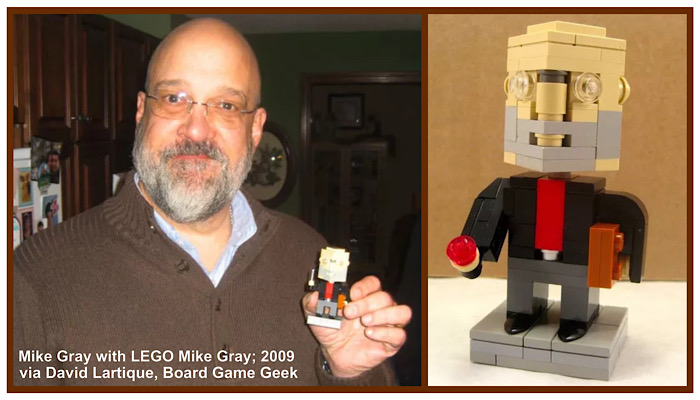

Milton Bradley and Hasbro inventor-relations guru Mike Gray looks back at his amazing career

Mike Gray! I.D.I.O.T. winner, game designer, inventor-relations guru… And once described by Tom Vasel as, “the wisest man in all of board gaming”… So! How did you first get into games?

I got into games as a child. I was the youngest kid in my classes and never very mature. Ha! When you sit down to play a board game, though, you’re all equal. Suddenly it’s as if you have everything you need… You bring your mind with you, but the game provides everything else. So playing games gave me an opportunity to be on a par to feel included, or worthy maybe… An opportunity for me to be with other people on a level basis.

Right. Games can be a great leveller.

So I played chess with some friends when I was like seven… In high school, I joined the chess club and worked my way up so that when I was a senior, I was captain of the chess team in Toledo, Ohio. It’s a big city and our team was rated second best. I also played Avalon Hill games with my few friends – usually guys who’s names began with a G… Because we sat in alphabetical order; they were the guys that sat next to me.

And at what point, Mike, did you say, “Well, I love playing games. Maybe there’s a way that this could be my job…”?

Well, I submitted a game idea to Avalon Hill when I was 11. It was pretty much just an idea based on a book report that I did. I got a nice rejection letter from a guy called Tom Shaw… And later, when I got into the game industry,

I ended up playing Bridge with him.

You didn’t go straight into the industry from school, then?

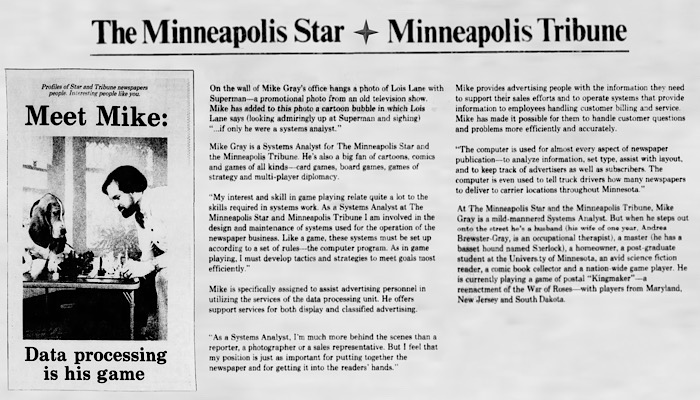

No. I had a job in advertising and then data processing at a newspaper, The Minneapolis Star and Tribune. I really hadn’t looked at toys and games as a career, but then a friend brought me a help-wanted ad for a game salesman. I applied for that – and didn’t get it. Then another job came up, this time for a game designer. I applied with a letter saying, “Gaming is in my blood…” I remember writing that line. And that got me an interview with Milton Bradley.

Wow. What year was this, Mike?

This is back in 1977. I went in and interviewed at the Milton Bradley office in Massachusetts. They didn’t really want a boardgame designer, though… They wanted a computer-game designer. This was back when computers had maybe 48K of memory. I did have an Apple 2 with a few games, but I wasn’t what they were looking for. In any case, my plane didn’t take off until later in the day so I had lunch with a bunch of guys from the boardgame group and – fortunately – they liked me. And I showed them some stuff, like a newspaper article about me that had a full page of me playing chess with my Bassett hound Sherlock. I said in the article that he’d never lost a game…

Ha! Well. Bassetts are a smart breed. And where did that article come from, Mike?

