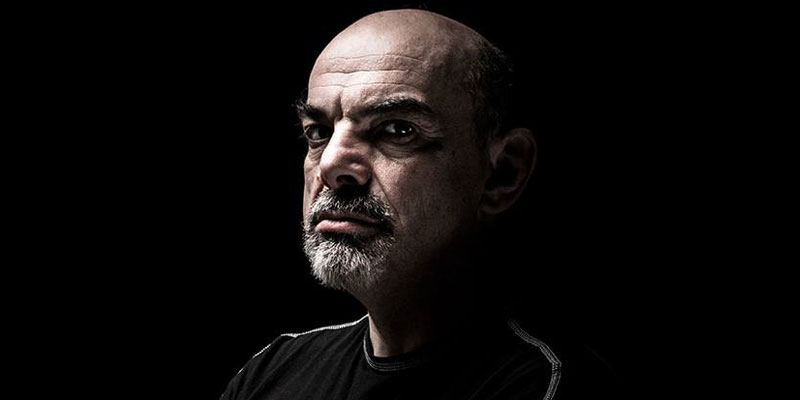

Kingdomino designer Bruno Cathala on the honour, joy and stress of his first Spiel de Jahres nomination

Bruno Cathala has been designing games for 15 years, with some of his popular creations including deduction title Mr Jack, Days of Wonder’s Five Tribes and the widely praised 7 Wonders: Duel.

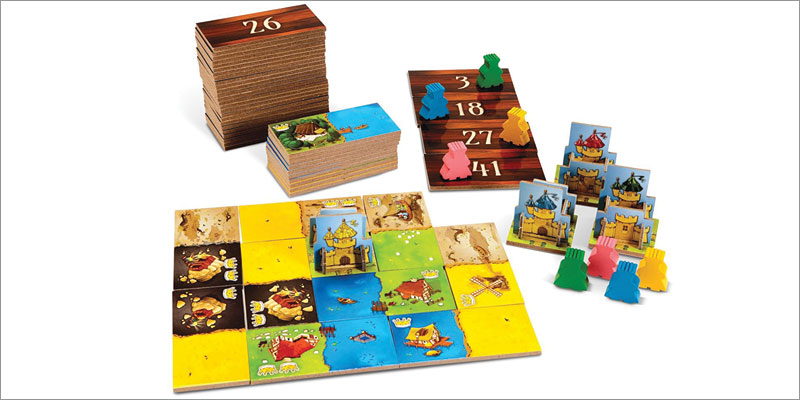

While almost all of his titles have enjoyed some form of awards recognition in the way of recommendations, nominations or actual wins, it’s his most recent game, the tile-laying title Kingdomino, that has thrust Cathala into the spotlight due to its Spiel de Jahres nomination.

Spiel de Jahres (translated into English as Game of the Year) is the industry’s most prestigious award for board and card games and is given annually by a jury of Germany game critics. Since the launch of the awards in 1978, previous winners have included Rummikub, Settlers of Catan and Codenames and while a nomination is said to triple sales of a game, actually scooping the Spiel de Jahres title can lift a game to sales of around 300,000 to half a million copies (according to Stewart Woods’ book, Eurogames: The Design, Culture and Play of Modern European Board Games.)

Cathala has been involved in the overall awards before, when his and Antoine Bauza’s 7 Wonders: Duel was nominated for last year’s Kennerspiel des Jahres (a spin-off award recognising excellence for more complex games) but Kingdomino marks the first time that Cathala is up for the award he deems the game world’s equivalent of an Oscar.

We caught up with Cathala to talk about the development process behind Kingdomino, as well as how he approaches collaborative game design, what he makes of the current state of creativity in the games space and his joy over a Spiel de Jahres nomination.

How did you break into the world of game design?

As far back as I can remember, I’ve always be passionate about games; any kind of game. But I discovered ‘modern games’ when I was 20, reading a French magazine called Jeux & Strategy. This helped me discover there was a life after Monopoly.

I discovered that there were people creating games (it’s strange but I never thought about who was creating games before). This gave me the idea that one day, it would be great to create my own game. But at this time, it was too early. I didn’t feed myself with many existing games to be able to create something good enough for the market. So for years and years, I was only a gamer; buying games, reading rules, teaching these rules to friends.

During this period, I was working as R&D engineer in material sciences, I was involved in sports with my rugby team, and I also became a father. As you can imagine, I didn’t have so much free time to create games. But that all changed in 1999. I broke my knee so there was no more rugby and I divorced, so it was time to work on my first game design project. It was the best way to focus my mind on something positive.

I created Sans Foi Ni Loi (the English title is Lawless) in the following weeks and it took me three years to get it published.

