Keeping the bar high in licensed toy design

Say it quietly, but I have worked in licensing for over 25 years now. Long enough to see Woolworths disappear from the High Street and to see Amazon arrive on our doorsteps.

It has been a period of dramatic changes but in some ways things haven’t changed greatly. The process and business of licensing remains essentially the same. At the heart of it is engaging and commercial content. It is a selling and buying business.

Despite the passage of time the toy and licensing businesses remain intrinsically linked. Many Intellectual Properties (IP) that are used in licensing were, and are, sourced from the toys and game industry.

When I started in licensing, My Little Pony was a popular licensing property and one of the first deals I was involved in was developing the official comic based on the brand – I think you can still buy the comic today (updated of course).

My Little Pony remains a popular licence, with eye-catching partnerships with the likes of fashion brand Moschino. Indeed, some of the My Little Pony consumers from twenty years ago are still consumers today – the difference is they now tend to wear the brand rather than play with it. Check out your local Primark – toy brands are now lifestyle brands.

Brands like My Little Pony are now managed as franchises with long-term plans involving big scale activity like movie releases; but to succeed and survive they need committed licensees and a regular programme of fresh product. Licensing allows IP owners to access new ideas, innovation and tap into developing markets.

Effective IP owners create a forum for licensees to innovate by providing collateral like style guides and showing flexibility to ancillary rights in associated categories. Dress up is a good example of a toy category succeeding for toy brands through licensing. Companies like Rubie’s know how to make the most of a toyetic licence. There is a value in being a specialist.

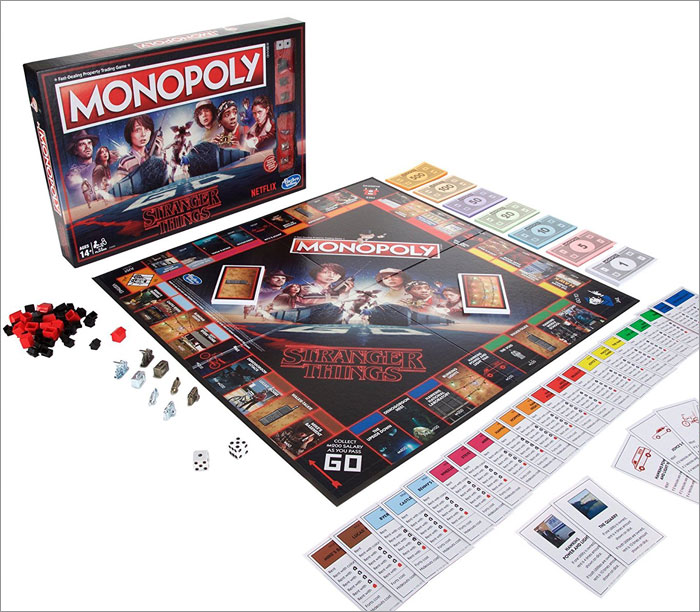

Other toy brands that have prospered in the licensing sector over the long term include Monopoly and Cluedo. The gameplay at the centre of these brands’ DNA lends itself well to sales promotion activities in particular – think McDonald’s promotions and Lottery scratch cards. Not all licensing is centred on children’s products and indeed this is one of the changes I have seen with more toy lines developed for older consumers.

Interestingly Monopoly has been a brand that has developed a significant new string to its bow through licensing.

With input from Winning Moves, Monopoly has spawned ranges of special editions featuring brands like Star Wars and Beano and into sectors like football with club editions. This is an example of a trend in toys and licensing for more custom products as consumers seek bespoke products to celebrate their fan passion.

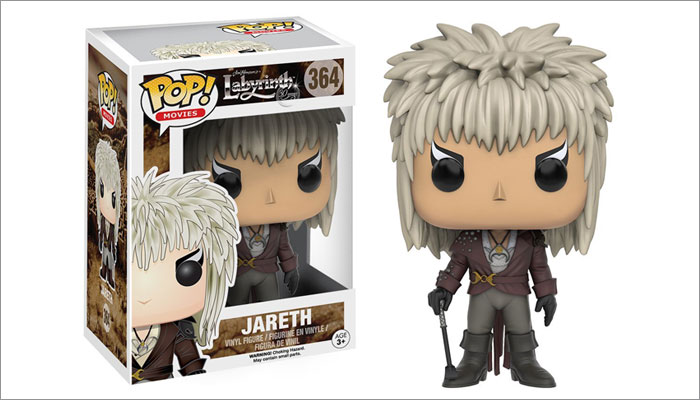

Licensing is more switched onto personalisation, limited editions and fan based products generally. The success of the Funko brand, built on collectible Pop! vinyl figurines, speaks to this. They are also a company that has recognised that toy consumers can be adults and that collectability is a purchasing driver.

