Jacob Jaskov on bringing something totally unique to the tabletop in Fog of Love

“A tour de force.” “Unlike anything else on the tabletop.” “The best board game of 2017.”

These are just some of the many plaudits thrown the way of Jacob Jaskov’s Fog of Love – a romantic comedy in the form of a board game.

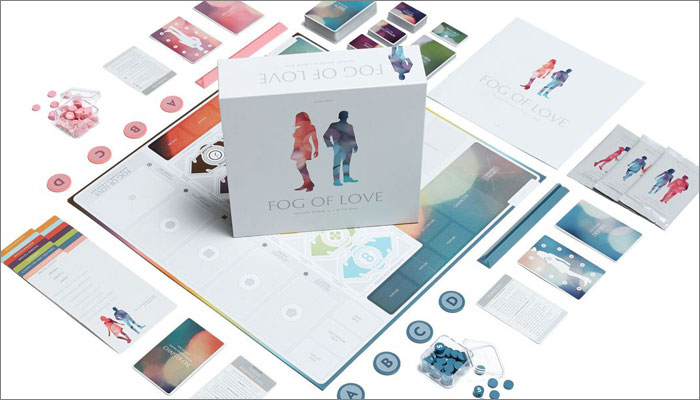

Created as a game that Jaskov could play with his wife, Fog of Love is grounded in storytelling and sees two players step into the shoes of a couple, complete with their own traits, features, occupations and hidden personal goals.

Players then have to navigate through a series of scenarios – an argument at a restaurant, a friend’s wedding, couples therapy – each with choices to make, with matching decisions or unfortunate disagreements steering the fate of the relationship.

Fog of Love has been hailed as a breath of fresh air to the tabletop scene; something totally different from the rest of the market. And when you look at designer Jacob Jaskov’s history as a pioneer in the world of innovation, it’s no surprise.

Amongst other things, he set up Denmark’s first focused initiative on how to drive innovative work and methodology, and was the content leader of and architect behind Laboranova, one of the world’s largest research projects on front end innovation.

We caught up with Jaskov to find out more about the design process behind Fog of Love, the trouble he had with publishers and his plans to make this the first in a trilogy of games set at different stages in a couple’s life.

What’s your background in the world of game design?

When I was young, I was a big games geek, especially when it came to role-playing games. We have a convention here called Fastaval. It’s really good and some of the leading role-playing game designers come regularly to Denmark for this event. I attended the event regularly in the Nineties and learned a lot about how to create stories in a new way, and not to focus too much on systems. Most RPGs focus on simulating combat and skills, but Fastaval is about looking at what drives a good story. So my background has a heavy focus on story-driven games and innovative ways of creating narratives.

In the late Nineties I was one of the most active people in Denmark in this space. I was arranging some of Denmark’s largest conventions and made some quite innovative scenarios, but it took up all of my life. I wanted to be something else other than just a geek! So I stopped. I wanted to be a futurist. I swapped studying philosophy and instead took up political science. I moved from Odense to Copenhagen and when I moved, I didn’t play anymore because I wanted to change my lifestyle.

I then got a research assistant job at the Copenhagen Institute for Future Studies. That was my dream job, and while there I also launched their innovation department – while still being a student myself! One of the things we also did was create a learning game for the Danish Science Festival. We used role-playing games and narratives to drive a science curriculum. It was groundbreaking. We then got funding to create a new game where students were CSI investigators. It was amazingly good and 15 years later it’s still used in many Danish schools.

I left the Institute and set up my own innovation company, the first of its kind in Denmark, which was then acquired by Saatchi & Saatchi. I also set up a huge European project to develop methodologies for how to do innovation, especially strategic innovation. We got €10m of funding and it was the largest project of its kind. So I didn’t do much in games for a long time. Instead, I was focused on how to work in a structured way with radical early-stage innovation.

So where does Fog of Love come in?

I wanted to focus on stuff that was more fun because I worked all the time; I wanted to do something that was closer to my heart. So I began to play games again. I was amazed at how much had changed within board games. I was blown away! The last games I had played were in the Nineties! I think Carcassonne was the only modern game I had played. I had earned quite well so I could buy any game I wanted, so I just threw myself into this ocean of new games.

I wanted to play with my wife and introduce her to these games, but they weren’t interesting to her. I thought maybe I could make a game for her and at the same time, Fastaval began to focus more on board games. They set up a competition where you could create a prototype and you could win a prize. I wanted to participate in the competition, but I had never created a board game.

I tried to figure out what kind of game should I make for my wife. I wanted to follow my methodology for innovation, but just focus on her – a target group of one! I interviewed her and studied her response to different games. I tried to understand her cognition around games – what induces the experiences she has and what sort of things does she like or not like.

