Prolific designer Raf Peeters discusses how he creates so many ideas for SMART Toys and Games

Raf, pleasure to meet you. I’m curious to start with a question I suspect I know the answer to… With which toys and games did you play growing up?

During my childhood, I spent most of my time playing with toys and games I crafted myself. My dad and I once built a wooden castle together in our backyard. It was spacious enough for me and my friends to play inside. Much of my youth was spent there, pretending I was a knight.

I had a feeling it was going to be imagination based. No commercial toys?

The only commercial toy I extensively played with was LEGO. I once thought I had a sizeable collection, but it pales in comparison to what my sons own today. Not that this was ever a problem! I believe that the limited number of sets forced me to be more creative with what I had. I also loved mixing and combining LEGO with other toys like wooden blocks or railway sets.

Great! And later, as you got older?

As I grew older, my holidays were often used to create boardgames. Most of them were played only once. The next holiday, I preferred starting with something new. I always found more joy in making games than actually playing them.

Sounds like you were heading down this career path from a very young age! How did you actually get into the industry?

In my last year studying product design university, I had to choose my own graduation project. Naturally, that had something to do with toys. To help with their projects each student needed to find an external mentor from the industry. That’s how I met one of the founders of SMART, the company I still work for after 27 years.

So 27 years on, you delightedly remain a product developer and inventor at SMART Toys and Games. Dare I ask how many products have your fingerprints on them?

I’ve invented and developed 130 single-player SmartGames so far, with around 80 still in production. Most of these puzzle games were designed together with my friend and colleague Leighton Rees in the UK. In the past, I also created many products for SmartMax – a collection of magnetic construction toys; SmartWood – preschool wooden toys, and SmartFrames – metal wires and beads for toddlers.

I imagine this will be a difficult question but – just to orient our readers – what are some of your favourite products to have worked on?

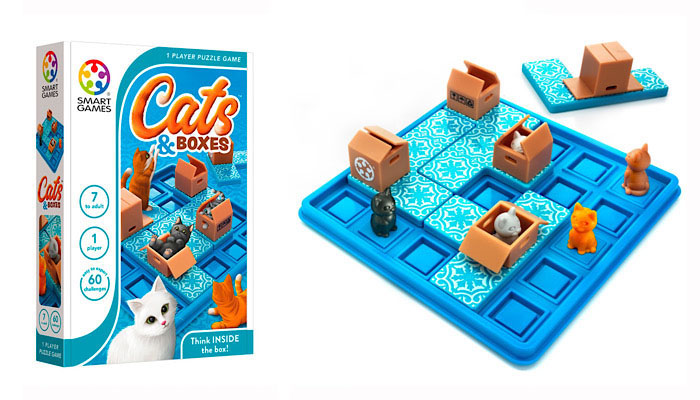

That changes from time to time but, at this moment, my favourites are Cats and Boxes, Camelot JR, Jump In’, Bunny Boo, Temple Trap and Safari Park JR. But most people will be more familiar with one of the many IQ-puzzles I designed for SmartGames, like – for example – IQ-Fit or IQ-Love.

Fantastic. And, broadly speaking, what makes an idea right for SMART?

That’s an interesting question that either needs a very long answer or a very short one. The short answer is that the idea needs to have the potential to result in a quality product that is so good – in every possible definition – that it can be played with for many years. So we’re not interested in short-lived products, the most recent craze, or toys with a gimmick but no real play value.

There are few things that make better tools to play with for a young child than sticks and stones, mud or cardboard boxes. So whatever we can come up with as toy designers needs to do better or at least equally well. Surprisingly, many toys make great gifts, but are very poor tools to play with…

“They’re very poor tools to play with”. What an interesting choice of words! Just expand on what you mean there…

Well, this is probably why so many toys quickly end up collecting dust. You don’t buy a hammer to hang it above your work bench, do you? You buy it to use it when you need to fix something. In the same way, a toy is only good if it’s really being used as a tool to play with. So a toy should create as many options to play as possible; options that wouldn’t be there without the toy. And the longer a toy can be used, the better value for money it offers.

That is absolutely brilliant. I honestly wish everybody in the industry could read what you’ve just said; it’s brilliant. Alright, let me see… I the nature of many products at SMART exists somewhere on a spectrum between brain-teasing and brain-melting! Typically, how does an idea come together?

Most people think that you begin with a game concept and that the theme and design is applied to it later, like some kind of secret sauce to make everything more attractive. Although this might work, I feel that for products developed this way, the design is an afterthought and there’s often a mismatch between the game mechanics and how the product looks.

I can see that; I think that’s true more often than people would like to admit.

In most cases, I work the other way around. I start with something I find visually attractive, something that’s iconic, or a theme I find engaging. This theme should have enough potential to turn it into something recognisable, iconic and at the same time distinctive. A great puzzle concept that doesn’t have any possibilities to turn it into something visually striking will never be developed into a SmartGame by me, no matter how interesting the challenges are…

But the theme should also support the game rules or the object of the game. I don’t know much about it, but one of The Four P’s of Marketing is still ‘Product’. The product itself should communicate what it is and how it works. The right theme can be very helpful for this… Take, for instance, our puzzle games based on fairy tales: Three Little Piggies and Little Red Riding Hood. In both games, when you tell in short what happens in the fairy tale, you’re basically explaining the goal of each game.

So there’s almost an intuitive connection…

Right. And once I have this image in my head, I try to come up with a game mechanic that fits. Also, when people see any product I make, their first reaction should be that they want to touch it. I don’t always succeed, but my best work definitely has that quality – I hope!

