KID Group co-founder Dan Klitsner on Bop It’s origins, his dream job… And the importance of champions

In the first of a two-part chat, inventor Dan Klitsner talks about the career he’s yet to have, rejection – and why champions are as important as sizzles.

Dan, thanks for doing this. Since Bop It’s celebrating 25 years, this seems like a great way to see out 2020. So first, I’m always interested to know: did you play with toys and games as a youngster?

Oh yes, for sure. I grew up playing typical board and simple card games, like cribbage, with my parents and siblings, as well as classics like Operation and Mousetrap. In fact, those were probably the most-golden family memories I can remember from childhood. I also loved toys; tin toys in particular. I collected them as a hobby. And Hot Wheels comes to mind as well; that was one of my favourites.

An emphatic yes!

I honestly think part of what drives me is I’m always searching for how to create more of those moments with my own family and friends. We do like playing games, of course, but I sometimes think I should also give a special mention to something most inventors subject their families to… Playtesting all their inventions, and appearing in multiple videos throughout the years.

Eventually, they start running in the other direction when they see their dad approaching with a prototype. I often joke that there’s probably a self-help group for children of toy inventors. They meet weekly to discuss how much they were used as cheap labour throughout childhood and never received acting credits.

I like it. Maybe call it Fair Play?! So you grew up playing games – how, then, did that become a living? How did you come to be working in the industry?

I was an industrial designer out of ArtCenter College of Design, and after a couple of years of design jobs – non-toy related – as well as working as an architectural illustrator, I saw an ad in the newspaper…

Sorry; when is this, roughly?

This would be around 1984. It said, “industrial designer freelancer wanted for new toy company – please send resume.” Since I’d always loved toys and games, I decided to apply. The company was Discovery Toys, based in Martinez, California and they sold toys the way Avon and Tupperware sold their products.

You mean like what? At parties?

Exactly; at in-home parties hosted by moms! Up to that point, they’d only sourced products, but were now looking for their own proprietary infant and preschool designs. We hit it off and, for the next five years, they were my steadiest freelance client.

And what did you take away from that?

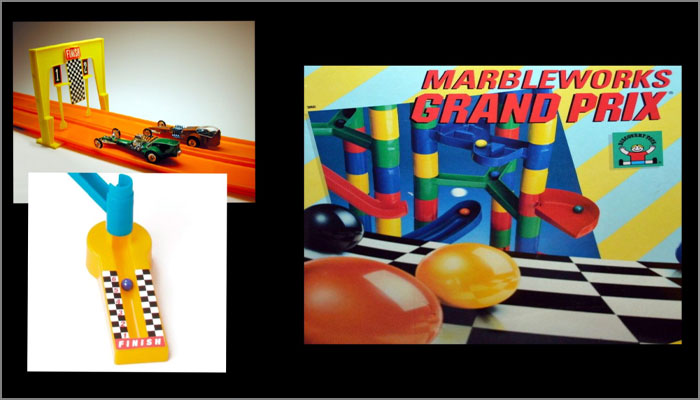

I learned a lot about the business from working with their internal marketing group and engineering. I designed several products that are still on the market. Most notably, Marble Works Grand Prix. They wanted their own proprietary, constructible marble track – and I wanted to make it more of a race instead of just an activity.

So this is a build-it-yourself marble run. What was its point of difference?

As far as I can tell, it was the first time a marble track was designed to have a winner, and kids could each race their own marbles at the same time. There were lots of ways for the marbles to pass each other, and the finish line showed who won.

Got it. And where did that idea come from?

It was probably inspired from something I mentioned earlier, actually. One of my favourite toys – Hot Wheels. On some tracks, there was a finishing flag at the end to determine the winner when you raced two cars. Over the course of designing several other toys with people at Discovery Toys, I heard tales of toy companies licensing ideas and paying royalties. I started to look into it, first in the preschool category and three-dimensional games.

It sounds then, Dan, like you didn’t feel it was your calling to invent toys. So, let me ask you: if you weren’t doing this, what would you be doing?

I’d be laying down bass-lines in a groovy funk band!

Really?!

