Creative consultant Deej Johnson explains why new inventors should learn to love limits

Deej Johnson, co-author of The Snakes & Ladders of Creative Thinking, on why creativity needs limits

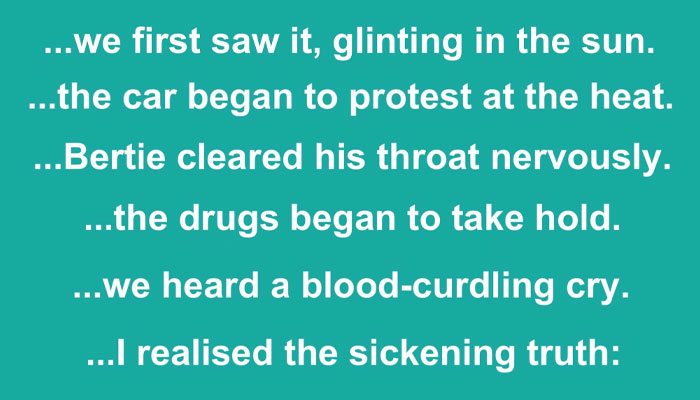

Want to see the colour drain from someone’s face? Ask them to start writing a story for you, right away. You can pretty much guarantee that – even if they have the ability to do it – they won’t relish the idea. It’s too big a concept; it’s too open… It could be a story about absolutely anyone doing absolutely anything. On top of that, it’s open ended: “Start writing a story.” Ugh!

It was a Dark and Stormy Night…

Present the exact same person with the start of one sentence, though, and ask them to finish just that in 30 seconds and you’ll probably get a different result. By way of example, take this sentence from Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

“We were somewhere around Barstow on the

edge of the desert when…”

How easily could you finish it? Here’s how I – and the writer Hunter S. Thompson – chose to end it:

Why’s This Important?

When given a limit – in this case, the start of a sentence – many people feel as if an unhelpful number of options have been eliminated. This example shows how limitations can actually impel creativity – not prevent it. Moving away from the written word, you might appreciate how limitations can help generate board game ideas because – infuriating though they can be – there MUST be limits to ALL creativity.

Creativity MUST Have Limits

It was put to me recently that a creative effort that has no limits is, by definition, art. In fact, though, even art has limits. It might be the size of the canvas, or the number of people contributing to a dance, for example. It might be an artist’s skill level in a particular medium! Elsewhere, it might be the amount of money in the development budget, or even – as with almost anything – the date by which a project must be ready.

Learn to Love Limits

The reason I mention this is because many new inventors seem to resent having limits imposed on their thinking… And yet I can’t think of many things that more clearly telegraph amateurishness than this attitude. I might go so far as to say that if an inventor can’t learn to love limits, they’re not cut out to be professionally creative.

Briefs

I say that because it’s tremendously unusual to start work on a paid project with absolutely no limitations. These limits might be presented up front in the form of a brief, or a wish list. I discuss this in more detail in a free toolkit available from www.mojo-nation.com/toolkit. Here, though, are some views on setting your own limits while creating board games…

Emotion vs. Logic

Of all the limits you can apply at the very start of a creative process, this is not only one of the most important but also one of the most-easily overlooked. Ask yourself this: how do you want players to feel when they play your game?

Please don’t just say you want them to have fun. Fun is a small, nebulous word that – in theory at least – applies to all games. Drop It is fun. Ninja Rush is fun. One Night Ultimate Werewolf is fun. You don’t experience the same emotions playing those three games, though; they elicit completely different feelings.

The reason that it can help to impose this limitation early on is that it both shapes and shifts ideas. By way of an example, let’s say you have an idea for a game based on a mathematical principle, like the picture-matching behemoth, Dobble…

In its current, fast-and-furious format – and with its logic behind it – Dobble creates frustration, hysteria and mild panic. Nevertheless, the same maths could easily create a tense, pensive, and slow-moving strategy game if that’s a limit you set. So consciously choosing the restriction of which emotional experience you’d like players to have can definitively shape a game.

