From horror to honeypots: prolific game inventor and author Mary Danby on why she’s proud to be an I.D.I.O.T.

Thanks for doing this, Mary. When we interview people about their route into toy invention, some people say they loved toy design: it was always the plan. Others are doing other stuff, and it’s a bit more like a trap door: “I was doing this, then I did this…”

Oh, I’m a trap door then.

You’re a trap door! So how did you how did you find your way in?

Well, if I’m going to start at the beginning … I would say that, unlike lots of inventors, I don’t have any design or invention background – but it’s in the blood. My brother was a very successful inventor of intravenous pumps. And while my father, who was a vet, didn’t have much to do with our lives, I’ve discovered that he invented an anaesthetic mask for dogs that was used for 30 years.

Wow!

But I think perhaps the key to the whole thing is that I’m descended from Charles Dickens. And this is where getting into the toy business starts. It’s quite bizarre, really… I hated school – the only thing I was any good at was English. And when I left school, I took the train down to Hastings, threw my horrible straw hat in the sea and watched it bob off towards France. “That’s enough of that!”

No university? No A-levels?

No, nothing. I became a secretary, then spent about eight years in television production, which I loved. I got to work on all sorts of things – documentaries, sports programmes, some dramas. Latterly, it was for ABC Television in Teddington – it’s defunct now. But I absolutely loved working in television.

Why did you leave?

Well, they merged companies and offered quite a lot of money if you said you’d be redundant. So I took my money, went to work in the States for a while, came back – and didn’t know what to do. And then I met somebody who said, “Oh, you’re just the person Mark Collins wants.” And Mark Collins was the son of William Collins, the founder of Collins Publishers, which is now HarperCollins. They needed a fiction editor for their Fontana paperback imprint. I’d never been in a publishing office in my life but I somehow managed to get the job. And on my first day there, I met Mark in reception. He said, “Come upstairs and meet your secretary…” And I thought, ‘My WHAT?’

Ha!

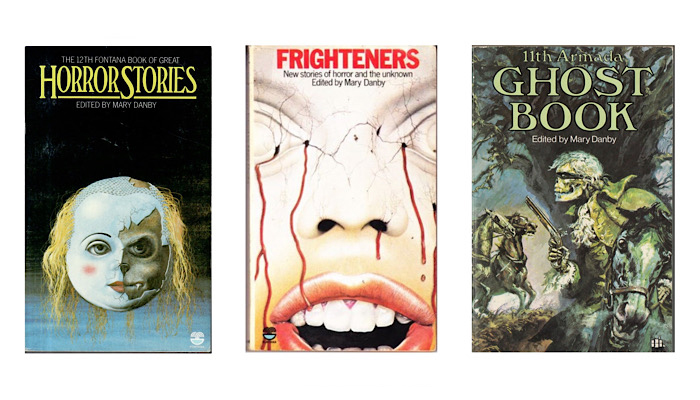

So my secretary really taught me how to do it. While I was there, I started writing. I’d always wanted to write, so I took over their series of horror stories as a compiler/editor. I did that for years and years. Then, in order to get myself published, I wrote some short stories myself to put in the books. They were pretty gruesome, scary stories.

I’m a massive horror fan, Mary, so I’m absolutely going to look for those!

It was a series called the Fontana Book of Great Horror Stories. And actually, somebody later compiled a book of my short stories. It’s called Party Pieces. I’ve always loved horror, but I don’t think I could write that sort of thing now – the real world seems to have overtaken fiction as far as horror is concerned. I also did some children’s ghost stories. In all, I wrote or compiled about 150 books and a couple of novels – all sorts of stuff – before I changed course yet again.

Amazing!

After I got married, I didn’t want to work full time because my husband was away such a lot. He was a BA pilot, and eventually became one of the first Concorde captains. So I was working from home doing all this writing… And then we had a daughter, and she used to sit on my study floor and play. One day, I was working on a book called Metal Mickey’s Boogie Book… Metal Mickey was a TV-series robot that lived in a house, and would wander around going “Boogie, boogie,” or something. I’m sorry, Billy, this is a very long story!

Noooooo, it’s great, it’s crazy… I love it. Metal Mickey’s Boogie Book…

So I’m working on Metal Mickey’s Boogie Book, and my daughter was playing with one of those magnetic theatres where you move the characters with a magnet on a stick. And I just happened to think that it was a very robotic movement. And I wondered if I could perhaps turn this into a robot game. And I had a game at the back of a cupboard, called Tell Me. Do you remember it?