Yes – I came from a musical family. Both parents were Broadway actors, and I grew up playing music. To do it for a living, though, I would seriously have to be 100 times better at playing bass! But sticking with my actual skill sets, I’d be a ‘travel illustrator’, something I still dabble in. Right now, I’m only doing that as a hobby on family trips and at conferences – or was, before the sharp decrease in world travel…

But when you travel, you’re saying what? You sketch locations?

Locations, yes; people, vehicles… The occasional piece of luggage. I have a site actually – www.illustratedtravels.com – where you can see my travel sketchbook journals from the last five or six years. And you can learn extremely interesting facts about our family vacations, like how we rated the fish ’n’ chips at each pub, or who won the card game that night. I really enjoy documenting trips with sketches and stories, and I think that’d be a fine job some day; to be hired as a travel illustrator, by a company that does exotic trips.

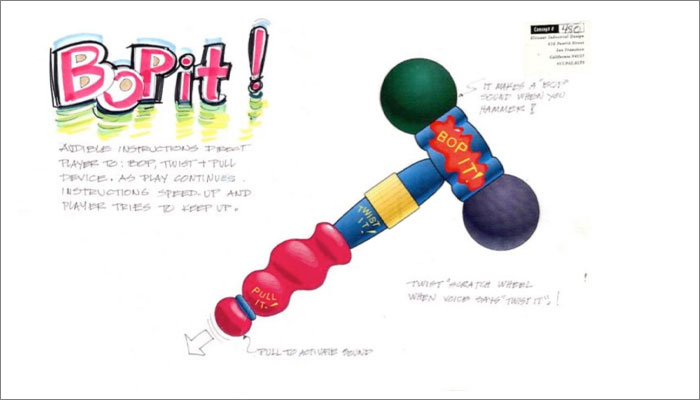

Well, let’s put a sketch in here; like an audition piece… Now, I almost daren’t ask, but – in your own words – you’re the inventor of the “world’s most annoying game” – Bop It. The story you tell about getting it to market is fascinating… Can you give us the background?

After 25 years, I’m more and more grateful and appreciative of the story of how Bop It came to be – and the perfect storm that had to happen. It was a combination of skill, insight, luck, relationships, timing, and a slew of individuals helping it become more than my initial concept in all the right ways.

It’s also proof that one of the only sure things in this inventor community is that it just takes one champion to believe in your idea, even if you’ve been rejected several times. The champion for me was a man named Bill Dohrmann; Head of Inventor Relations at Parker Brothers in 1995. The story actually goes back a bit further than I’ve told before… I was a freelance industrial designer and designing products for the electronics company Memorex. One of my projects was to design universal remote controls…

Universal? Do you mean remotes that worked on more than just a TV?