I’ve studied cognitive processes – how people think, how people process information, how they value things, how they are motivated – and that’s what I took into the development of the game. I learned that my wife was into narrative and theme rather than brain-burning games like Chess or Hive.

The most prevalent themes out there for games are taken from the geek universe – fantasy, science fiction and horror. It’s boring! It doesn’t mean anything! My wife likes romantic comedies. So I thought maybe I could create a game about romance and trying to woo a partner. She thought that could be interesting, but the game needed structured conflict. It wasn’t about solving a puzzle or fighting something or optimising an economy. It’s quite a different structure so I had to figure out what that conflict could be.

I had some ideas taken from my own romantic relationships as well, but I’m always trying to do some grounded research in the field, so I read a lot about love and relationships and whenever there was something I could translate into a game mechanism or something that could impact the narrative of the game, I made notes. I didn’t have a game yet, I didn’t have a goal, I just tried to figure out what kind of interactions were satisfying and interesting.

There’s quite a good community of board game designers here in Denmark, including Asger Granerud (Flamme Rouge, 13 Days), Daniel Pederen (13 Days), Kasper Lapp (Magic Maze) and Ole Steiness (Champions of Midgard). I spoke to all of these guys, and many other designers that had not been published yet, about my idea and – initially – most thought it was crap! But I was working in a very different way to what they are doing. They are creativity-driven in that they have an idea and then try to create the idea. I didn’t have an idea – I just had a space I wanted to explore and then build a game from this.

I was more focused on the experience first, rather than a fixed set of rules. This was so new and different to anything out there that I couldn’t just emulate and take other solutions and expect to have a game. It’s the same when I’m working in innovation; I build solutions from the bottom up. It’s a good methodology if you want to do something really novel and innovative.

How did the rest of the development go? Did you go back to those guys for more feedback once the game started to take shape?

Well even though they thought my idea was stupid, they still helped me. We have a great network of designers here in Denmark, and it would have been much tougher to develop the game somewhere else in the world. You get great feedback and I think some of the best games in the world will come from here over the next few years.

I did also get feedback telling me that there was no market for this kind of game. But I could see that there was a market for games that people could play with their spouse. There’s often a problem, quite similar to the problem I had with my wife, that it was difficult to convince women to play with their geeky men.

I worked on the experience and I had a lot of types of points you could get and ways you could increase the strength of the relationship, but there was a lot of stuff to keep track of, which was not all that interesting. What were interesting were the choices you had to make. I had cards where you make simultaneous choices, inspired by the crossroads cards in Dead of Winter, but taking the idea much further.

One of the things I realised was that I wanted the game to act as a conversation somehow. I play something, you respond, and there’s a back and forth. That’s key to a relationship and key to the romantic comedies I wanted to emulate. I found out that the simultaneous choices was good, so I included more of those cards and scrapped some of the other cards.

One of the problems I had was how to entice people to choose different each time they played. There had to be a tension that you didn’t know what the other person would choose, even if you’d both played the game before. That was the key means of learning who your partner is and making this relationship work. I had studied personality science and motivation, and a lot of this is used in predicting regular human behaviour and choices. This was useful as I could use these insights from personality science and put them into the game. Your character has a rich personality and your partner has a personality and you don’t know each other or what they would choose. That became the main mechanic of the game.

One review of the game led with the headline: ‘Playing Fog of Love made me and my husband break up’. While the game could’ve leant solely on a successful relationship being the end goal, why was it important for not every relationship in the game to work out?

My wife said that if you end up playing the game and your other half becomes an asshole, she wanted to be able to break up. Otherwise, it’s not a good story for her if she’s used in the story. It was important for her to have a sense of control, but of course, this made the game much more complex.

I had to work out how I could have this structure where you are together but you could also break up; where you could both win if you stay together or both win if you break up. It was difficult and I struggled with that for a very long time.

For Fastaval in March 2015, I developed another mechanism for the game called a break up cost; so whenever you make a public statement in the game, you increase the amount of break up cost, therefore you have an incentive to stay together. At the same time, if something happens, you could also break up. I toyed with this mechanism and it worked well, but some players could make the relationship good, break up and then win. It felt strange.

My game didn’t win the Fastaval competition. I was disappointed, but I had some free time and I knew I had something, so I signed up for a booth at Essen and I worked and worked on the game. I threw the break up cost mechanism away, and instead adopted some things from hidden role games. But that meant I had eliminated deeper choice from the game – it became all about bluffing. It changed the game completely and testers didn’t respond well to this. This was one and a half months before Essen and my game was worse off than it had been before!