From time to time, the Tribune would run an article on its employees. I’d also met a writer for Minneapolis Magazine. She did an article on me called Play It Again, Mike instead of Play It Again, Sam. And the stuff I showed them also had a couple of game-review articles I’d written ahead of Christmas. Anyway, I flew home… A few months later, I got a call from personnel asking me to talk about the game-design department. They had two game designers. One of the guys was looking to retire so they needed another guy.

Now we’re talking!

They said they had a hiring freeze on, but that – in three months – they’d want me to come in and interview… And see what kind of games I could design. So could I do some work; Show some ideas, some artwork – maybe the rules? In that three-month period, I designed eight games.

EIGHT? Wow. Okay!

Well, they weren’t complicated; they were the old Milton Bradley type games, with cards and dice and a pathway; stuff like that. They had little spinning wheels with a button that made things spin and the path would change. And I did all the artwork for because I was in advertising and minored in art at college. Eventually, I went in with these games and those articles. When I interviewed, I just said: “You know, for me coming to work at Milton Bradley would be like Dorothy landing in Oz…” You know, like it’s all in color now…

One of the great moments in cinema! Lovely analogy; love it.

Well, they kinda liked me because I was really into games. And you know, back then, they were kind of into dropping marbles down a tube and having them maybe roll around and fall in a hole – just simple games. But they were getting into computer games at the time. Anyway, they said, “Our senior vice president would like to meet you.” His name was Vince Martin. So I go up all these stairs to this wood-paneled office; leather furniture with the brass tacks in it, you know?

I do!

So he’s sitting at this big, wooden desk; a much older guy. I was like mid twenties, I think; 28 maybe… I sat on one of the sofas. Then he came and sat next to me – started making conversation: are you married? What does your wife do? And I said, she’s an occupational therapist. And he said, “Oh, my daughter’s an occupational therapist – so it was like, ‘Ding!’

Jackpot!

And then we’re talking and he says do you have a picture of your family? And I said yes, but all I had in my pocket was a picture of me, my cat and Sherlock, the Bassett hound… And he goes, “Oh! I have a Bassett hound!”

Ding-ding!

Right?! So we hit it off. After I went back downstairs, another vice president came in, Mel Taft. And he said, “Well young fella, I hear you want to be a game designer… When can you start?” And I explained that my current boss wanted me to design the new advertising computer system for The Minneapolis Star and Tribune – a five year job. I was going to be in charge of designing it, so I said, “I’m going to need two months to train somebody to take my job. I can’t just leave…”

Was that risky?

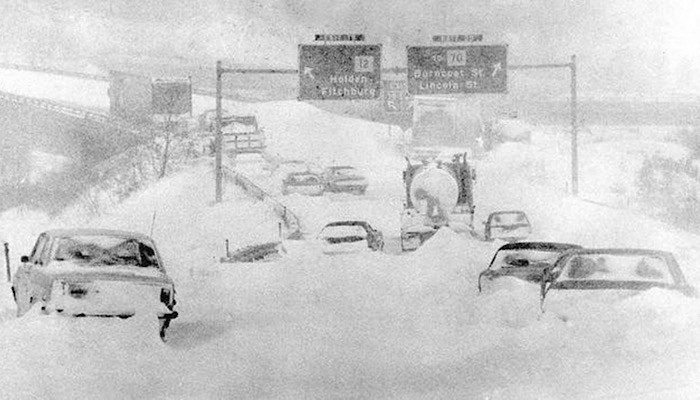

It was risky, but it was the right thing to do. And he respected that. This was in the fall, so I said, I’d start in February. In fact, my first day at Milton Bradley was February 6th, 1978, which was the blizzard of ’78. I blew into town with 18 inches of snow!

And that would’ve been just before a Toy Fair, presumably?