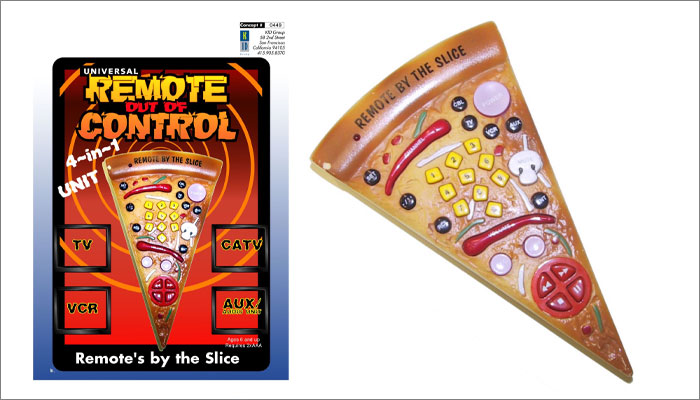

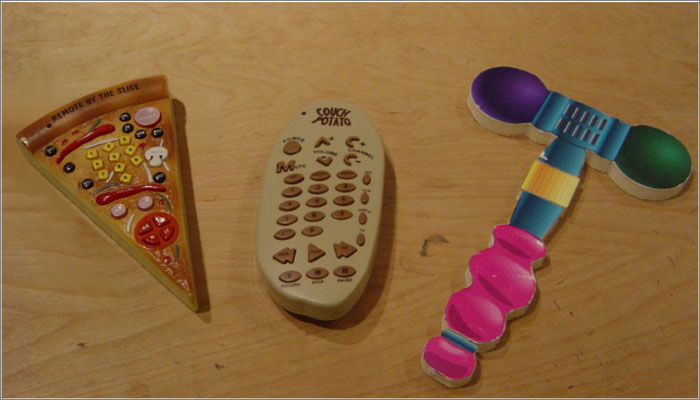

No; I mean remote controls that could work on any TV. And at the same time, I was starting to look into pitching inventions to toy companies… So it occurred to me to do a line of toy-like universal remotes for kids. I figured they’d have some playful themes and features on them. There was a Couch Potato remote, a Channel Surfer – like a surf board; a Remote Rock, like a pet rock spinoff; there was a skeleton in a coffin where his bones were the buttons… And Remote by the Slice: a slice of pizza, where the toppings were the buttons.

So really, this a lot of very different ideas?

Yes; it was a wide range. And actually, something I’d forgotten until I looked back through my archives recently is that I themed some of the remotes based on popular kids TV shows. The skeleton was pitched as having a Goosebumps license. I also thought Nickelodeon might be a good license because the network had lots of whacky kids shows at the time and is part of what inspired me to come up with something different that fit that particular brand. One of the ideas was a flat remote like the others but with crazy knobs instead of buttons. The other was more physical…

Okay…

As many have heard, initially the idea for one of these was a TV remote called the Channel Bopper. I thought of it as a way to make a TV remote fun – more “Nickelodeon” – by making it much more physical and with silly noises… It started out with lips for the volume up and down buttons, but later evolved into a twist knob to make it more physical. You bopped one side of this hammer on the table for channel up, one side for channel down; you pulled on the end of it to turn the TV on or off. And the volume was a knob in the centre that you turned like an old-fashioned volume control.

And if I’m understanding you, this is different from the other designs in as much as they’re still what I call function before fun?

Function before fun… Yes, I like that! In contrast to just pushing buttons on the remote, the bopper was the only one that was physical. It was intentionally just the basic actions you needed – if you needed to go from channel 1 to channel 43, you’d have to smack the hammer on the table 42 times… Something I assumed a kid would love to do. And again, very much like something you would see on a Nickelodeon cartoon.

So given the hammer idea is the other way round – fun before function – how did it come about?

Why did I have the idea of making a physical hammer? I credit it to an insight early on that I picked up from a toy-industry veteran named Chris Conger. He pointed out how watching the actions and movements of the kid was the way you could tell if a toy was successful – not just looking at the toy. I translated this into the idea of making the user use large motions with their arms and hands instead of pushing the little buttons that you use with your thumbs. You can see where this is going, but of course I didn’t at the time…

Well, it’s only obvious because you’ve already joined the dots! Just so I know, though, did you pitch all these remotes?

I did! In fact, I licensed the line to MGA. They were called Remotes Out of Control. In that meeting, though, I remember the founder of MGA, Isaac Larian, thought the Channel Bopper was too physical compared to the others – so it wasn’t included.

As a remote, it was rejected…

I tried pitching it again a few months later to Tom Dusenberry, then an executive at Parker Brothers, and I remember him passing on it and saying they wouldn’t do a “game-like” TV remote. But with a shrug, he suggested, “Maybe it’s not a remote…”

“Maybe it’s not a remote…” And buried in those words is the end of a definite no!

Yes, but I didn’t yet envision how that would work! Things always seem obvious in hindsight, don’t they? But I still saw the idea as something that YOU did: actions to change channels… Not that IT would tell you what to DO, like the light-up memory game Simon. So the mock up sat near the back of my desk for six months in the large pile of things I didn’t know where to file.

Okay. That I didn’t realise: you more or less put it aside for a time?

For quite a time! A few months after the last pitch, I got a call from Liane Czirjak who was Inventor Relations at Tiger Toys. I’d already licensed some electronic-game ideas to them. Anyway, Liane said that sales of the LCD games they’d been so successful with were now falling off – and did I have any new, innovative ideas? Well – literally while I was listening to her on the phone, I saw the mock up for the Channel Bopper still sitting there on my desk.

Because you’d still got it on your mind?

More because I’m terrible at putting things away! But then I thought about the “maybe it’s not a remote” comment.