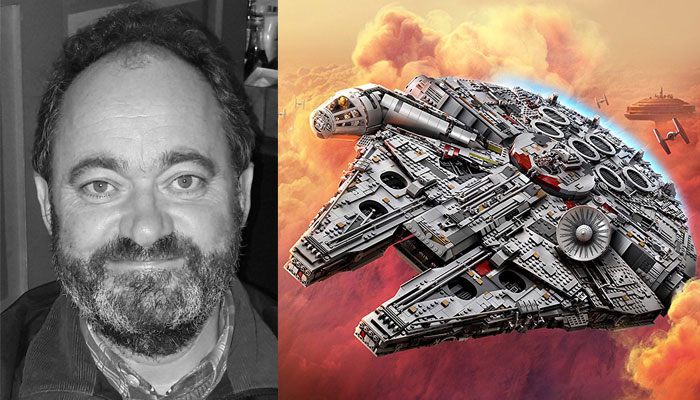

Related to this point is the rise of pocket money collectibles. Years ago collectibles tended to be centred on sticker and trading card collections. Today, brands such as LEGO and Shopkins have shown there is great potential in collectibles sold at pocket money prices in blind bags. This is often a stepping off point for consumers to buy into other toys and games.

However like many successful categories in licensing, the toy and licensing companies need to make sure they don’t overfish this sea. It is easy to kill a category. Consumers seem savvier these days and social media allows everyone to become a product reviewer. Campaigns and product development are more focused on consumers and there is a greater analysis of markets. Gut feel seems less prevalent these days.

Another key change I have seen is that IP owners are more involved in the creative process these days.

One of our clients, Aardman, spends a lot of time on developing toy and game ideas for brands such as Shaun the Sheep and Wallace & Gromit. A combination of techniques are used including in house design development, direct work with factory suppliers to create prototypes, commissioning toy inventors and also listening to fans.

Aardman used a crowdfunding campaign to fund new animation for their iconic Morph character. This has encouraged them to look at this route for toy and game developments not least as it creates an instant consumer market for a product. This is associated with the fact that it does seem more challenging to get new products into retail these days. Crowdfunding and fan communities can help create markets.

There also seems a lot more awareness of the value in specific product development linked to licensing and a real effort to avoid shortcuts. Whilst there are still examples of poorly designed licensed products, it is much less common now and old school label slapping is generally frowned upon. We need to keep the bar high in design and innovation terms.

I expect to see crowdfunding being used more often in a licensing context not least in the realm of archive properties. Thinking of TV and film properties from the Eighties or Nineties, this may be a route to market for them and a way for IP owners to gauge their commercial appeal without over committing. Activating archives could be a good new source of revenue for IP owners and a creative resource for toy companies.

The toy industry has also been an important outlet and benchmark for licensing programmes. Many other product categories in licensing look to the toy category to lead the way. They will wait to see if a master toy deal with a ‘big’ player has been signed. There is a logic to this in that toy companies can create significant momentum for a property via their marketing, distribution and sales reach.

However toy companies can’t support all properties, especially in already crowded areas like pre-school, and these days there is far more supply than demand. I think licensees may need to adjust their thinking and not wait for a toy company to lead the way. This ‘wait and see’ approach has, at times, slowed down the growth of new properties and stifled creativity.

Rights owners may also need to look beyond toy companies to kickstart their licensing campaigns. This is partly due to market dynamics but also economics as toy companies have recognised the value of IP and are more likely to focus their efforts on their own brands – particularly those that have adopted the franchise model.

This could, and should, leave room for a new generation of toy companies who could use licensing as a way of achieving growth both for their own IP – where licensing gives access to multiple partners – and buying an IP – where licensing can allow smaller companies to compete with bigger players. Companies like Moose and Spin Master are good examples of this.

As a moderately successful racehorse owner I learned a while ago not to make too many predictions (if you think licensing professionals have a book of excuses go and talk to a racehorse trainer – they have several books). That said, one prediction I would make is that successful licensing programmes will always start with IP that is original, engaging and motivating.

But programmes that manage to work with capable partners who can bring those ideas to market with products that consumers really want – across a broad range of retail channels – will be the most successful.

Licensing is a business that relies on and welcomes new ideas, new companies and new opportunities.

Ian Downes is director at Start Licensing, an independent brand licensing agency.