Yeah. They were working toward that; that they were introducing Simon, the lights and sound classic; and Star Bird which was a spaceship that made an accelerating noise when you tilted it up. That was the big deal; we were designing a cardboard base for Star Bird to land on. My boss, John Vernon, drove me home in the snow that first day… We couldn’t see the streets or anybody’s yards or anything. And, you know, John Vernon is still my friend to this day.

How long were you at Milton Bradley?

I worked there for three years. At one point I had 36 games on the market at Toys R Us. And actually, my first game that ever went out was called The Hungry Ant…The first year it was out, I went home for the holidays and visited Toys R Us to look at games for me to play. Back then, their game aisle was floor to ceiling; 10, 12 feet high. You couldn’t reach the stuff that was up high…

So anyway, this woman was standing in front of The Hungry Ant game – and she pulls it out. Now, I’m just a young guy and I’m all excited about having my first game in Toys R Us – and I couldn’t help myself because I’m six feet away. So I said, “That’s a really good game!”

Ha!

She says, “Oh, is it?” And I go, “Yeah. I designed it!” Well. She looked at me like I was – I don’t even know! She was horrified, like I was lying or crazy or something. And she really slllllllllllooooowly slid the game back on the shelf… Then she ran away!

Ha! No?! She… Ha! Why would that be so off putting?!

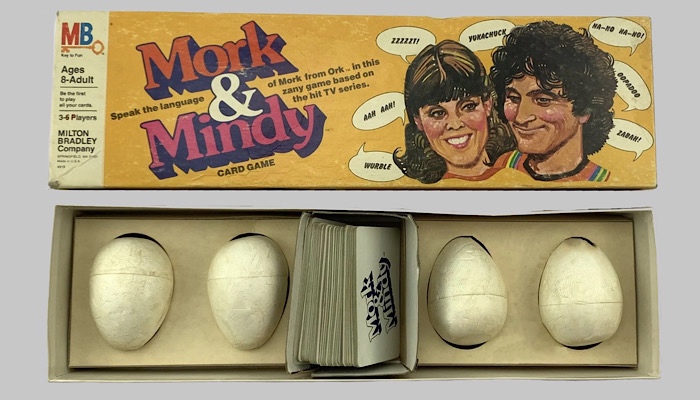

I don’t know! Never worked it out, but it was funny. And I never did that again! Another game that came out around that time – well, ’78; ’79 – was probably the one that sold the most for me – over a million units. It was based on a Robin Williams TV show; it was the Mork and Mindy Card Game. It kind of combined Spoons and Crazy 8’s with some twists.

Twists?

Right. You know, it had a couple of Mork and Mindy twists on proven gameplay. For example, because Mork was devolving into an egg, the game came with four styrofoam eggs. they were flat on the bottom, but weighted off kilter… So they would sit but, with the slightest touch, they’d go rolling around. Then – like in Spoons – there was one egg fewer than the number of players. When someone played a ‘Nanu nanu’ card, you all had to try and grab an egg. Whoever didn’t get one had to say “Shazbut!” and draw two cards.

‘Shazbut!’ being a catchphrase from the show…

Right. Anytime something bad happened to you, you had to say that. If you didn’t, the other players could go “Zzzzzzzt” at you and you’d have to draw two cards like in Uno. So I put this sort of verbal thing in there.

Got it. That looks cute; I love the idea that you go to grab one of those eggs and it’s too wibbly-wobbly to pick up easily. Fun! So you were at Milton Bradley, doing quite nicely for a few years…