You know, one of the reasons I wanted to interview you, Dan, is because this journey is the antithesis of how some people think an invention comes about. It’s not one idea. It’s not a flash of inspiration. It’s not everyone seeing it and thinking you’re obviously a genius and egging you on! It’s a slow, foggy development, interrupted by rejection as you join lots of dots…

For sure. And I keep saying, it’s only obvious with hindsight! So even when Liane called, I was still a long way from Bop It. In fact, I’d started thinking maybe I could put a screen on the Channel Bopper and turn it into a very physical LCD game.

And what was that idea; what was the game?

The gameplay was a bit like Whack-a-Mole: you were trying to bop the hammer end on the table, timing it to smash characters that popped up. It had potential, but I knew it was difficult to see what was on the screen while you were bopping it. That’s also the way Tiger Toys saw it when it was submitted – and probably why they rejected it. So I took the concept back to try and figure out how to improve it… I thought maybe I could remove the screen and make it into a more physical version of Simon, with lights to memorise and actions to perform.

But it came to nothing?

Well, it turned out to be much harder to do compared to Simon because adding physical actions made it much more difficult to remember the moves – and putting in four lights made it more expensive. At the time, however, there were new and cheaper chips with greater voice capability, and several toys were starting to show up with more sounds – talking fire trucks, stuff like that. I was already using the speaker for the sound effects so I tried a version with a voice telling you, “Bop red, twist yellow, bop green, pull blue…” corresponding to the colours on the action items.

So that had a recognisably Bop It element. But you weren’t happy with it?

No. I mean… As a memory game it looks like it’s okay. It turns out, though, that it’s even harder to do a memory game with vocal commands. It was an intriguing, new, challenging memory game – but just not very fun. Your mind doesn’t memorise the “audio” pattern in the same way as Simon when you see lights giving you the pattern that continually test the length of your memory. I thought maybe it doesn’t get longer and longer… Maybe it just does four moves at a time? It was better, but I didn’t like the way the player stopped every four moves and waited – motionless – for the next four commands.

You use the word “maybe” a lot. It’s dangerously close to the technique of saying “What if…”

That’s exactly what happened next! In what I credit – with eternal gratitude – as my biggest, totally counterintuitive epiphany, I was thinking “What happens if it’s just one move at a time so you have to keep moving? Would you ever fail? And, to test that, I did a recording of my voice on my computer, saying the commands. It felt better, and I liked how it got you into a rhythm instead of waiting between sets of moves.

Was there a trade off, or a downside?

It did seem too easy. And I thought, “Oh, well… It probably won’t be challenging enough.” Again, this seems obvious in retrospect – but before going back to the drawing board, I tried gradually speeding it up every seven or eight moves. Even though it was just one move at a time, I could feel my hands get a bit confused. I could tell – even with the rough foamcore mock up – that it was confusing to switch from twisting to bopping to pulling, and that, eventually, you’d make a mistake!

It’s such a long way from where the idea started; I find it fascinating. It’s a lesson to anyone that insists their current idea is THE idea…

And when you think about it, really, it’s the exact opposite game compared to where I started; a physical memory game using light patterns! People make the comparison of Bop It to Simon, which is a great insight into the DNA… Mainly I think that’s because people relate to the sounds, and following commands dictated by a device. But when they say, “Bop It is like Simon” I like – nerdily – to point out that, in regard to the actual mechanics, they are, in fact, opposites.

So let’s explore that. Could somebody, in theory, have picked up Simon and said, “Let’s do the opposite of this…” and have invented Bop It?

Hmmm. In hindsight, theoretically, yes… But it’s more of a way to explain how they use almost opposite senses and forms… Simon is a stationary, flat, table-top game that tests your ability to memorise ever-increasing sequences of light patterns using your fingers – almost a zen experience… In contrast, Bop It is always moving, it’s in your hands, and there is absolutely NO memorisation. It’s physical, and you just have to do what you’re told. I think the two games use very different parts of your brain, and I sometimes wonder if the success of Bop It is partly due to how it somehow captured the difference in generations.

In what way?

Bop It is more like the electronic game for the generation that was raised to have a shorter attention span, I think. Also, probably the most-overlooked difference between the Simon and Bop It DNA is humour. It’s easy to think of lots of ideas based on the Bop It “command-response” gameplay, but unless they have that quirky, humorous part, they don’t seem to fit.