Not Just Luck

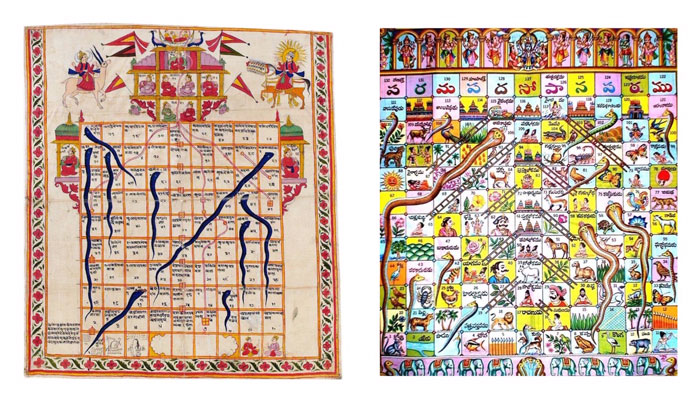

Originally based on an ancient Indian game called Moksha Patam, the basic idea of Snakes & Ladders used to have a little more to it. There were fewer ladders than snakes, and these things represented virtues and vices respectively. Dating back to at least 200AD, its race-to-the-end format was in perfunctory service to the game’s morality lessons. When Moksha Patam reached England in 1892, however, these lessons were given a Victorian-values makeover. It became a little less spiritual, and the number of snakes was made to match the ladders.

A further simplification occurred when Snakes & Ladders arrived in America, and the reptiles were deemed unappealing. The bitey little buggers became chutes – slides, as we call them in the UK – and the already-diluted moral aspect then morphed again… They became chore related, before vanishing completely from many versions. With every edition, however, it’s probably fair to say this…

Snakes & Ladders is awful! The only thing that determines a winner is the luck of the dice. And while this makes it an ideal way to teach young children about games, and the mechanics of dice, counting, winning and so on, it makes it interminable for most adults. What’s more, that’s likely to be true for most games in which the outcome depends purely on luck. While there are exceptions to the rule, including many ‘toyetic’ games like Pie Face, the degree to which players can influence the outcome of a game is a limitation you may want to consider.

Biggest Nose, Oldest Player, Player with the Smelliest Farts

Now that things like throwing a double six to start a game have – mercifully – fallen out of fashion, it feels like there’s a newer problem… It seems one of the easiest ways to add so-called novelty to a game’s start is to present what the inventor must fancy to be a wild-and-wacky rule. Sometimes this is at the cost of getting on with the game, and often it has absolutely nothing to do with the plot. Better, perhaps, to limit how long it takes to do something, be that start playing or – in more complex games – set up some of the components, deal the cards, etc.

Elimination and Miss a Turn

With modern attention spans being what they are, games in which you’re penalised by being forced to sit out for any period of time would seem a bit risky. Few games are sufficiently entertaining that they hold you absolutely mesmerised when it isn’t your turn. Add the prospect of missing your next turn altogether, and you have the ingredients for mind-numbing boredom. It feels to me as though miss a turn has mostly had its day.

Incidentally, there have been times when I’ve made the above point and been reminded of games that DO succeed despite having a miss-a-turn limit: Exploding Kittens and Rhino Hero come to mind. Well, in the first instance, there are, of course, exceptions to every rule. With both Exploding Kittens and Rhino Hero, though, missing a turn isn’t always punitive. In some cases, it’s a blessed relief: you’re out of danger! It’s also fair to say that, even if you’re not playing, both these games are considerable fun to watch. Which is my next point…

Is it Fun to Watch?

Since Pie Face showed the toy-and-game industry what social media can do, it seems the degree to which a game looks like fun outside a TV advert has become much more important. Obviously, it helps if a game can grab attention on a screen, in a pitch, and sitting on a shelf in store. It also helps, though, if it holds your attention when it’s not your turn. Depending on the type of game, making it fun to watch can be a helpful limit. Obviously, this is far less relevant with tabletop games since the time and attention one must invest when playing them is a given.