Yes, the game with the spinner?

Right! So I got this Tell Me spinner and fitted it up with some elastic bands and magnets and put it under the stage of the theatre. I carved an old bit of balsa wood to make a robot that spun round and pointed at things you could pick up. But having done that, I didn’t know what to do with it… However, because I’d been doing Metal Mickey’s Boogie Book, I knew the character-licensing agent, a man called John Sinfield. I rang him and asked if anybody did Metal Mickey games. And he told me to go and see Ronnie Sampson at Invicta Plastics – they used to put out Mastermind.

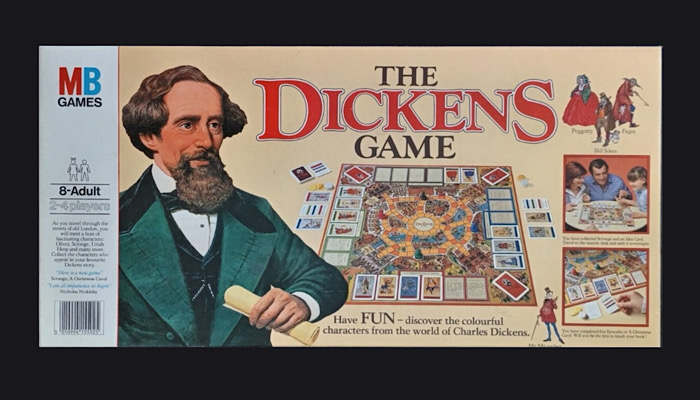

So! I went to see him – and that was my first visit to a toy fair. He was quite interested and said send it in. We soon got to talking about other ideas. At that time, I was also a consultant editor for Armada Children’s Paperbacks, and I happened to have their publishing list with me. He looked through that and said, “Dickens?! That would make a good game…” So I said, “Funny you should say that – he was my great-great-grandfather! Would you like me to invent a game about Dickens?” And Ronnie said yes.

This is amazing!

Well, I went away and created a board game. I’d always been a big fan of board games, so this was a labour of love. I sent it to Ronnie. And I was used to publishing, where you would get an answer within a few weeks – but months went by on this; months and months and months! And eventually I said, “Oh, look – just give it back!” Then I rang John Sinfield again, and asked what I should do. He told me to show it to a certain three people at toy fair, and to mention his name. And that’s the thing about the toy business: people are so kind and so helpful and not protective of their own stuff. They freely give their advice, don’t they?

Yes. 100%.

It’s wonderful… So then I took it to Waddingtons, and the man there liked it. I was so excited! The second one was Michael Stanfield but it wasn’t for him. The third company on my list I’d never heard of… It was called Milton Bradley… It later became Hasbro, of course, but in those days the really big name for games in the UK was Waddingtons. Anyway, I walked around the corner, and there’s the biggest stand in the whole toy fair. I met the sales director. When he saw the game, he thought it was interesting and said, “Send it in.” So I did – and they bloomin’ did it!

And what was the game? What was it called?

The Dickens Game. Sorry! That was a very long story – but that’s how I got into it. Also, when the game was with Milton Bradley, I met Howard Webster, who was one of their product designers. He turned out to be the brother of one of my husband’s best friends, so we got friendly. A bit further down the line, he left Milton Bradley and came to work with me. So we worked together for quite a few years.

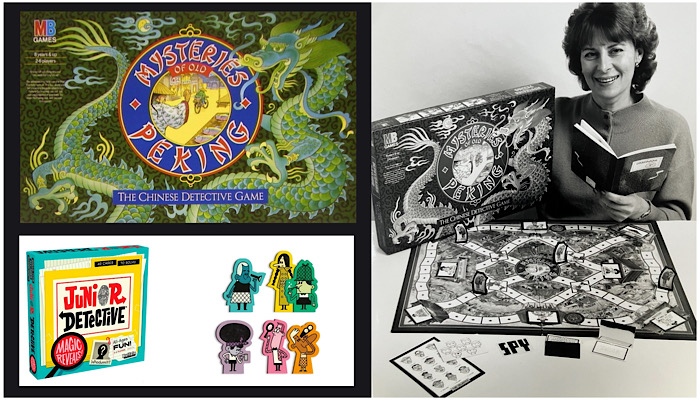

In the meantime, I experienced my first disappointment. The second game I sent them, they liked, but then dropped. And then I came up with a customisable game. It had different stickers you could put on the board and various puzzles to solve. One of the puzzles was the Mystery of the Chinese Necklace. You had to find these pearls, and – do you remember Roger Ford? Wonderful Roger Ford?

