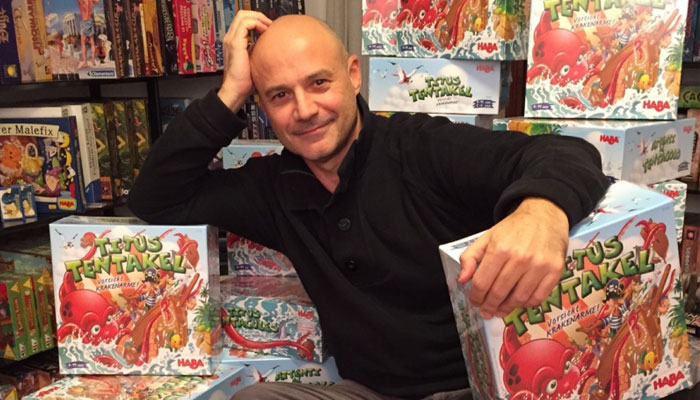

Prolific game designer Leo Colovini talks design, creativity and his most underrated title

Leo, it’s great to speak with you. To kick us off, what set you on the path to a career in game design? Was it always part of the plan?

I was 11 years old when I started playing chess in a chess club in Venice. One day, one of the members of the club – a strange gentleman with a French “R” who looked a little bit like Einstein – came to the club with a wooden box. It contained a chessboard and some strange cylindrical chess pieces, with the design of the piece in the two colours on the two ends.

He began to explain the game to us: it was a hybrid between western chess and Shogi. When you captured a piece, you could turn it over and in a later turn put it into play as your own. The name of the game was Mad Mate and the gentleman with the lisp was Alex Randolph.

Ah! The iconic designer of games like TwixT and Enchanted Forest.

Yes – it was a shock… Is it possible to invent games? Does anyone actually invent games? As a child, I loved playing with board games and I also loved modifying them, rebuilding them, inventing new ones. I often used LEGO to create three-dimensional prototypes. So when Alex invited me and other members of the club to go to his studio for playtesting, I accepted the offer with joy.

Amazing! What an introduction to game design!

Those long afternoons in Alex’s studio testing his games were very educational. I learned how to create a prototype, how to test games, how to fix their flaws… But I didn’t just try Alex’s games, I also tried to propose my own ideas to him. At the beginning they were very wacky ideas – I was still a child! – but Alex sensed that there was creativity and talent there and encouraged me, explaining what could not work and what was good.

A few years later I finally brought Alex an idea that he found interesting and associated with a mechanism of his own. Hence, Piratesque – a title proposed by my mum! – was born. Alex made a beautiful prototype with two types of wooden ships and a beautiful map.

Did it ever get come out?

He took it to trade fairs but could not find a publisher willing to publish it. That was the first disappointment – the first of many, because if you want to be a game inventor, you must first have tenacity and never give up. A few years later, however, the two elements of the game were published separately: one in Die Magische 7 and one in Spion & Spion.

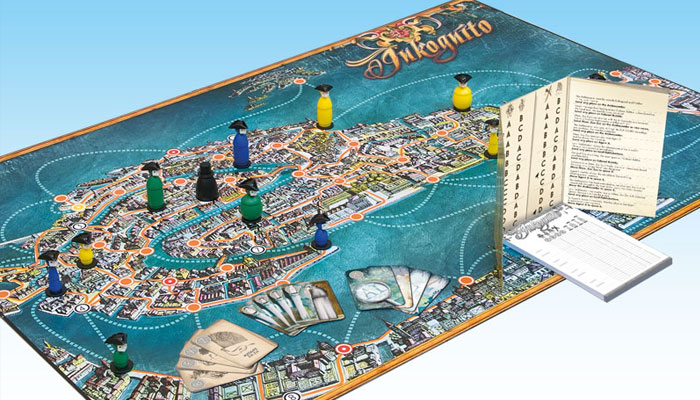

After that experience, I proposed another movement mechanism to Alex based on the creation of rainbows. Drachenfels was born and it was my first published game. From there it was a short step and two years later we developed Inkognito together.

I love that you were mentored into the industry. Great story. Now, you’ve been designing games since 1987. What’s been important to you achieving longevity in this industry as a designer?

I think my greatest strength is to always create something new and different from my previous games, spanning genres and game types.

On that, what starts the design process for you? Do you begin with a mechanic, a theme idea, or a different leaping off point?

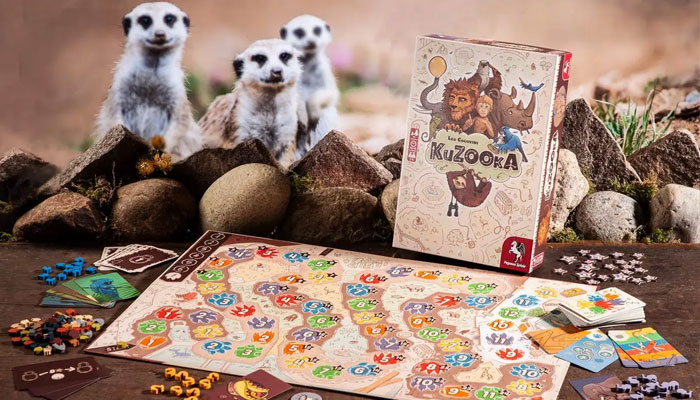

I don’t have a standard process. In most cases I start from a mechanic, but sometimes from a theme. In other cases, I start with the idea of turning something well-known into something new, like in KuZOOkA, which is basically the cooperative version of Liar’s Dice.

