Magic Mountain co-creator Jens-Peter Schliemann on the benefits of bringing ‘toy-thinking’ into game design

Jens-Peter, it’s great to connect. To kick things off, how did you find your way into game design?

When I was around 13 years old, I read an article about Alex Randolph – the designer of games like Twixt and Enchanted Forest – and I thought ‘I want to do that!’

When I was a student, I was very good at mathematics and I studied mathematics – but I wanted to make board games. In my student dormitory, I was surrounded by very creative people… The man that lived below me played classical guitar for six hours a day! That creative atmosphere gave me the courage to take the creative path.

I didn’t know if I would ever make money from making games, and it’s the same even when you sign a contract with a publisher. You never know how a game will do commercially, so I feel I do live like an artist, but it works! And it’s my passion!

Did you dive straight into designing or did you work in-house at any game companies?

I did a collaboration with Michail Antonov on abstract titles, and that helped me learn a lot. Another collaboration was with Team Annaberg, which was a group of four people. As part of this group, I did some project management for Winning Moves Germany. I also partnered with Kirsten Becker on some children’s games, while Team Annaberg focused more on games for adults. These partnerships helped get me started.

Also, in 1995, at the Göttingen game designer event, a scholarship was launched for new game designers. You win a grant of €3,000 and get to take part in beneficial practical experiences. I was the first winner of this grant and I’ve since spent years on the Jury for the award – one of the practical experiences for the winners now is one week with me! They can see my projects and how I try to realise them, and we can discuss how I work with publishers.

It sounds like a fantastic initiative.

Yes, I really like it – and I know how important it was for me. Also, new board game designers have a burning passion for what they’re doing; I like spending time with people like that.

This year saw you win the prestigious Kinderspiel des Jahres award for Magic Mountain, a co-design with Bernhard Weber. How exciting was it to scoop that accolade?

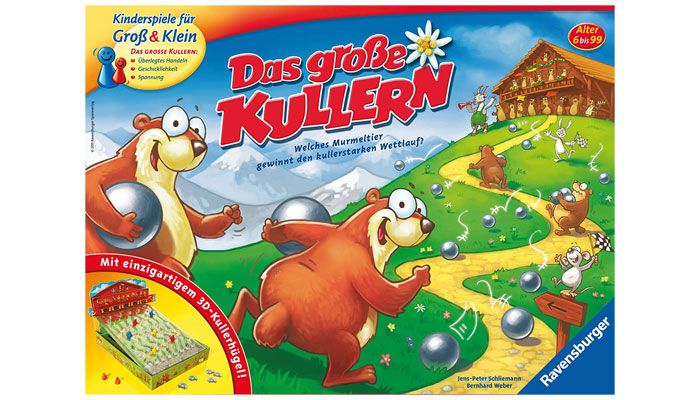

I’m glad we won the award, because of what it does for two arguments of mine… In 2010, myself and Bernhard also published a game that had a ball track. It was published by Ravensburger as a children’s game called Das große Kullern – or Roll & Go. We were not happy with the realisation, both in terms of the materials but also our rules. It was a bit too complicated for pre-school children, and our main idea was to make a ball track game for pre-school children. If you look at pre-schoolers and how are amazed as they follow a ball on a ball track, it’s wonderful. That was the start of the idea that became Das große Kullern.

Ah! So you felt you had unfinished business with the idea of a ball track game for pre-schoolers, and that’s where Magic Mountain came from?

Yes, we decided to build a new game that had some elements of the Ravensburger game, but Magic Mountain is very easy going and you’re immersed in the game with the first roll of a ball.

Did that make Magic Mountain a tougher sell? The fact it shared DNA with one of your previously published games?

It was a risky situation for us because when we took the new prototype to companies, we knew they could say “Oh, you published a similar game with Ravensburger and it didn’t sell well – we won’t touch it!” That said, this time with this game, we got the Kinderspiel des Jahres!

Sometimes, when you have an innovative idea that hasn’t been done before – like a ball track game for pre-schoolers – you have no roadmap around how to make it. If you do a tile-placing game, you know lots of games like it and what people want and expect from that type of game… For innovative games, you need to be like a scientist. You need to improvise and look in every direction at what’s possible. It’s a complex process of creative ups and downs, discovering how fun it is, how it flows… Like a scientist, you need time to find these things out.

Amazing – and you said the success of Magic Mountain helps two arguments of yours… What was the second?

Ah, yes! Well, I like easy-going rules, but in Germany, product managers at companies often want to add more complexity or extra elements. With Magic Mountain, I can now argue that simplicity is best!

Ha! Yes, two powerful arguments… ‘My innovative concepts will be proved great eventually’ and ‘Simple rules are the best’.

Yes, and I should stress, I test simple rules. I always playtest ideas with children and they prefer games to be easy-going like this.

What was it like working with AMIGO on the game?

They have been great. They always informed us on any big steps they made with game and were great communicators. It was a big effort from the team, because AMIGO usually do card games… We showed them the game in 2017 and it was published in 2021, so it was a long development process.

