GO’s Phil Neal on why he welcomes a little creative chaos in the invention process

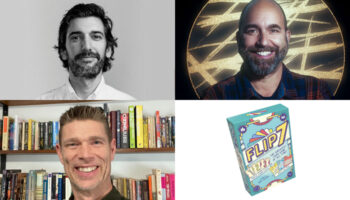

A toy inventor for over 25 years, Phil Neal is the creative powerhouse behind Go – a renowned invention firm with a strong emphasis on strategic collaborations.

Phil has a raft of success stories under his belt across the mass market worlds of toys and games, as well as the As-Seen-On-TV space, with inventions including Fisher-Price’s Shake n Go Racers, Stompeez, Flipeez, Hoverball and one of Alpha’s big launches for 2020: UZoom Racers.

We caught up with Phil to learn more about his beginnings in the industry and how he approaches invention.

Hi Phil, so to kick us off, how did you get started in the world of toy and game design?

Hi Billy. Thanks for asking. My college degree was in journalism, supplemented with a wide range of liberal arts studies. I was also an avid photographer as a teenager, and spent countless hours in the darkroom. So lots of areas of interest, but not one product design class. Everything I’ve learned about design, engineering and product development has been self-taught and through osmosis over the years. And the education continues…

My career path started professionally for five years as a madman in advertising at Ketchum and Saatchi & Saatchi. After that, I worked for a few years with a consultancy that helped amateur inventors with their ideas. That was followed by a few years at Machina working for professional inventor and “tech-futurist” Ralph Osterhout.

I then spent five years at KID (of Bop-it fame) with Dan Klitsner’s team, before venturing out on my own with GO in 2001. My first NY Toy Fair was in 1993, and I’ve been in the toy invention mix ever since.

How would you sum up your approach to design? And has it changed much over the years?

From my perspective, the best toy designs illuminate the primary features of the idea. And importantly, minimize any extraneous features that add cost, and may distract from the primary ‘wow’. Less is more; and because pennies matter with toys, the design process is necessarily a reductive exercise – how minimal can we make the idea, and still deliver enough ‘wow’?

Process-wise, I’m a big believer in a healthy bit of chaos in the innovation process. Given that our toy company partners see several thousand ideas a year, it’s just not very likely that we will find a blind-spot. And even if we do, it’s just as unlikely that it will be something that fits their plans. Quite long odds! So I think stirring the pot and mixing things up in search of unexpected connections is a helpful strategy.

Also, we try to resist discarding a “bad” idea out of hand (it’s hard not to do) because it’s usually the second, third or even fourth idea that follows that initial “bad” idea where we run into the winning idea.

I’m also a big believer in quick prototype studies to get our hands on an idea in 3D early in the process. Don’t overthink it. Just bang it out. Nothing like a glue-and-spit model for early validation.

That’s been the basic approach for a long time now. We are always on the hunt for ideas that will inspire a child to laugh, play, interact, grow and engage. It’s helpful to think (and act) like a kid. I think my girls and wife would say I’m the least mature person in our household. I quite like that.

Like most of my inventor friends, we have legions of unsold ideas. And, the ones that have been licensed over the years just happened to be the right idea, in the right form, on the right day, to the right customer. Simple, right? That’s the serendipity of our business, and that hasn’t changed much in over 25 years.

And if we look back over those 25 years, one of your most successful items has been the Fisher-Price Shake n Go Cars. Can you talk us through how that idea came about?

Shake n Go is a good example of a failed concept leading us to an insight and idea that happened to work really well with pre-school boys. The insight we stumbled onto was the illogical connection between shaking and powering up a toy vehicle.

My partner on that one was Scott Eckerman, and we had been kicking around the notion of powering up a car using the Faraday effect (eg no batteries, and generating power similar to how a Forever Flashlight works). That was a failed experiment, but once we were on the path of a solution that tied “shaking” to “powering a vehicle”, the concept came together rather quickly. Mostly because, once we added batteries, we were able to do a number of things using a microprocessor in the execution that completed the format and play experience.

Principally, we tied direct audio feedback and correlational input/output into the UI (using the shake feature and not just pressing buttons). We then partnered with a talented electrical engineer to build the first prototype. The prototype tested really well in Fisher-Price’s playlab, and the deal came together pretty quickly after that.