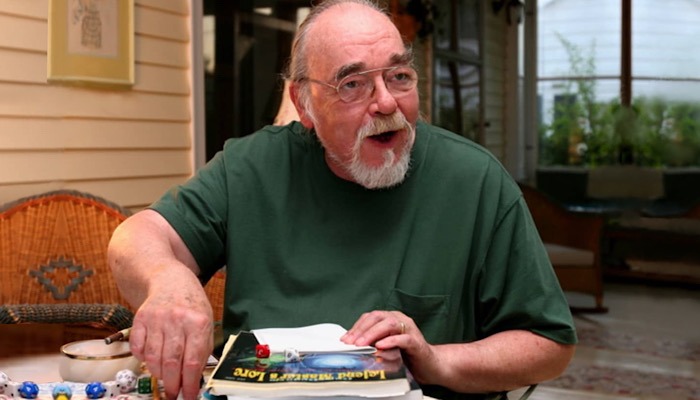

Right. But then I decided I really wanted to meet Gary Gygax, the co-creator of Dungeons & Dragons. So I went to Toy Fair and, when I had some time off, I went found him. For me, it was like meeting Dumbledore.

Ha! And TSR was Tactical Studies Rules which – well… All things Dungeons & Dragons started with them; completely revolutionary.

Yeah, and – you know –here’s this old guy; seems to know everything… I’m still in my twenties, maybe thirty… Anyway, when Gary Gygax said he was looking for somebody to run his design department, I really wanted to look at that. So my wife and I flew out to Wisconsin, where they were based. It was the weekend of the Winter Fantasy gaming convention, and they took me to the basement of this church. There were like 80 people down, all there playing board games. I’d never been to anything like that, and I can’t tell you… I felt like – you know in a fantasy story where there’s one dwarf? He thinks he’s the only dwarf… Then he finds a cave and goes down and there’s all these other dwarfs!

Ha!

I’d never met ONE person who liked to play games as much as me, but here were 80 people who loved to play games as much as me! A lost civilisation of gamers! There was really cool.

You found your people! And presumably, this would be around 1981? When you moved to TSR?

Yes. I co-managed the game design department there. It was an interesting job. It was above the old Dungeon Hobby Store on a floor had a lot of rooms off it. I think it was an old hotel, but it had no warm water, just cold. And there were wasps flying up and down the hallway! Ha! But it was an interesting job; it was fun and I really respected all the people that were there. I developed a Dungeon board game which Dave McGarry invented; I designed the Fantasy Forest boardgame, which ended up being a cartoon and a bunch of figures.

That wasn’t just one role, was it? You had a number of different jobs there?

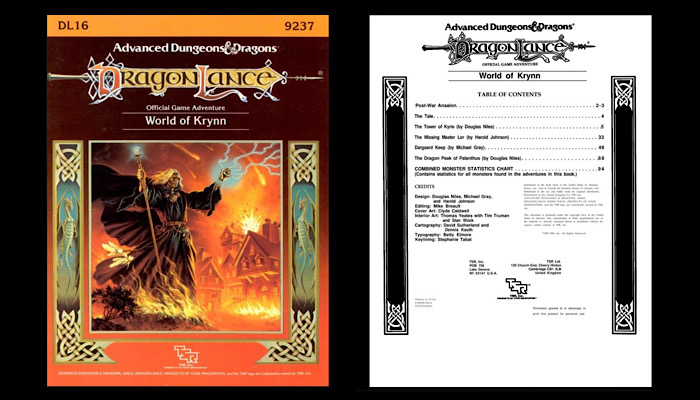

That’s right. I went from being a design manager into marketing briefly, then product acquisitions… I also wrote choose-your-path adventure books – Shadow Castle, and The Lost Wizard. What else… I designed the Dungeons and Dragons module that featured all of the Fantasy Forest characters. I wrote Quest for the Heart Stone, which was an adventure. I drew all the the maps… Jeff Easley did all the artwork for that. And I also wrote about a third of a 98-page book called The World of Krynn…

So anyway, I did a lot of stuff and played games with all the guys there; made friends with people who went on to become brilliant, famous software designers and writers… Some of the most creative people I’ve ever met. In fact, I hired Tracy Hickman; he – of course – ended up writing all the Dragonlance novels with Margaret Weis. I always say hi to him at Gen Con and he always says, “Thank you for hiring me. You changed my life.” So I always feel maybe I did something good.

Well, certainly you did something good– and you did a lot of good things! And on that point, is there a secret to your creativity, Mike?