I didn’t know him personally, but I know the name.

He looked at this game with Mike Meyers, who was over from Milton Bradley in the States. And Roger said the setting I’d got for this mystery – ancient China – was the best thing. He told me to go away and forget all the customisable stuff. Just develop that theme. And I thought that was a fantastic opportunity –to be directed like that. Because as long as you follow people’s directions, they can’t hate what you do, can they?

I’m sure I could find a way! I’m just going to say that we spoke to Mike Myers about his career. People can read that here. And did you do it; did you focus on the mystery element?

Yes. I spent months on it… Months and months and months. I had a team of local children who’d come over every Saturday morning and play it and play it and play it and play it. When I took it back to Roger and Mike, I was so confident that I said, “You’d better buy this or somebody else will!” Well, they bought it on the spot – and it’s still going, 35 years later.

Amazing. And what’s that game called, Mary?

It’s called Mysteries of Old Peking, which is – I’m pleased to say – something of a classic in France. That’s always been its main market, but it’s sold about three and a half million copies worldwide. So it’s with Lansay as Les Mystères de Pékin, and now it’s with Buffalo in the States as Junior Detective.

Ah! We interviewed John Bell recently about that… I’ll link to that here. I didn’t realise that was Mysteries of Old Peking.

Yes, and it’s kind of its own brand in France these days… There are several versions of it: a junior version, a card-game version, an electronic version, and so on.

Wow. And at the time you first showed that, was inventing and pitching games a big part of what you were doing?

I carried on doing the writing as well. But Howard, who lived in Yorkshire at the time, would come down every few weeks for a couple of nights. We’d work on things together. And I couldn’t draw… This was long before you could do it all on the computer. We were barely out of typewriters. So if a game needed a logo, or a product drawing, I was a bit stuck. But Howard was fantastic. He taught me an awful lot about the toy business. The other person who was incredibly helpful was John Dixon…

From Dixon Manning?

Right. He was one of the early organisers of the Inventors’ Dinner. It was John who told me to come along to the event so I could meet people. And once you go to the Inventors’ Dinner, you’re recognised as a bona fide inventor. So you can then approach anybody and say, “Oh, I saw you at the dinner!” You know? You’re in. That was so valuable. And that’s why I’m so keen on it…

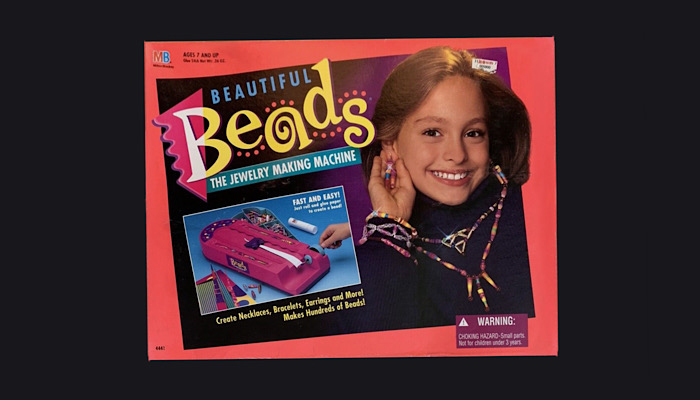

Anyway, just after Mysteries of Old Peking came out – and partly due to the different people who came to work with me – I started working on activities as well. I came up with this device for rolling paper beads. I made the prototype with a cotton reel and an elastic band, basically… I seem to be big on elastic bands! We sold it to Milton Bradley. It was called Bead Studio in the UK and Beautiful Beads in in the States. That sold around a couple of million, and the product is still on the market. Then we did another game for Milton Bradley, which was the Aladdin Magic Carpet Game.

With a flying carpet?

Right. That one was a case of our creating something without a brand in mind, and then a brand came along that perfectly fitted the idea. I think Howard had a niece who was very keen on doing art, and we talked about magic carpets. The niece wanted to do this amazing board, so I devised a mechanism for flying a magic carpet around it. Very lucky timing.

And your hide and seek game?

