Game designer Rikki Tahta on the importance of boiling concepts down to their essence

Rikki, thanks for making time. Let’s start at the beginning – how did you find your way into game design?

I run a software business with a partner and was a banker for a while, but I’ve always made games on the side because I love games! I self-published them because I could – and it was fun – and it grew out of that. But I still only do it as a hobby.

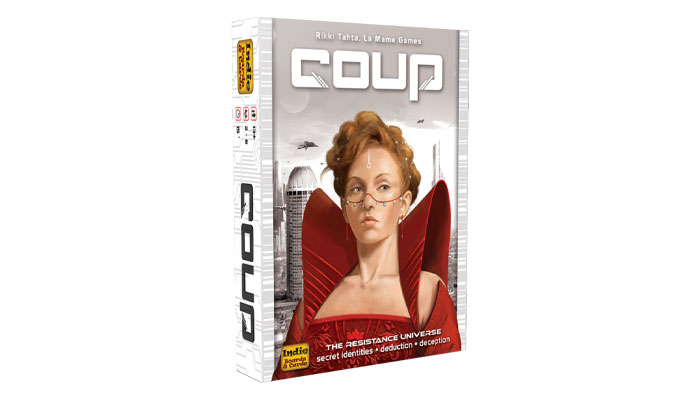

And while it remains a hobby, you’ve created some beloved titles. Am I right in thinking Coup was your first big success?

Yes it was. I created Coup because I like poker. I used to have a regular poker game with my finance buddies in New York. We’d play for tiny stakes, and it was really about the bragging rights and the trash talk if you lost that motivated us to take it seriously, and that’s the thing I don’t like about poker… The money! I don’t particularly like winning money off people, and I certainly don’t like losing money, but for most people the money element creates the stake and the fear of losing. Without that fear the bluffing in poker loses meaning.

Also, the interesting moments in poker only happen every five or six hands. If you’re playing efficiently a lot of the time you’re folding. With all that in mind, I spent time creating a game that distils the bluff element, with a stake, but without money – and taking away the boring bits from poker. I noodled around and came out with Coup, but games take me a long time to make.

Oh really?

On average, each of my games take about three years to make. Coup took around five or six years – and that sounds a bit strange considering how simple it is.

What takes time in your process?

Well, I noodle and noodle away, stripping out all the extraneous rules. I try to boil games down to their essence – and sometimes you can boil away too much and it’s no longer fun or interesting. There’s plenty of concepts sitting on my shelf that haven’t quite made it because I haven’t been able to distil them down into something that’s simple and still fun.

And did you self-publish Coup initially?

Yes, I self-published Coup, my family packed it into boxes and we took it to Essen and people really liked it. Now, every year we go to Essen as a family and launch a new game. We always self-publish until a publisher comes along and wants to pick it up.

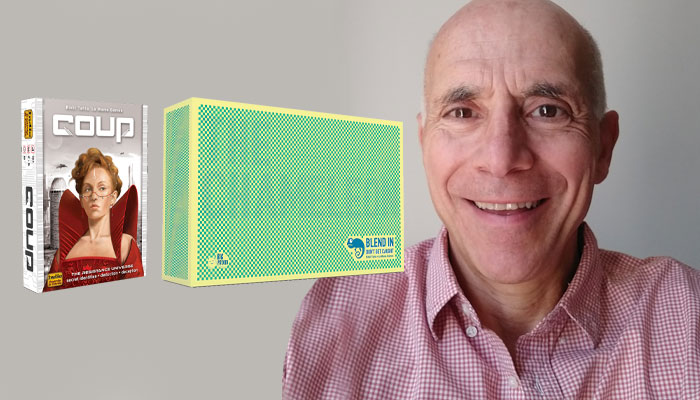

Did your self-published version of Coup differ much the version that Indie Boards & Cards published?

Our original one was set in a medieval city state because I needed a backstory that fit the mechanics of the game. My brother-in-law is an illustrator, so he did all the wood-cut style imagery in the style of Holbein. Then Indie wanted to do something much more commercial with it so they put it in a sci-fi world. That’s how most of my games work… I do some weird, wacky theme and then other people commercialise it.

It was the same with the expansion for Coup. My one was set in the Guatemalan revolution of 1954 – an extraordinary time in the country’s history. That was totally not going to fly with a US audience because in Central America in 1954, the US were the big baddies!

Understood! One interesting thing with Coup is that you don’t have to be great at bluffing to get by in that game. Was that part of the thinking when you were designing it?