Well, I don’t think there’s a secret… I think part of it is karma. You know, in Buddhist philosophy, you come to each life with tendencies or potentials and I think that – and this might sound kind of hokey – being in this industry; being in games was just my destiny. I’m the guy who lived and breathed games – and back then it was a very different time…

In terms of the games?

Yes – but everything! We live in a completely new era. Remember, when I started there were no computers. The Apple 48K came along, but there were hardly any interesting computer games or video games. So the world was very different. And I used to say that, with game designers, you have to have it in you. You have to be born with it. Have it in your blood.

So no secret to creativity… It’s destiny for you. And what made you leave TSR?

What I basically think happened is that I went from Milton Bradley – a company that was all businessmen and no gamers – to TSG: a company that was all gamers and no businessmen! So they were hiring anyone: their mailman, their cousin, their grandkids… I exaggerate, but they just had too much payroll for their revenue. As I recall, I was the 110th employee at TSR. They were almost at 400 when they had to trim. They started firing people, 60 at a time. They fired the first 60 – which is a lot. Soon after, they fired another 60… And I decided I wanted to leave before I HAD to leave. They called them ‘The Purges’.

Jesus! The Purges. That’s horrendous. So you jumped before you were pushed?

Exactly. So I started looking; I interviewed at a game-design studio – but they were more interested in TV-promotable, plastic games. I’m not an industrial designer, though; I’m not really a physical mechanism guy. And having an item that moves so it looks really exciting on TV kind of stuff was real important then – often, it’s where the money was, you know?

Yes. The inventor Sally Jacobs describes it as, “Push, push, POP!“, which I think is a terrific shorthand for what you’re describing.

Push, push, POP? That’s neat. Yes… So anyway, I interviewed a few places and they didn’t care for what I’d done. Then I nearly went to Coleco to be a computer-game designer because some of the Avalon Hill designers – Arnold Hendricks, Jennell Jaquays and other people – had gone there to design games.

They offered me a job, pretty much for what I was making, but with a $5,000 sign-on bonus. And I’d moved back to Coleco, which is about 40 minutes from where I used to live; just south of Milton Bradley. I had a week to think about it. And it just happens that I called my old boss at Milton Bradley and told him that I was gonna take a job at Coleco down the highway, so I’d be in the neighborhood.

This is John Vernon?

Right. And long story short: John asked if I’d ever consider going back to Milton Bradley. It turns out that John had spoken to the President of Milton Bradley that morning and he’d said, “We need to get Mike Gray back.”

Wow.

The following Monday, I flew back to Milton Bradley, interviewed with the head of design – and he offered me a job for $8,000 more than I was making at TSR. So I went back to Milton Bradley to do more boardgames.

And philosophically, I think you’ve used a phrase about boardgames that I rather like… Boardgames are “Togetherness in a box”.

Right.

I really like that… I was thinking about it earlier; I think some inventors would do very well to grasp that idea: that what you’re selling is a way to make people connect.

And another thing I like to say about this is that – when you think about games from the perspective of a designer, and as a manager, as a director, a senior director – the needs of everyone who touches a game are vastly different. And it’s really interesting, when you think about the arc of designer to player, how many diverse and conflicting needs there are.

Tell me about that…

The designers want to put out something that’s fun and that they’re proud of. And also – a little bit – they want to impress their peers and their boss. The boss wants the team to create good-quality games on time and on budget. But then they have to go to the marketing department…

The marketing department wants something different…

Right? They want games that are profitable and that sell a lot. So they’re more interested in something where you could sell something for more money than it’s worth. And it has some advertising appeal, or name recognition or something that lifts it above being ‘just another board game’. Then it goes to sales. Obviously, they want games that will sell a lot – and that they’ll get a good commission on.

And that’s a good example of there being – potentially – some conflict?

Sure! It’s not unusual for sales people to not even play games, I mean, back then, once a year they’d get the salesman in and make them play and rate 10 different games – but that’s like a few hours once a year. Meanwhile, the bosses, the vice presidents are interested in the big-business things; company profit, share price and having that magic at Toy Fair that sets their company apart. They want to have THE game; they want to have the product with a buzz – which brings in the people who put the commercials together.

