Jenga creator Leslie Scott on how her approach to game design changed post-Jenga

Based on a game that Leslie Scott devised in the early 1970s with her baby brother’s toy building blocks, Jenga’s journey to becoming the household name it is today actually had a rocky start.

Aside from Harrods and a couple of small independents, no retail toy buyer was in the least bit interested in talking to a one-person, one-product company. The struggle continued for a few years until Hasbro licensed Jenga in the 1980s. Since then, Jenga has been an enduring success and its influence can still be felt in today’s market with the likes of Sensible Object’s Beasts of Balance and Hasbro’s official tie-ins Jenga Gold.

Post-Jenga, Scott remained in the world of game design with her company Oxford Games, but she intentionally changed the sort of games she set about creating. We caught up Scott to talk about this shift in direction, her top tips for fueling creativity and how she found the process of judging a new crop of game designers at this year’s D&AD New Blood Awards.

How did you first break into game design?

Well I didn’t so much break in, as leap without looking! Somewhat rashly, without any market research or without knowing anything about the toy industry, I decided to develop and take to market a novel version of a game that had evolved within my family.

Knowing a little more about the ways of the toy business may have helped me get Jenga off the ground, but then again, it may have put me off even attempting to launch it in the first place.

What do you think the secret of Jenga’s longevity is?

I wish I knew for certain. But my guess would be that it could be down to the fact that while Jenga appears to be a simple, even simplistic game, it is in fact remarkably challenging and quite gripping to play.

Has your design process changed much from when you developed Jenga to designing titles at Oxford Games?

Yes, and, no.

Post Jenga, I quite deliberately turned to designing games that I felt would appeal more to the gift, book and/or museum market. Together with a good friend, the graphic designer Sara Finch, the plan was to create a portfolio of games that could stand alone as good games yet were identifiably part of The Oxford Games Collection. So while a lot of careful thought went into designing games that would fit well within this collection, I relied (and still do) upon gut instinct when it comes to devising the actual play mechanics of a game.

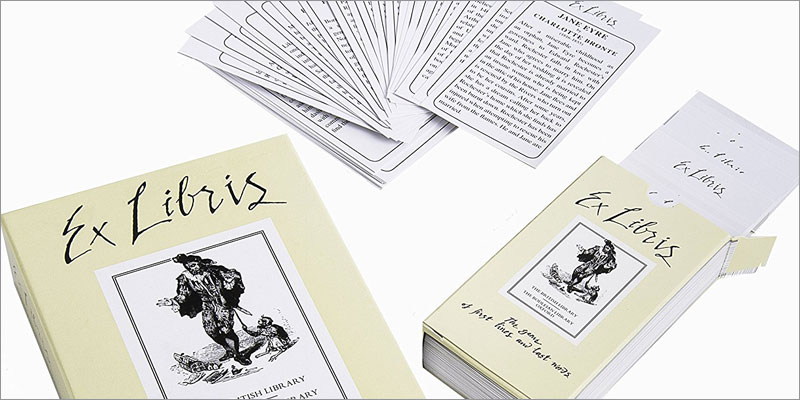

I confess that I do very little playtesting or market research before publishing a game. Of course, this is a daft way of developing any product, let alone a game, and I admit that there have been avoidable problems and several failures over the years. Yet, the most successful and enduring of OGL games – Ex Libris, Anagram, Flummoxed – were all published with very few tweaks to the rules and almost no testing. I believed that if I enjoyed a game, then there would be enough other people who would enjoy it, too.

I hasten to add that my daughter, Freddie (who is a professional product designer and runs OGL today) doesn’t approve of this somewhat cavalier approach. We are working together on a new game at the moment, which I assure you is being thoroughly playtested and re-tested before it sees the light of day.

You recently judged the games segment of D&AD’s New Blood Awards. Having seen a crop of concepts from new designers, how do you assess the current state of creativity in the world of game design?

I was very impressed with the whole process. Given that the designers were asked to work to such a tight brief (by Hasbro), it was remarkable just how many came up with concepts that were either totally original or at the very least, novel or interesting twists on older ideas. There were several games that I think could and should be taken to market. Clearly, there is a great deal of exciting talent out there!

Finally, what’s your top tip for fueling creativity?

Be curious – about everything. A novel idea can often arise from the unlikely juxtaposition of bits of information taken from very different sources.