My favourite part of the Bop It story – I won’t go into it in depth because I think I’ve told it in many interviews already – is one thing that happened when I was first pitching it to Bill Dohrmann. He took the time to try the mock up, even though it was just simulated, while listening to the audio commands on the video. He really got it. He thoughtfully looked up and said, “We aren’t doing these kind of games right now – but we should be.”

Brilliant. I hear that part of the story and it feels to me that Bop It was like an alchemist’s spell… It’s transformative; to the point they’d bend the company to fit the toy – or game.

It was that moment when you realised that you connected with the right person at the right time at least to get your vision; something that – after many years – I believe very few toy inventors take for granted anymore.

It feels like we’ve only just got going here Dan, but we need to wrap it up! So I think, if you’re happy, we should pick it up again and do more than one piece with you. For now, let me ask one more thing… When you pitched Bop It you made a short demo video with a foamcore cut out! Would it have been better to have had a fully-working prototype?

I think that video has done more to both help and hurt new inventors than anything I’ve ever done. How it helps is to say that – if you’re pitching an idea – it’s a good screen test to see if it can be understood before investing in a prototype, and it makes a good impact in 15 to 30 seconds. However, this only applies to concepts you can mock up in such a way as to be convincing.

So it did work and CAN work… But it’s not bulletproof?

Yes. This is very important… It can work as long as there’s no technology in the idea that’s unproven. If you show a concept that uses antigravity for instance, it doesn’t matter how good the video is, it’s probably not going to sell until you prove it. If it’s a concept that’s easily conveyed and convincing in a video, the benefit is the video pitch may be the one thing you have control of as it goes through a company’s weeding-out process. Prototypes break, or they don’t quite deliver the magic that you envision in the final product, so I believe certain concepts work better as a “fake video”.

Right. That makes absolute sense. So what’s the downside?

The other half of the story of that Bop It video is something that people over the years maybe don’t realise… Although the model wasn’t technically a working prototype, in a way it was. I sent in a foamcore model that indeed could be played with – to the soundtrack of the video. I also showed the legendary Bill Dohrmann how to pretend to follow the commands of bopping, twisting and pulling while listening to the video… And made sure he knew that, when he pitched it internally, he should NOT just show them the video.

Ah! Is that right? Okay… So Bill Dohrmann is there. He’s familiar with the idea, he knows the video and he has a foamcore model in hand? So he’s equipped – well, equipped and trained, really – to champion Bop It for you internally?

Exactly. Bill was to hand others the mock up, turn on the video and let people bop, twist, and pull it as the sound sped up because it was harder – and a lot more fun – than it looks. When playing with the foamcore mock up, you could feel instantly that it confused you to have to do those three different actions… Most importantly, it made you laugh a little, as well as the other people watching you. So that was a huge reason why Bop It made it through the process – it’s much more than the video; in a way it was a working prototype that people could experience.

Brilliant. That’s really insightful; I think it helps to understand the context of a video or sizzle, and the place of a prototype. And out of curiosity, then, do you NOW make fully-working prototypes?

Well, as you may know, there have been many Bop It variations since then, and the subsequent prototypes we’ve developed have probably been as thorough and complex as the foamcore hammer was simple. Thanks to my incredible KID Group partners – Gary Levenberg and Brian Clemens – we’ve not only built almost every subsequent prototype, but we also do the final music production, and final coding… We spend a lot of time providing industrial-design inspiration, and brainstorming on what the next Bop It should be. I should also say: we’ve worked with many other talented designers over the years

But even you don’t have a Hasbro hotline that gets you straight through to stage five or what have you?

Ha! No, not at all. In fact, for ten years we tried to get Hasbro to do character Bop It’s for instance. We had an amazing presentation showing computer animations of how you could take R2-D2 and Minions and Marvel characters and turn them into a Bop It. But it wasn’t until Hasbro had a request from Lucasfilm asking if they could do something with Bop It that the idea was “right”… Then we built a fully-working R2-D2. So I guess timing and execution played a big part in that, but – yes – in that case, we needed working prototypes to seal the deal.

Fantastic. Dan, I’m loving this! Let’s take a break, though… When we pick up, we’ll come back and chat more about creativity, Perplexus and the advice you’d give inventors!

—-

To stay in the loop with the latest news, interviews and features from the world of toy and game design, sign up to our weekly newsletter here