Has your development process changed much from your first game to your most recent creation?

Maybe it will seem strange, but no, it hasn’t changed at all, probably because my development process is exactly the one I learned as a R&D engineer. Even though I had not experimented in developing board games when I started out, I had experience in the development process with my former job.

You first have an idea and then you have to build experiments to demonstrate if it’s good or not. During this process, you have to study the results of a lot of different input parameters in order to find the best final tuning. And at the end you have to write the process (in the world of games, we call that ‘rules’).

I worked that way for my first game design. And it’s still the same way today.

On several games, you are credited as a co-designer. How does this process of collaboration on a game usually work?

Well, it’s not that easy to answer this question because even if I’m always the same guy, I don’t work the same way with my different partners. They all live far from me, which means that we work a lot by mail, phone and Skype.

For example:

• Working with Bruno Faidutti is, for me, like a race. That means that if I really want to give one of my ideas a chance, I have to work faster than him (and he works very fast).

• Working with Serge Laget, we first need to meet together. We need to have a good lunch, with good wine, sharing a lot of things not connected to games, speaking about life, politics, or any kind of topic with passion. And then we start to brainstorm together.

• With Ludovic Maublanc, one of us gets leadership of the project for some time. He is in charge of development, makes his own experiments, and stays connected to the other one, making reports of the tests. And then, the leadership changes and role are reversed. And so on and so on, until all is finished.

• With Antoine Bauza, we have meetings, but not a lot of them. We won’t have prepared anything before the meeting. We drink a coffee, discuss, and it’s finished. We always agree very, very fast. It’s as if we didn’t need the meeting.

Can you give us an insight into the development process behind Kingdomino? Where did the concept come from?

The starting idea came from dominoes. I just wanted to play with dominoes, but I was trying to refresh the old way of playing with them, instead making something more modern.

I was fascinating by dominoes as an item and I wanted to make a game I would love to play myself. I also thought it could make sense for other people, because everybody had an experience with dominoes as a child, so for that I needed to try to keep the rules the simple as possible.

Kingdomino is up for the Spiel de Jahres award and you’ve been nominated for – and won – many awards in the past. Do you place much importance on these kinds of accolades?

Well, when I’m working on a new project I never thinking about what I have to do (or not to do) in order to try to get an award. In fact, my development process is quite selfish. I’m always working on the game that I want to play myself.

When it’s finished, the second part of my job is to trying to share my convictions with other people (publishers first, followed by gamers), so during the development process, awards are not on my mind.

But I’m always honoured when I learn that one of my games gets a nomination or an award. Even if I never try to get them, being honoured that way means a lot to me, and that goodwill and recognition goes directly to my heart.

With Kingdomino, you have awards and then you have the award. Spiel de Jahres for a game designer is the same as an Oscar for an actor. This year, after 15 years in game design, for the first time (and maybe the last because there are so many great games each year) I got a Spiel de Jahres nomination.

It’s amazing to me. I feel happy, honoured and stressed. And I’ve still got six weeks to wait. I don’t know if the jury will think I deserve the final award or not, but if Kingdomino does win it, it’s going to be difficult to avoid shedding some tears,

What games do you currently enjoy playing? And do you play your own games once they are published?

These last months, I’ve fell in love with three games:

• Captain Sonar, because it gives such incredible and different experience to players.

• Flamme Rouge, because it’s easy, clever and so elegant.

• Santorini, because for a fan of pure and beautiful abstract games like me, it’s a must have.

And yes, I’m still playing my own games after they have been published because I designed them for me as the first customer. This also explains why I like to design expansions for my games that I still play again and again.

What do make of the current state of creativity in the world of game design?

I think that creativity level is still very high in world of game design. Look at Captain Sonar for example, or the legacy system created by Rob Daviau.

But a game doesn’t need to be absolutely creative in his mechanisms to be a very good game. It needs to create something fresh and unique in your mind after playing it. If it does that, you don’t mind if the mechanisms are not fully innovative.

What advice would you give to anyone out there with an idea for a game but no idea what to do next?

First I would say that having a game idea doesn’t make you a game designer. Having an idea is quite is just the beginning. It’s the visible part of the iceberg. Transforming this element into a real game takes a lot of work.

To become a game designer, the first thing you have to learn is patience. You will need to built your prototype, to playtest it, modify it, playtest it, modify it – again, again and again. You have to do this with a lot of different people (not your family or friends who always think that what you do is incredible).

You will feel excited and disappointed, excited and disappointed, again and again.

And at the end of the process, you will have to really work a lot to write an understandable and clear rules booklet. Only then it will be time to try to contact a publisher.