from the toy and game industry.

Hasbro Buys Cluedo

In 1994, the toy giant Hasbro bought Waddingtons Games for £50 million. They had also purchased Parker Brothers three years earlier, meaning that they now held the worldwide rights not only to Cluedo but also Monopoly. It’s fair to say that it was Hasbro that fully realised the potential of Cluedo and Clue… Under their stewardship, Anthony’s invention became a behemoth IP. The game has inspired films, plays, books, a musical, TV shows, spin-offs, countless lifestyle products and innumerable licensed versions. Regrettably, though, there’s a toe-curling epilogue to the story…

Epilogue

In 1996, the Waddingtons Games brand launched a campaign to try and locate Cluedo’s long-lost inventor. Astonishingly, this was to celebrate the sale of the 150 millionth copy of the game. To that end, they opened a ‘Cluedo Hotline’ to obtain information about Anthony Pratt’s whereabouts. The press release for this began quite playfully: ‘Wanted: For Murder Most Enjoyable’. Even at the time, though, this tone must have struck someone – surely – as a little ill-advised? Had all been well, Anthony and Elva would, at best, have been of advancing years by then…

Sadly, it quickly transpired that all was not well. Both the Pratts had passed over. Elva died on the 3rd of March 1990, aged 77. Anthony – nearly ten years her senior – outlived her by four years, passing over with Alzheimer’s on the 9th of April 1994. He died, aged 90, at The Oaks residential home in Bromsgrove, Birmingham. Perhaps this is where the idea arose that he died in penury? There’s no question that the money on which he’d missed out would’ve come in tremendously useful at that most difficult time.

Today, Anthony and Elva are both buried in the serenely beautiful grounds of Bromsgrove’s Old Cemetery. Their tombstones are a short distance apart, close to the outstretched, evergreen limbs of a stunning monkey puzzle tree. Daughter Marcia – a now-retired Birmingham civil servant – lived close by for many years – and saw fit to include Cluedo on her father’s epitaph.

–

To stay in the loop with the latest news, interviews and features from the world of toy and game design, sign up to our weekly newsletter here