It also happened to come through the door at the right moment when Fisher-Price was on the hunt for a new pre-school vehicle line. And the last bit of luck for us was that Fisher Price had a supremely talented and dedicated team that made the brand even better than we could have imagined, and sold it worldwide for many years.

And while we’re on the subject of shaking, what’s been the biggest thing to shake-up the industry since you’ve been in it, and how did you react to cope with that change?

One thing I did strategically in recent years was to balance my product portfolio with direct response. I was introduced to the As-Seen-On-TV business by my friend Paul Von Mohr with our Stompeez brand. We followed that with the Flipeez, Hoverball and DreamTents brands. And, while it may sound hyperbolic, each of those four programs sold millions of units globally.

I’ve learned that if you have the right item in direct response, those licensees can drive significant volume. And while that category has its own challenges and headaches for inventors, we’ve been fortunate to have come out on top more often than not to date.

Regarding the toy industry, there is no doubt that there are legitimate challenges facing our toy manufacturing partners: the outsized influence of mass retailers, SKU reductions, Asia manufacturing woes, increased margin pressures, tariff nonsense, over-reliance on entertainment properties, video games(!), digital-age parenting etc etc etc. That’s all noise to me.

The reality is that as inventors, we are still in a fashion business. And, it’s a unique vocation in that we can still wake up tomorrow with an idea that just might be the next big thing for the next generation of kids.

There are always new kids. And there are still willing licensees. That hasn’t changed. If anything, there is often too much innovation focused on too few categories year-to-year (e.g an overabundance of collectables at the moment). I’m always pleasantly surprised when we come up with yet another new idea that we like, and that we think is fun and funny… and that we can’t wait to share with our toy company partners. I do love that about my job.

What do you do to fuel your creativity?

Stimulation of all sorts. I like mashing up unlikely, seemingly unrelated things. And like I said, we try not to get too organized or serious about any of it. In my experience, the best ideas have often come out of miscommunications that lead us to unlikely connections – it’s a funny business we’re in!

And I personally fuel creativity by reading fiction, travelling to new places, seeing live music, bantering and hanging out with my family, playing guitar, watching movies and TV, playing tennis, mountain biking and watching sports. And a good meal and an IPA (or a big red) with friends. It all feeds the process and feeds the soul.

GO is a one person company, so how do you make that work?

From the beginning, my studio has been structured on the premise that we collaborate with other individuals and companies on a project by project basis.

From my perspective, the idea of inventing in a vacuum is a myth. It is a process that requires generosity and really good listening through collaboration in order to find “the new”. It takes a village and more.

On division of labor, I typically co-invent and manage the marketing, legal and business aspects of the exercise. Every project and every partnership is different. We share in the risk and share in the reward. And sharing in successes are the best reward.

It’s been a successful model, keeps things interesting and provides me with some flexibility to match projects and ideas with different people. And I’m happy to say that I work with a lot of interesting people that are way more talented than me. I think there’s some wisdom in that approach.

What advice would you give to an inventor new to the industry looking to license their first concept?

First piece of advice is to keep your burn rate way down.

The pressure of having too much overhead at the beginning is a typical entrepreneurial mistake, particularly in the highly unpredictable world of invention and licensing. You should take the pressure off of having to invent something great by minimizing the finances going out every month at the start. It is really a challenge for someone in our business who is speculating on selling an idea for some future, nebulous reward.

And even if, and when, you do land those first deals, any significant royalty revenue stream will likely be a couple years out. So buy yourself time by keeping expenses down and take some contract work to pay the bills. That said, the (obvious?) downside of too much fee work is that there is an opportunity cost to having distractions away from working on new ideas. So it’s a balance.

The other thing I’d say is that I do believe is that we all make our luck, so treating others with respect and making an honest effort to do right by people will, in the vast majority of cases, be rewarded. And because there is a good degree of serendipity to every deal, it takes more than a little resilience and persistence to keep after it. Those of us that have survived and thrived over time, probably share the common qualities of resilience and persistence in our make-up.

And I like Edison’s quote: “to have a great idea, have a lot of them”. Being prolific helps for sure. All of it can be dispiriting at times, and we still have to be a little bit smarter than our brilliant inventor competitors and somehow surprise our highly selective and equally brilliant toy customer partners. But there is always a need for the next new and fun idea, every year.

Absolutely. Thanks Phil!

—–

To stay in the loop with the latest news, interviews and features from the world of toy and game design, sign up to our weekly newsletter here