Pooh’s Hide and Seek Game, yes! For that one, it was just a drawing… Literally just a pencil sketch about rabbits on a bus. Parker Brothers turned it into a game with characters popping out of honeypots. Again, that was a huge seller. And that’s amazing, when you happen to match an idea to a brand in that way, because you just get lucky sometimes… So much of it is luck, isn’t it?

Absolutely. And is there any game of yours that you look at, Mary, and think of as being your most underrated?

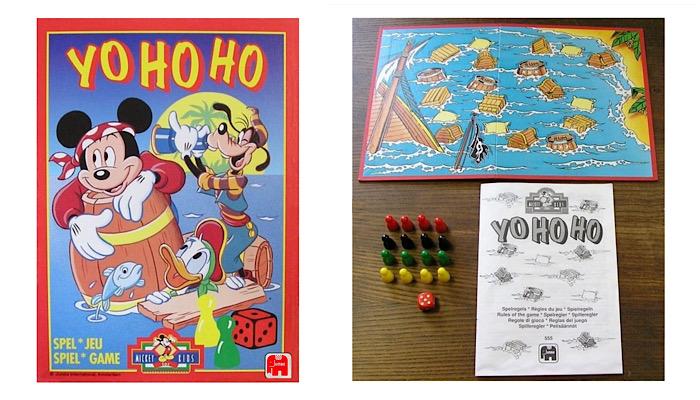

There is, because it’s one I play with my grandchildren all the time. It’s their favourite game; it’s called Yo Ho Ho. A long time ago, Milton Bradley used to do what were known as ‘10 Deutschmark games’: little boxed games. I created it for that range. It’s really simple; just a roll and move game, but with big potential for being beastly to other players. Jumbo then did it as Mickey’s Yo Ho Ho, but I’ve never found anybody to do it since – hint!

Ha! And in terms of how you came to work with Carterbench… How did that happen?

That came through the Inventors’ Dinner, because Rob Kay – Carterbench’s MD – was on the committee at the time. In those days, the committee used to come down to my cottage in Berkshire in the summer for a lunch-in-the-garden meeting. Just an excuse, really.

We have to bring that back…

Welcome to! But I got to know Rob that way, and he thought it would be good to have a team down south – so we became Carterbench South. That way, if inventors in my part of the country wanted to work with Carterbench, they’d come and see me, and we would also go up to Macclesfield to work on projects with Suzanne Robinson and the rest of the Carterbench gang. The thing is, you never know where things are going to come from next, or what doors are going to open – and I hope they don’t ever shut. I love to wake up in the morning and think, ‘What have I got to do today? Oh, YES!’

I hear you. And everyone’s creative process is different in terms of how they have ideas… What sparks yours?

Working with other people. You’ve always got to have sounding boards. So eventually there were three of us: Nicky Wastie, Lynn Ash – now Lynn Middleton – and me. We were a trio, working together for at least 30 years. We know each other inside out. We’ve got a sort of shorthand… I think it’s fantastic working with people who know where you’re coming from and who know the business. I find not having to explain anything really liberating… Over time, we focussed as much on crafts as games, and Charlie Bason joined us for a number of years. Nicky – who is immensely creative on the activities front – and I are still working on lots of things.

And in your experience, what makes someone good at inventor relations at a company?

Oh, I don’t know! I knew you were going to ask me these questions, Billy! I don’t have any advice for anybody or anything like that… But one of the lovely things about this industry is that the people you meet tend to become friends for years, and I think it’s the friendly ones… You know, when you feel pleased that you’ve got a meeting with so and so. Because you know they’re going to say hello and sincerely ask, “How are you?” and make you feel like a person… And it’s just a pleasure to see them regardless of the outcome.

Incidentally, the best piece of advice ever given to me by a product picker came from Chris Campbell at Parker Brothers. He said the best inventors are tailors… “You want a bit off the sleeves? Certainly, sir.” “Some frou-frou around the hem? Of course, madam. No problem.” He was so right. Flexibility is key.

Great answer. And are there any key evolutions you’d point to, Mary? Things that show how the industry is different now in terms of how you pitch or develop ideas, say?

Well, I think one of the problems now is that everybody – except old people like me – is trained in video and graphics and CAD to a far greater degree. I mean, I do videos just because I like doing them… And I can do basic graphics –but I’ve had to teach myself. There was no such thing when I when I was starting out. And I can’t even draw! I mean, I can convey an idea, but I’m not an artist. Younger people are used to doing things properly. I can’t get away with what I used to!

Fascinating. And diving back into the Inventors’ Dinner, I’m interested: what was your first impression of that event?

