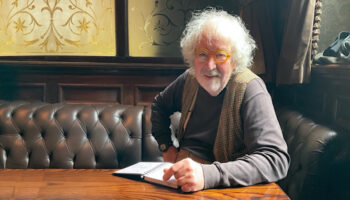

“Games fail in the face of reality – or they assert themselves!”: Zoch’s Walter Scholz on embracing unique ideas

Hi Walter, it’s great to connect. To kick us off, how did you find your way into the board game industry? Was it always part of the plan?

To be honest, I had no real plan of my future. When I was a student, friends sometimes brought games to our shared flat. It was a pleasant reminder that I had actually quite enjoyed playing board games as a child and teenager. Then I developed an own game together with a friend – rather amateurishly, but with a lot of passion! And then I thought about the fact that there must be people in publishing houses who make sure that interesting game ideas find their way to people who are happy to unpack and try them out… Then I did an internship at Ravensburger and started regularly visiting the SPIEL in Essen. And that’s how it gradually got to me…

You’ve been at Zoch for close to 30 years. What is it about the company that has kept you happily there for so long?

Well, it’s Zoch… Once I joined, I fell in love – and that just hasn’t changed. I like doing things which are a bit different and still adequate for a lot of people.

For any game designers that haven’t pitched to you before, what things interest you and Zoch?

Combine mechanisms. Change things a bit around. Try to be unique. Games fail in the face of reality – or they assert themselves. It seems important to me that the games challenge their target groups, but do not overtax them. It’s good when a game offers something unique. It’s bad if it doesn’t seem unique to the players.

I’d love to get your thoughts on what makes something ‘mass market’. I look at something like Zoch’s Piazza Rabazza – fantastic game! – and think it’s toyetic, it’s playful… To me, it’s a mass market game in both a European sense and a US sense. Do you think the lines are blurring between the two, or do you see them as very different beasts?

With strong physical effects, games tend to become a “gimmick”. This usually makes for entertainment on a visually amusing but somewhat “mindless” level… Which is not to say that good games should always be “witty”, whatever that means!

At Zoch, we try to unite the function with the game mechanism. In doing so, we remove – as far as possible – the “pure showmanship” from the function and, at the same time, we remove – as far as possible – the abstract, theorising “dust” from the game mechanism. This is at least our wish and aspiration. Of course, this doesn’t always work. Perhaps this claim can explain why we live in the “European niche” and at the same time know how to cater to American mass market tastes.

Terrific answer! Thank you. Now, can you recall the first game you licensed from a designer for Zoch? What made it a ‘yes!’?

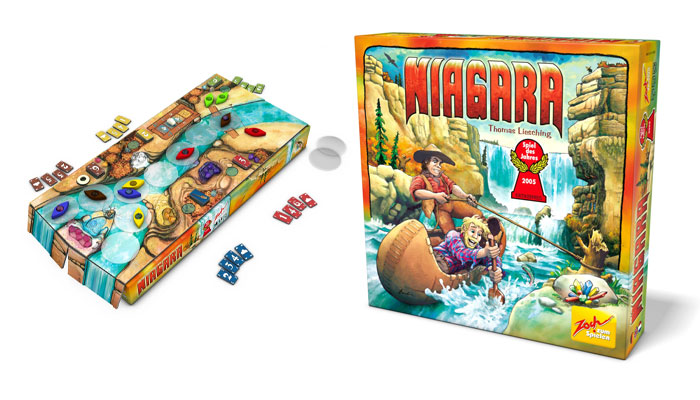

The first one I got on my own desk was Niagara from Thomas Liesching. It was a fantastic 3D prototype! I asked the designer: “Great idea, but why do the boats cross the river? Why don’t they try to fight the current of the water head-on?” Then Thomas and our team started to play – what we call – “development ping pong” and the game became, hopefully, better and better… At least it won the Spiel des Jahres award in 2005! But it was a “YES” right from the beginning because this one was extraordinary and unique.

A Spiel des Jahres winner right out of the gate! Good start! Some people in inventor relations tell us of the importance of ‘squinting’ to see where an idea could go, instead of focusing solely on what’s being presented. Is that true for you?