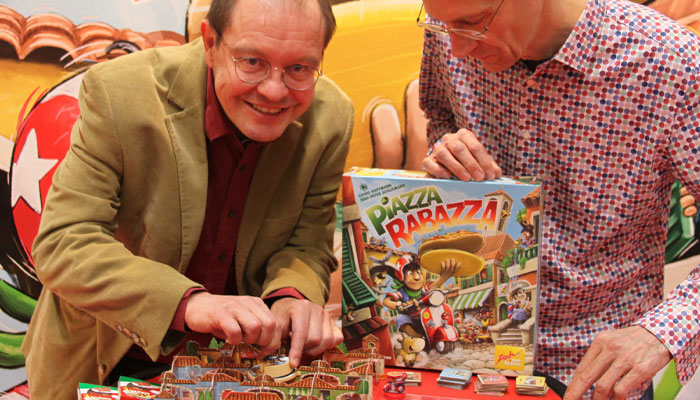

Magic Mountain also has real table presence. It really catches the eye. It’s the same with your other recent game, Piazza Rabazza, co-designed with Guido Hoffman. I saw it at Essen and the Zoch Verlag stand was always busy with people playing it – or watching people play it! Is that ‘toyetic’ element something you always look to create with your designs?

I like games that have a tactile quality. Compared to digital games, it’s a real strength that our medium has. If the ‘toyetic’ element has a clear function to the gameplay, then it can define the game – it can often convey how to play the game better than the rules.

I see what you mean. So like the shaking town in Piazza Rabazza or the sloped board in Magic Mountain, you see it and you get a real sense of the gameplay without even reading the rules.

Exactly. It’s a type of rule that you didn’t have to explain; the functionality of the piece does that for you. It’s a big benefit.

One of my strategies is to look at what’s coming out of the toy industry and built a game set-up around it. I love games like Loopin’ Louie that are very toy-like. Toy-thinking has the power to ignite the fantasies of children and game-thinking can design the process around how to play. The two mindsets go very well together.

We’ve mentioned Magic Mountain and Piazza Rabazza, but are there any other examples of games you’ve designed that have toy influences?

Yes, lots of my games do! One of my first successful games was Magician’s Night, which I co-designed with Kirsten Becker. It was published in 2005 and was also nominated for the Kinderspiel des Jahres.

Kirsten had the idea for a game that you played completely in the dark with some glow-in-the-dark elements. That was the creative task we set ourselves, and the final game won several awards and did well in Scandinavia – I think because it gets dark in the afternoon there!

What were some of the challenges involved in designing a game that you play in the dark?

Well, we quickly found that rolling a die or holding cards just didn’t work when you sit in the dark. A lot of the usual board game elements didn’t work for what we wanted to do. We had to look at other areas to find creative solutions… We saw coin pusher machines that you find at fun fairs and realised our board could be like that – where you’d push something onto the board that pushes something else off of it.

I’m glad we weren’t put off by the challenges, because it encouraged us to think outside of the box creatively and it’s something I still do today. It also led to one of our most successful games as it sold around 120,000 copies.

We’ve mentioned a few of your co-designers; Bernhard Weber, Guido Hoffman, Kirsten Becker… What appeals about working with other creatives?

Back one summer when I studied mathematics, I was wrestling with a mathematical problem… I didn’t eat, I wasn’t noticing the weather, I couldn’t stop thinking about it – it lasted all summer! When I realised how I had been acting, I was a bit afraid… It was in that moment that I realised I wanted to work with other people.

Embarking on a creative process alone is often associated with solitude. You lock yourself away and start an intense process that’s usually very different from your everyday life. I find it’s much nicer to work with someone else so you don’t have that feeling of solitude.

What do you think is the key to successful design collaborations?

Choosing who to create games with is a very important decision. My experience is that it’s helpful to collaborate with someone who is socially and politically of a similar mindset to you. If you are in the creative process together, there are times where you’re making important decisions almost every second. You can’t discuss every single decision with your partner, so sometimes you need a kind of unspoken bond; you need to be in a kind of flow together.

On the other hand, I have a collaboration with Guido Hoffman on Piazza Rabazza. Guido studied art and can do incredible illustrations for games, whereas I have more of a mathematical mind. If you can partner with people that have different talents from your own, that can be very helpful and make for a great partnership.

Jens-Peter, this has been great. I have one last question. How do you fuel your creativity? What helps you have ideas?

With Magic Mountain, the idea came from seeing the joy children experienced with marble tracks, so sometimes watching children and seeing what they love to do sparks ideas. Another aspect for me is looking at toys and how they can be implemented in a game.

I also like being guided by a creative task, like ‘Can we design a game that will be played in the dark?’ You’ll often uncover lots of connected ideas while trying to find a creative solution to your original task.

Great stuff. Thanks again Jens-Peter; let’s tie-in again soon.

–

To stay in the loop with the latest news, interviews and features from the world of toy and game design, sign up to our weekly newsletter here