The ‘fun-to-watch’ point may also be less important if one of the restrictions you place on your ideas is that everyone must play at once, as with Happy Salmon, Dobble or Grabolo. When that’s not the case, though, it’s worth keeping in mind that, during many games with two or more players, it isn’t your turn for at least half the time. For that reason, you might want to think about applying limitations either to how long each turn lasts, or what emotions you experience while just watching.

Don’t Be a Donkey!

By way of example, are you familiar with the game Don’t Be a Donkey!? If you are, you may recognise that its mechanics are a smart restyling of the old card game, Spoons. Given that you can play Spoons for the price of a pack of cards, then, there have to be solid reasons to pony up for this donkey game – and there are…

The design is such that it’s neatly done away with the elimination element of Spoons, and replaced it with a daffy-looking penalty. If you fail to grab a small plastic carrot during each round, you incrementally adorn a donkey’s ears, nose and teeth. Like Shakespeare’s Bottom, the slowest player eventually turns into an ass. So you all play at once, no one gets knocked out and it’s fun to watch.

Toys with Rules

Paul Fish from Far Out Toys concisely sums up a restriction he imposes on game designers. He once told Billy Langsworthy, “The games we’re most interested in are what we call toys with rules.” As an example of the kind of limits one might place on a silly-social game, this is invaluable. Paul is effectively saying that he feels that the days when family games could have complex rules and little action are long gone. Playful things now need to happen – and happen quickly.

Market Limits

Billy also speaks of a scenario which illustrates this point rather well. Let’s imagine you’ve invented a game with a toy gun, one that shoots, say, a rubber bung 20′ further than the best Nerf shooter. You may feel that since this is arguably better than Nerf, you now have an idea that rivals that brand…

The limits of the market being what they are, though, strongly suggest that few toy companies would want to do battle with Nerf. Under the circumstances, you might be better off taking it to Hasbro and pitching it as a Nerf game – even if that meant losing 10′ of shooting distance because it needs to shoot foam.

That might sound like we’re suggesting you make huge compromises, or sell out to bigger business. That isn’t the point. The point is that if your idea needs backing, then it needs the confidence of others… And if it needs the confidence of others, then you may need to accept the limits others want to impose. Don’t think of that as intrinsically bad. The Nerf example is purely theoretical, by the way; there are some excellent reasons for not making a gun that shoots 20′ further than a Nerf. Some of these apply to Health and Safety which always requires limits – although that’s too big an area to deal with here.

Choose a Component/Mechanic

Have I ever met a designer who routinely creates games by dedicating themselves to the restrictions of a specific component or mechanic? Not that I recall. This isn’t to say that it can’t be done though: they’re just factors to nudge. Below are some components that make up board games; you can certainly set yourself a limit or goal based on any of theses elements:

• How many people can play?

• How do you actually win?

• Is it competitive or co-operative?

• How long does it take to play?

• Are there rounds, or is it one and done?

• What choices do players make?

• Does luck affect the outcome?

• In what way do people interact?

• What’s entertaining about it?

• Do any players get eliminated?

• Where are people going to play this?

• Do you take turns, or all play at once?

• What emotions do you experience?

• Is enough happening to hold attention?

You can ask very similar questions about which mechanics to use in tabletop games, too: Area Control, Card Drafting, Deck or Engine Building, Grid Movement, Hand Management, and so on… In terms of exploring this vast subject, a comprehensive guide now exists that sets out to explain them. Take a look at The Building Blocks of Tabletop Game Design: An Encyclopedia of Mechanisms by Geoffrey Engelstein & Isaac Shalev.

Alternatively, you can find some pretty handy lists when you type Board Game Mechanics into Google. All that said, it’s worth noting that reading up on, and answering these questions, is just one way to input useful information.

Adapted from The Snakes & Ladders of Creative Thinking

By Deej Johnson & Billy Langsworthy

—

To stay in the loop with the latest news, interviews and features from the world of toy and game design, sign up to our weekly newsletter here