I’m glad you mentioned KuZOOkA. This launched last year and has had a great reaction. So this started with the idea of expanding on Liar’s Dice?

The first step was actually made by my partner Dario. Being a keen poker player, he developed a version of Perudo with poker cards in which you always have to raise with a better poker combination than the previous one. Trying out that version of Perudo – very fun, by the way – I told myself that it was still a bit too similar to Perudo to be published… So I thought about how to revolutionise the system and decided to try to create a co-operative game from a game based on continuous challenge – and so much interaction between players!

You’ve collaborated with lots of designers over the years. What is the key to a successful design collaboration?

It takes mutual respect, listening and humility in recognising when one’s own ideas do not work and when the partner’s proposal is an improvement. But in general, I really enjoy collaborating with other authors.

By the way, we have very often the chance to collaborate with many designers because we organise the Premio Archimede. A lot of very good ideas come from the participants to the Premio Archimede and sometimes, when I see that a very fresh idea can be developed and joined to other ideas of mine, I propose to the author to collaborate.

We’ll put the link to the Premio Archimede competition here so people can check that out here. You’ve also pitched to plenty of companies, and I imagine they have different ways to working with game designers. How do you approach building relationships with publishers?

Perhaps the most beautiful part of our job is the network of relationships we build over time with the different publishers. In many cases they are dear friends, not just business partners. That’s something I really appreciate in the game industry. Even among publishers there is no envy, no rivalry, no jealousy. You are all part of one big family.

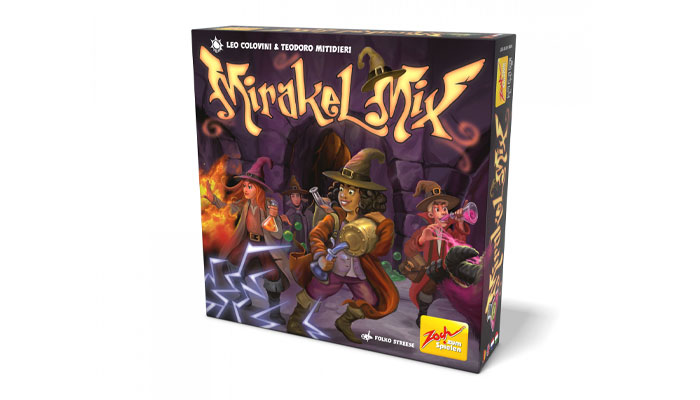

Absolutely. I wanted to disucss another one of your games – one I saw at Spielwarenmesse earlier this year – Mirakel Mix, designed with Teodoro Mitidieri. It had great table presence, and I liked the interactive between both sides of the board. How did this one come about?

Teodoro, many years ago, came to us with the idea of a barrel from which balls came out randomly, the contents of which could be varied by the players themselves. From that idea we developed various games, but only recently with Mirakel Mix did we come up with the right idea to exploit that beautiful mechanism – and so we developed Mirakel Mix together.

Teodoro often has very fresh and original ideas that rarely work, so he occasionally comes to see us – or participates in the Premio Archimede – and so we see what is good and decide together how to develop it. A very good joint venture!

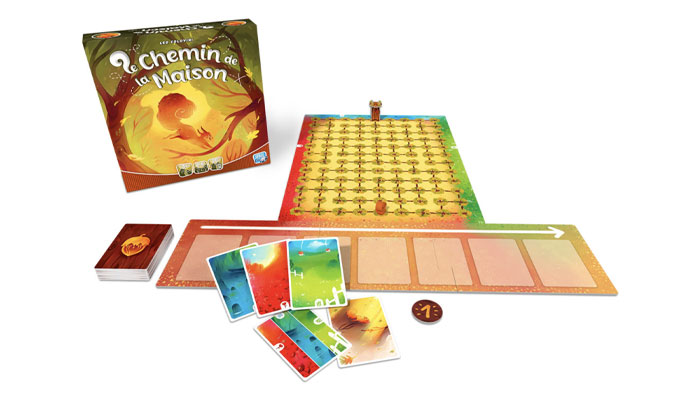

It sounds it; the game looks great. Now, another new title of yours is Le Chemin de la Maison – or Crossing the Woods – from Space Cow. How does this one play?

It’s a cooperative children’s game. The idea is that the turn player draws a card and can only choose where to place it on a board from which the cards will then be revealed in a specific order. So the player does not get to decide which card to play, but tries to make sure that the card is played before or after the others – depending on whether he thinks it’s better placed before or after.

The cards are then revealed and played in an order based on the position where they were played, not the order in which they were played. This sometimes leads to great strides toward the goal, or sometimes to wasting a lot of cards for nothing. Players win if they can get the squirrel to its home before they run out of cards.

Now, before we wrap up, I wanted to ask: What is your most underrated game and why?

Good question… I’ve published 105 games at the moment, and some of them are underrated – for example Alexandros, Dschingis Khan and more recently Santiiba. Why? Probably because I made too great an effort to introduce original elements… Sometimes when a game is too original, players can get a little bit confused.

We’ll call them ahead of their time! Last question: What helps you have ideas? What fuels your creativity?

Life! I look around, I read, I try to absorb as many stimuli as possible and this, sooner or later, triggers some ideas.

Leo, a huge thanks again. Hopefully we can tie-in again soon.

–

To stay in the loop with the latest news, interviews and features from the world of toy and game design, sign up to our weekly newsletter here