Well, they have their own needs: they’ve got no more than 30 seconds to put the idea over. What do they show? Who do they show? Who do they hire to do the acting? Which parts of the game do they put on screen? All that… Then you go to the actual store buyer. What does the store buyer want? Well, they want something that has recognition. Again, it’s about marketing, and they want to make sure that their square inches are generating profit on the shelf.

Something that the game designer really has no interest in.

And we’ve not got to the consumer yet!

No, we get to them after the purchaser. Because the purchaser isn’t always the consumer. At Milton Bradley, for example, the purchaser – in general – was grandma. She wanted to buy a gift for little Johnny… A gift that made little Johnny think grandma was awesome! So grandma – or mom or dad – has some idea of what the kid’s interested in, and they want to buy a gift that makes them look good and feel good.

And finally there’s the kid!

Yeah. Who actually is the consumer… And in many cases, the parent then also has to suffer through the rules, you see?

I do. And don’t get me started on rules!

The kid might then learn the game and teach it to his friends because it’s good. So in a way, the game designer might only really connect to the final kid. But everybody across the arc of is part of a fascinating evolution.

“A fascinating evolution”. Lovely! You have a very accessible way way of summing things up, Mike. I like the Wizard of Oz analogy; I like your dwarfs in the basement! So… You went back to Milton Bradley in what? 1984?

Yes. And second time around I created Dream Phone, Mall Madness, Omega Virus. The first one was Fortress America. At that time, Red Dawn was a movie that was kind of popular, so I designed this game where the rest of the world invades the United States. To my knowledge, it was the first game where it was three players against one. So not all the players started equally… They started with different geography, and it really was three times the weaponry against one.

This was the game with colour-coded dice?

Right! For the infantry and the mobile infantry, you used a red, six-sided die. And the red was because it was red-blooded humans. Then there was armour… Like metal, so that had a white die with eight sides. Then the aircraft had a blue die with ten sides for the the sky! You put it together and you get red, white, and blue.

Got it. Nice! So you’re putting in some subtle touches with the dice but tapping into the trend, I suppose, of Red Dawn. Was that thinking the result of a calculated thought, though? A deliberate choice? Or something more organic?

Well, for me, it’s always immersive. It’s like I said, game designers aren’t made – they’re born. And the other thing is you have to study… You have to play lots of other people’s games. You have to fill your workshop with tools, with methods and systems and things you need. I do know some designers that don’t play anybody else’s games because they wanna have credit for everything they come up with…

They create in a vacuum…

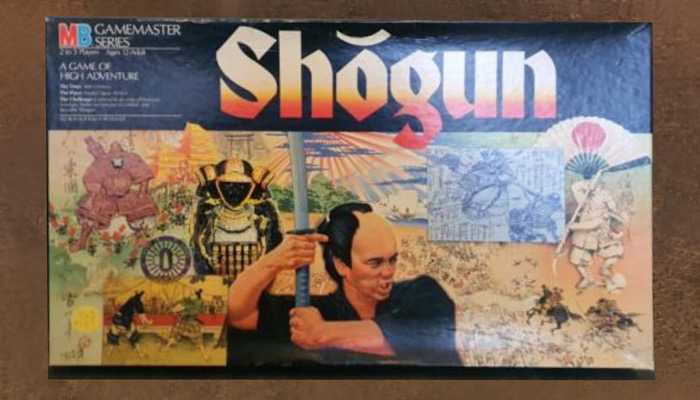

Right. And it’s okay to synthesize; I don’t think of that as stealing. In fact, in the tile-strategy game I did, Shogun, one of the best things for me was how you decide the turn order. I just had it that we were going to draw straws – there were four different sizes. An old idea! But one of my co-designers, Mark Hauser came up with the idea of making them Samurai swords! So when you held them, you’d have four sword hilts sticking out. And I always give Mark credit for it, because having good people play your games can really make your work better.

And at what point, Mike, does Hasbro enter the picture?