Then I had an idea that you could choose your role, and I had my first prototype with this made three weeks before Essen. It worked amazingly well. It solved all my problems. It was a new way of driving a semi-co-op game. You have multiple winning conditions and you choose where to go, but you need to read where your partner is going because these winning conditions are not just for you; they are interactive. Normally a game with a set goal requires victory points or you have to kill something or solve a mystery, but if you are able to choose your own goal and these goals interact with other players, you add a social dynamic.

This social dynamic can make co-op games much more interesting. A regular co-op game is actually not about co-operation, it’s about co-ordination and how well the team co-ordinates. Co-operation is about trust and the possibility that you are not actually aligned. You can create some extremely interesting types of games with this social element, as well as more interesting stories.

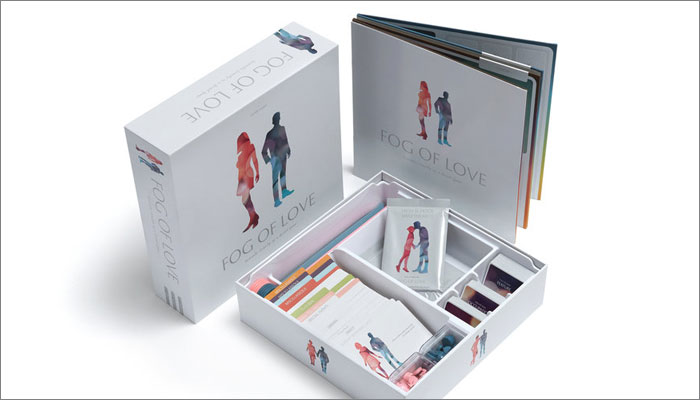

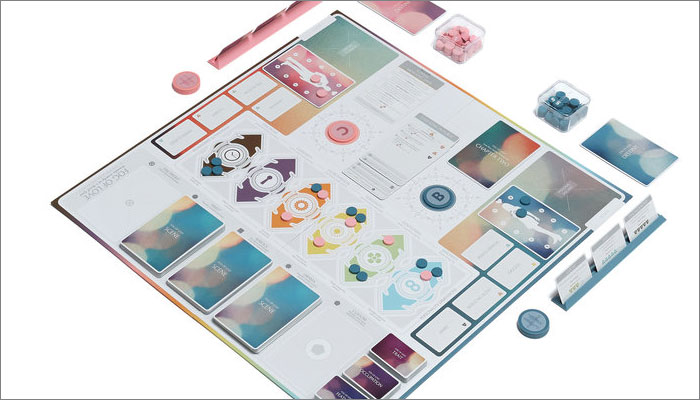

Aesthetically, Fog of Love has a very clean style to it. Was it important for the game not to have an overly fussy board?

My wife had full veto on everything and she didn’t like the look of a lot of games. They either looked boring or too geeky. I was showing the game at Essen in 2016 and I got a contract with Walmart. They wanted the game and fell in love with it.

It was curious because at the time, Fog of Love was unknown and the publishers I spoke with were reluctant. I had many problems with publishers. I knew the game could be big, so I wanted to work with big publishers. They didn’t take up the game and were afraid there wasn’t a market for it; it was too risky for them. Walmart know their customers and they have a huge percentage of women in shop in Walmart. It had been difficult for them to target this group but they saw my game and thought it was perfect for them. To Walmart, it was obvious this could fill a gap in their market. To publishers, they saw the same gap but to them, that gap meant there was nothing to sell.

The agreement with Walmart meant I had a large pre-order upfront, which in turn meant I could reinvest more into the game. So I hired a really good graphic designer to help with this. He had never done a board game before and so he wanted to make it beautiful but didn’t care much about usability. So we had a lot of back and forth, but he did a fantastic job.

My wife was always part of the decision-making process and she has a keen eye that I don’t have. Initially he made something that looked Victorian and quite occult in some ways. The pastel characters were still there but the visuals looked like they could have been on a tarot card. My wife thought it was emotional but not modern in anyway, so she pushed us in the right direction and the designer had a lot of great ideas of his own.

What’s next in the pipeline for you?

I want to make a trilogy. Fog of Love is about meeting and falling in love. Then I want to do a game about a mid-life crisis where you’re not trying to deduce who the other person is, you’re trying to figure out who you are! I have some interesting ideas for that and I think I can create something at least as interesting as Fog of Love. I’m slowly starting to work on that. It’ll be fun, deep and interesting.

The final part of the trilogy will be about the final years of your life before you die, where you look back on your life, your regrets and what you’re happy about. It’s more like a deep drama – who dies first or do we die together? Fog of Love is the comedy; the mid-life crisis is a drama, and then the last one is a tragedy.

I want to evoke different types of emotions. I want people to cry at the last game. Fog of Love is fun, but deep. The best romantic comedies are not just the ones that are fun, but are the ones that touch on some deep stuff. And now I have my own publishing company, Hush Hush Projects, I’ll publish these games myself.