If the core of an idea convinces us, we always ask whether the “flesh” and the skin do justice to the great idea. The aim is to preserve the idea and polish it as much as possible like a precious stone by developing everything about the game so that “it fits”. You can fail at that. But we are always ‘squinting’ in this direction.

You’ve licensed titles from world-renowned designers, as well as brand new game creators. Why is it important for you to see concepts from designers of all different experience levels?

To be honest, I do not care for names as long as the ideas are interesting. Of course, it is sometimes easier – or occasionally more difficult – when you can rely on the complete professionalism of “old hands”. But in the end, it’s always the idea of the game and what we can or want to do with it that counts.

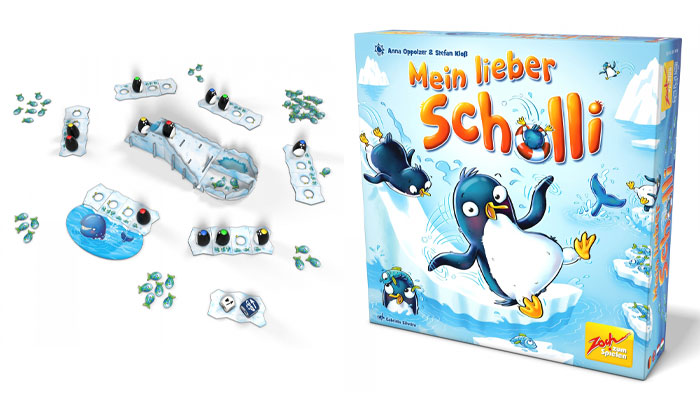

Let’s dive into some recent launches. Mein Lieber Scholli looked like a lot of fun at Spielwarenmesse. It comes from Anna Oppolzer and Stefan Kloß. What made this one a winner for you?

It’s again the combination of 3D effects – the slide – on the one hand and a well “narrated” game mechanism with nice rules. There are many small, novel elements – such as the whale – which makes the playing fields disappear and, by rolling the dice, turns into the coveted school of fish that the children want on the floe of their penguins. This is very charmingly thought out and is great fun for children… Not only but also because of the slide.

Great stuff. Mirakel Mix from Leo Colovini and Teodoro Mitidieri is another one that stood out at the show . It looks beautiful component-wise, and that’s backed up by a brilliant game! What appealed about this concept? And did it always have that brilliant turning cauldron?

Yes, the rotating magic cauldron has always been the centrepiece of the game idea. And it has always been linked to the idea that the mixture in the cauldron influences the probabilities that play a role in the game. This is cleverly “mathematical” without the players having to waste a thought on the “grey theory behind it”. They can instead devote themselves entirely to the fun of mixing potions.

This is the typical “Zoch twist” again: the effect is fun and the game rules sew everything into arcs of suspense; into playful challenges that are tailor-made for it. And, to pick up on a previous question, Leo Colovini and his team are truly brilliant professionals when it comes to harmonising game systems with publishers’ wishes. Originally, the game was about brewing beer, in a very grown-up way. Leo Colovini and Teodoro Mitidieri have very skilfully breathed family lightness into the game because we didn’t want a strategy game, but a family game, from this beautiful cauldron mechanism.

Walter, I could chat for hours but we have to wrap up – so, last few questions! What do you think is Zoch’s most underrated game?

As an editor, I often feel like a kind of “non-biological father” to children; I’m emotionally very close to the games. That’s why it’s almost impossible for me to answer which of these countless “hidden gems” particularly deserves to be more noticed – but that’s not how the world of games is.

With 2,000 new releases every year, there are now definitely more hidden gems than perceived highlights. That’s why I’m not highlighting any games and will leave it to the interested readers themselves to rummage through the Zoch program from the last 25 years if they actually feel like looking for gems. Because if you don’t look for your gemstones yourself, you will only come across finds that others have discovered as gemstones for themselves!

Good answer! Last one: How do you fuel your creativity? What helps you have ideas?

To put it heretically, I could put it this way: I’m just an editor… I don’t need ideas because the game creators have them. And even though I know that’s only partially true, I’m just going to hide behind that last answer in this interview. The second answer that comes to mind comes from John Lennon and Paul McCartney: “All you need is love.”

Lovely place to end things! Huge thanks again Walter.

–

To stay in the loop with the latest news, interviews and features from the world of toy and game design, sign up to our weekly newsletter here