Hasbro bought Milton Bradley shortly after I went back in ’84. My memory of it is that Milton Bradley got involved in some electronic game stuff called Vectrex, a vector-based video game. It was a multimillion dollar investment and I don’t think we made money on it. And I think Hasbro more or less came in around then and saved us… For the most part, they left us alone; we got on with our own stuff. Later, they also bought Parker Brothers and Kenner which was mostly toys.

Anyway, they started out running Parker and Bradley separately: separate design staffs, separate sales staffs, separate marketing staffs… But that meant we competed for retail dollars, so later on they combined it all into one. Of course that saved a lot of personnel – but the diversity of product went way down. I think the idea was they wanted to do more with less; to have brands instead of items. But I think it was toy thinking, not game thinking.

In what way?

Well, this is just my opinion of course, but I think that game players would rather have a new game than another game. Meaning I’d personally rather have a brand new play experience than another version of Monopoly, or a silver and gold Connect4 or what have you. For me, I think a new experience is more important. This is just how I feel about it, and it’s worth saying that some of the things I’m relating to you are from another age!

Oh, of course. I think people understand the context in which we’re speaking… We’re talking about your career – you retired 10 years ago: games are different, the market’s different. I think people reading this will see it as your perception based on your experience at that time.

Right. And as well as the market and nature of games changing since then, we’ve also had the blossoming of cooperative games and tabletop games and Euro games. It’s a different world now than it was then.

Right. Even our perception of what makes a game good is different now to what it was back then.

Absolutely. I mean, back then we might have been seen as some sort of pioneer designers, but now… Boy, I can’t hold a candle to the people who are designing games today.

Well, I don’t know about that… I’m quite sure, though, that they’d say that they couldn’t do what they do now if you hadn’t done what you did then.

Well, thank you.

And following that point, Mike… You won the I.D.I.O.T. Award at the UK Inventors Dinner. You won it in tandem with Mike Hirtle, did you not?

Yes. Mike Hirtle was my boss – one of the smartest guys I’ve ever met. If I ever did a quiz show and had to phone a friend, I’d phone Mike. He’s just a encyclopedia of information. He’s really, really smart about a lot of things.

Well, he spoke very highly of you as well; asked me to pass on his very best regards. Do you remember how it felt to win the I.D.I.O.T.?

Oh yes! I remember I was very proud… Because I knew the reputations of the other men and women who were I.D.I.O.T.s, you know? It was a real honour to be elected into that group of people. And those events where the I.D.I.O.T.s got together were the highlight of the year. All the British game inventors, designers and companies came together for a big dinner… And you got to talk to so many people that you admired. And then Mary Danby would do her questions and answers: A or B, put your hands on your head for A, on your behind for B. You’d have to sit down if you got it wrong. Great fun.

And commerative, of course!

Right. And I think one of the greatest compliments in a game designer’s life is to have someone come up to you and really know what you did, and know what was good about it. That’s really much better than a casual or flattering comment. So I always tried to know what people had done, and to play their games and then be able to go to them and tell them what I liked about it. It’s sort of validating. Do you know what I mean?

I absolutely do know what you mean… To sincerely reinforce a person’s esteem, or approbate their worth, can be a very small gift – but it can have a huge meaning.

Right. I’d try to do that. I’d try to validate people.

Well, I agree with you, Mike… And to that end, perhaps it’s worth my saying that you should know something about your own career. I think you should know that – even 10 years after you’ve retired – people still talk well of you, they talk well of your games, and they talk well of your contribution to the industry.

Well… Thank you. Thank you very much. That makes me feel good. I look back on my career, and even the retirement parties that different people held for me with… Well. I cherished them: the kindness they put into those events will be with me forever. And I do like to think that, in my own quiet little way, I made the world a little bit better… I made millions of people smile and enjoy being together.

Perfect. Let’s wrap things up there, Mike; it’s been more than a pleasure to tie in with you, my friend.

Thank you.

Nanu nanu.

–

To stay in the loop with the latest news, interviews and features from the world of toy and game design, sign up to our weekly newsletter here