Yes, you can just play it straight – my dad was like that. He never lied! But then he didn’t win very often. The optimum strategy is to bluff somewhere between 25% and 33% of the time. You want to be telling the truth more often than lying, but you need to lie occasionally to maintain a level of uncertainty. Look at poker, it’s a matter of assessing probabilities and the consequent risks and rewards, but does require some expertise in mathematics. With Coup, I wanted to combine a simpler assessment of probabilities – that anyone could do on the fly – with social deduction.

Is there any rhyme or reason to the sorts of games you find yourself designing?

I create games that I like to play; it’s not commercially driven in that sense. I make games that I want to play because I have the luxury of not doing this for a living; it’s a passion. I argue very hard with publishers sometimes about things like rule changes… Sometimes I’d rather they don’t publish it than make certain changes. But to answer your question, I create a mix of games but they all tend to be social and interactive.

I also tend to like shorter games with simple rules. I’m in awe of genius designers like Martin Wallace who can meld theme and simulation so well, but that’s not me. I don’t have the patience to develop those deeper, longer, more strategic games.

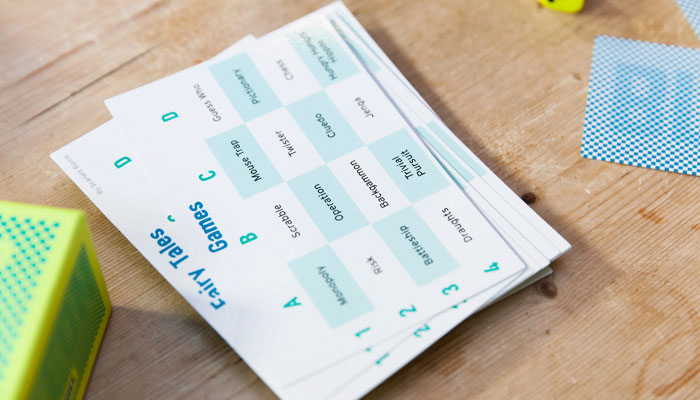

Speaking of social games, that brings us nicely to The Chameleon, published by Big Potato. How did this concept come about?

A bunch of influences went into Coup and the same is true of The Chameleon. The three big ones that went into The Chameleon were A Fake Artist Goes to New York, Spyfall and Codenames. They’re all great games, but I found flaws in all of them that could be helped by melding them all together.

What were the flaws?

In Spyfall, you have stacks and stacks of cards which meant there was a lot of preparation required. With Codenames, you have this wonderful idea around a one-word reference, but people would spend five minutes thinking of something only to come out with a rubbish clue like ‘Fire. One.’ In Fake Artist Goes to New York, there were the usual issues that come up with traitor games… But I love all three games and they all went into creating The Chameleon.

And before it found a home with Big Potato, did you go down the self-publishing route with The Chameleon too?

Yes, like all my other games we took it to Essen where it was originally called Gooseberry. The ridiculous thing about self-publishing is that the most expensive thing is the box. As an experiment, we sold the game without the box for €8, or with the box for €13. Everyone bought it with the box! I’d say: “Save yourself €5, here’s the same game in a plastic bag, stuff it inside another game box.” It didn’t work; everyone bought it with the box.

This links to what Big Potato is fantastic at. They took my game – which looked pretty pedestrian – and they made it look beautiful. It looks like a present! That whole experience made me realise that there’s a huge value in the aesthetics of games and the design of the packaging.

Linking to that, when it comes to your game finding a home, what do you look for in a publisher?

It’s a good question. I’d say a publisher that delivers what they said they were going to deliver. One that’s honest and keeps the lines of communication going. I want them to produce a lovely, quality item. How successful they are with it is less of an issue for me because I’m doing this out of passion rather than to pay my bills.

We’ve spoken about Coup and The Chameleon, but what would you say is your most underrated game?

I think my best game is Melee. It’s the one I’m most proud of – and it absolutely bombed commercially. Part of it was due to the artwork. I was persuaded by the publisher to go with this kind of cartoony, jokey artwork and it just doesn’t suit the game.

I love strategic, planning-based war games, and Melee front ends the planning part. You spent 15 minutes planning your campaign, and then it only takes 15 minutes to all play out. There’s a bit of bluff in there too as it forces some social interaction. There are some people who love it and recognise what I was trying to do, but most people wanted more game play for the investment in upfront planning.

Rikki, I have one last question – what helps you have ideas?

I like to riff on mechanics. It all starts with mechanics, the player experience, and the emotion I want to create. I also carry a notebook around and am forever jotting down ideas and testing little scenarios. That’s the advantage of creating simple games; it’s easy to iterate.

Huge thanks again Rikki; this has been fun!

–

To stay in the loop with the latest news, interviews and features from the world of toy and game design, sign up to our weekly newsletter here