Oh, everybody was so friendly! It was so easy to meet people and to have people say, “Oh, come and pitch to me!” – stuff like that. And because it’s an evening thing, and it’s kind of unofficial in its way, people don’t have to be too corporate, as it were.

And did you ever think it would still be going nearly 40 years later?

No! I mean, I joined the committee when Chris Taylor was mostly running it with John Dixon. They ran out of steam a little and stopped having it at a different venue every year, so we ended up in the Copthorne Tara Hotel in Kensington, which was a sort of, um, an underground dungeon. It was a really uninspiring place. And it was clear that the numbers were going to drop off because – well, who wants to do that every year? So when Chris and John said something about other people taking it on, Rob Kay looked at me and said, “Shall we?”

You know, I’ve just realised you’ve mentioned a lot of names and I need to flag some links! So people can read about Chris Taylor, John Dixon and Rob Kay here, here, and here! Sorry, Mary.

No, not at all. Anyway, from there, more people came and went. And it was brilliant. And now you’re doing it so fantastically, Billy. I’m really pleased because I can see it going on and on. And I don’t think it’s lost any of its spark.

Well, it’s easy to run with such supportive people in the room. And actually, the I.D.I.O.T. Award – given out at the Inventors’ Dinner is a good example of that… There’re lots of other industries where an award win is a great thing for some people and a bad thing for others, or it can be a bit “meh”! But I don’t think anyone’s ever been anything less than overwhelmed with support for the I.D.I.O.T. Was that true for you?

Oh, no; not at all. Mine was complete rubbish!

Ha! How so?

I’d only been to a couple of the dinners at that point. Honestly, I think they must’ve been wondering whom they could give it to. And maybe they thought it would be a good idea to give it to a woman back then. I was very new to the toy business, and I’d had a really nice meeting with Phil Orbanes that morning. I think he was with Parker Brothers at the time. Either way, he was presenting the award, and I think it was given to me just because we’d had a good meeting.

Oh, I’m sure you’re downplaying it. In any case, with the amount of products you’ve done now, you’ve earned it in retrospect!

Oh, you’re very nice! I’ve probably licensed about 150 products now – and I am very proud to be an I.D.I.O.T.

Of which, with some of the I.D.I.O.T. interviews, we’ve spoken to friends and colleagues of winners who’ve passed away, sadly. And again, I’m going to put links in so I’ll say ‘here’ a lot… We’ve had Fleur Tisdale talk about Simon Holdsworth here; Richard Wells spoke about Richard Pain here; Bob Fuhrer spoke about Michael Lyden here. There are more to come… But it’s amazing how enthusiastic and passionate people are; they really light up…

I think people actually love them. You know, there are people on that list that I think of with enormous affection… People who’ve been kind and helpful and done their absolute best to help you as an inventor.

Right. And Jonathan Becker talked about his dad, Jim here. Also, we shared a piece on Stan Clutton that Ron Dubren did here, and…

Oh, Stan… He was just MAGIC!

Well, we’ve never had a reaction like it to a post on LinkedIn. It was remarkable.

He was a lovely man. It’s the only way you can describe him. You know, you had to meet him. He always greeted you with a big smile and such enthusiasm, and I didn’t know him away from toy stuff. But Stan was just lovely.

Well look, thank you for doing this, Mary. Honestly, it’s been fascinating… It’s so interesting to learn that Charles Dickens was your great-great-grandfather and that a huge coincidence over that helped you get your start in the industry. Amazing! Is there a Dickens brand? Someone who looks after the Dickens licence?

Nooooo, no. Because it’s out of copyright. Anybody can do anything with it. The Dickens family is the most amazing organisation, though. We all know each other; there are hundreds of us! Actually, we’re currently organising an outing to the new Oliver! musical next Easter. And so far, I think 70 of us have signed up for it! But you know, being descended from Dickens means nobody ever thinks it’s odd if you achieve something. In most families, if you wrote a book, say, there’d be a bit of a fuss… “You’ve written a book? How marvellous!” With us it’s, “Okay… So what else is new?”

Ha!

So yes, my aunt was a best-selling novelist, and several people in the family have written books. And being related to Dickens does help when it comes to the publicity because it gives people something to hang it on.

Amazing. Maybe I’ll put it in our headline! Thank you, Mary. Brilliant.

–

To stay in the loop with the latest news, interviews and features from the world of toy and game design, sign up to our weekly newsletter here