Yes, most of SMART’s products are irresistible… And they don’t disappoint either – they usually give a pretty terrific tactile experience. So you like to start with an interesting theme. How easy is that to do?

Ha! Finding an interesting idea is the part of my work I really hate! People always tell me that I shouldn’t complain because I come up with five to eight games every year. But there are 365 days in a year which means that at least 357 days are frustrating for that part of my job.

Ha! That’s the way to look at it!

That said, I really love the next step in the development process… Working out the details, finding the best combination of puzzle pieces and game rules, selecting the right challenges and so on. My motto is ‘always to try to do more with less’. So I keep fine tuning a concept until only the essential that is needed to make a good puzzle game remains. But it’s not seeking simplicity for the sake of simplicity…

For SmartGames, using simplicity has a long list of benefits. Simplicity also doesn’t mean that the challenges are simple to solve. Sometimes, a few well selected game rules and the right set of pieces can result in complex game play. The biggest challenge when designing SmartGames is solving that contradiction: how can you make something with only a few parts and game rules, but still create 60 or more challenges from easy to difficult, that offer enough variation to stay interesting.

What’s the next step, Raf?

Next, most of the visual design is done together with my colleague Leighton. He’s a pro in the design software SolidWorks. Then, once I’ve found the best possible set of pieces and game rules, another colleague writes an algorithm to generate challenges. Don’t think this makes the process of creating the right challenges effortless, though! You can often choose from hundreds or even thousands of challenges – but most will not be very interesting.

So, in a way, the algorithm can give you too many options? You have to cherry pick the most interesting?

Exactly. So it takes a lot of time to find a balanced set of challenges for each game. I take pride in the fact that I also playtest every game completely – sometimes several times. When the design of the physical game can be compared to hardware, the challenges themselves are like the software… And both need to be excellent to have a quality product.

This is absolutely fascinating to me… Let me ask you this: how much of your creative process is an art, Raf? And how much of it is a science?

My wife and oldest son are artists. My wife works in ceramics, and my son in paper – origami. But I don’t consider myself an artist or a scientist. I’m really a product designer in the core. I like the limitations of creating a functional product, one that needs to be safe and produceable for the right price and so on. And I like the challenges that come with the fact that it needs to be sold afterwards… If possible, in big quantities! It’s all those criteria and limitations that force me to be inventive and make this job great. I’d hate it if I had carte blanche to create whatever I wanted.

How do you stay creative?

If you mean, how can I keep creating – that’s no problem! It’s in my nature that I want to create new things. If you mean how can I create things that other people find original… There I would say that ‘being original’ is not a goal. It’s a means to an end. If you can solve a product problem in a different way than usual and this results in a better product, I love being original. But if it’s only different – but not better – I prefer to stick to something that’s tested and proven. I made the biggest mistakes in product design was when I tried too hard to be original.

On the other hand, ‘original’ can be a very valuable quality of a product. And the fact that nobody has tried something before doesn’t necessary mean there’s no other or no better way to do it. The only way to find out is to keep on searching, thinking, trying again and again and mostly failing. Like I said earlier, I don’t really like this part of my job – but if you don’t search, you’ll never find anything. And the next steps in the development process are so much more rewarding if you can work on your own ideas.

I like that you’ve identified that trying too hard to be original was a mistake. Let’s talk about the other side of the coin, then… What do you think prevents creativity? What’s your kryptonite?

The first years I worked for SMART, the biggest mental block was my misconception that each new product needed to start with ‘a big idea’. Later, I learned that, often, the combination of smaller ideas – ideas that, at first sight, may not seem very special – can lead to equally good end results.

And these days?

These days, the biggest hurdle is to find something where I can surprise myself! After 130 SmartGames, there’s not that much I haven’t tried within the limits of what a SmartGame is. Experience can make things easier, but I don’t necessary want to have things ‘easier’. You can only grow if you encounter problems that require you to learn new things.

Brilliant. I’m enjoying this immensely, Raf. We do need to start wrapping things up but I’m curious… I can’t imagine you have much time to be inventive outside the industry. What else have you designed, though?

If I wasn’t a product designer, I’d probably be an architect or interior architect. So I liked working on the layout of my garden and house, and I designed a few things like my kitchen and a cabinet in my home office. For some reason, everything I design outside the industry still looks like a puzzle.

Ha!

Also, around 15 years ago, I designed big ‘playing furniture’. My kids have used it intensively for years, so from that point of view it was quite successful. I think that there was a gap in the market for such a thing… But there probably was no market in the gap. It would’ve been to big and expensive to sell, so I never found a company to produce it.

You have some terrific aphorisms, Raf. Alright! Last question: what’s the most interesting thing in your office or on your desk?

My home office is almost completely empty! It’s a necessary counterbalance for how my office at work looks like – which is chaos, not created by me! So I would say that the most interesting thing in my home office is the view through the window. In terms of a product, though it would be a small wooden car.

A wooden car?

Yes. I got it many years ago as a gift from a Danish designer that I met at the Nuremberg Toy Fair. He created simple but beautiful toys that were more original than the usual wooden toys you see there. Unfortunately, he went bankrupt after a few years. It’s a constant reminder that success not only depends on creating good products… You also need the right people around you to work with, and you still need to have a bit of luck to have the right product at the right time and in the right place.

–

To stay in the loop with the latest news, interviews and features from the world of toy and game design, sign up to our weekly newsletter here