The real deal: How likeness rights can make or break a toy line

Many years ago I was the ‘head’ Power Ranger in the UK – fortunately lycra wasn’t the compulsory workwear!

The Power Rangers were owned by Saban and I headed up their UK team. We worked closely with Bandai who were the UK master toy licensee. They were a great toy partner: proactive and good communicators. In fact they still are the master toy partner – a great example of longevity in licensing.

Toy sales were good. However, there was one thorn in our side: one or two retailers chose to sell what I would describe as a ‘lookalike’ Power Ranger alongside and often mixed in with ‘our’ range. I think the range was called something like Space Rangers. We tackled the retailers about this.

Our approach was why stock a product that isn’t the ‘real thing’? They weren’t convinced citing choice, price and diversity. We remained sceptical.

To counter this, we undertook some research with Power Rangers’ consumers and viewers with a focus on their opinions about the Power Rangers. A theme emerged: consumers loved the Power Rangers, recognised them and valued Bandai’s toy line. They looking forward to Bandai’s new toys and recognised the ‘real’ Rangers.

Conversely they felt ‘Space Rangers’ was not the real deal and less appealing. We shared this research with retailers and gradually they moved away from stocking the lookalike item. For me this was a victory for the power of the brand and deserved recognition of the value of licensing.

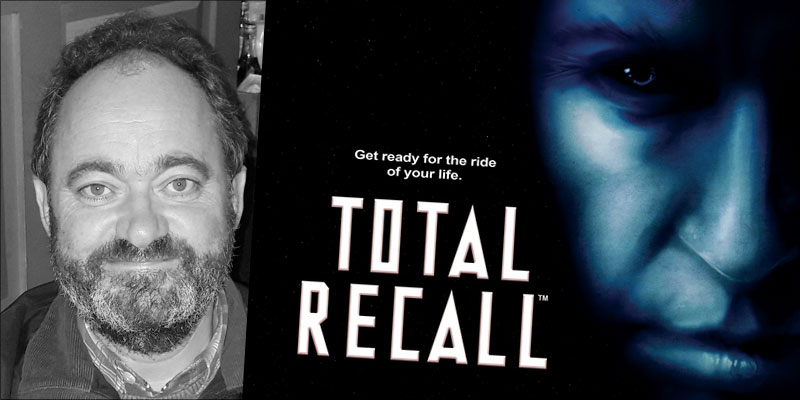

So in the context of this experience, I wasn’t surprised to read that Overworld Games put their funding shortfall for a Total Recall game down to the fact that they weren’t able to feature images of the actors or stills from the film and were forced to use commissioned art instead. To be fair, Overworld Games held the official license for Total Recall and acted 100% correctly licensing-wise. However, despite best efforts, they weren’t able to secure likeness rights.

The copyright holder probably had their hands tied in regards to these rights as they were working with talent contracts that placed restrictions on their use. These contracts were drafted some time ago and are not necessarily reflective of modern business outlook.

I suspect this will be an issue with many ‘retro’ film and TV properties. Accessing likeness rights is still an issue today but I think less so as production companies and cast members are more aware of the potential for merchandising. Most often cast members will participate in revenues. Rights holders should be building a model for the future which will allow full use of likeness rights, stills, and voices and so on. A successful merchandising programme can help promote and sell a film. It can help build a legacy. Star Wars is arguably the prime example of this.

Returning to films like Total Recall that are subject to restricted rights usage, it is difficult to see what else Overworld could have done. My general advice would be to try to incentivise the copyright owners and actors with an ‘enhanced’ deal. By this I don’t mean offering more money. I would look at how the initial concept is presented, perhaps investing in a video ‘sales kit’ that can be viewed by all parties – hearing the story second-hand can be less impactful. Focus on non-financial ‘upsides’ such as creating a platform to communicate with fans extending the life of a property.

In the case of the ‘talent’ may be look at profile building activities such as fan conventions, social media exposure and potentially a pathway to further alliterations of the franchise. For some talent this kind of activity can be a useful second income and also open up new opportunities such as involvement in sequels. Maybe look at ways to involve the cast in the development and promotion of the product. A contributor role might be attractive. These ideas should be put forward as early as possible in the pitch process.

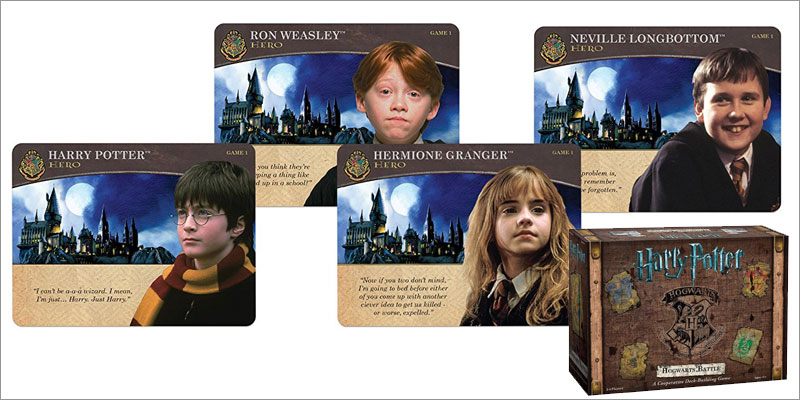

My view is that consumers expect to see the real stars of a show or film in and on products. We have a generation of consumers who are now merchandise savvy and have grown up with franchises like Star Wars and Harry Potter that feature their heroes and heroines. That is probably the gold standard. I would recommend making this a prerequisite of NPD – and an early question in the deal discussion. Arguably, if as a games company you can’t secure likeness rights and stills, it is best to move on. The end product is likely to be less appealing.

The issues associated with Total Recall will not necessarily apply to all ‘old’ films and TV shows, but you should check this as early as you can in the acquisition process. The rights holder might be able to help particularly if you can outline the contribution your genre or toy range could make to franchise building.

Rights holders are keen to find new sources of revenue and to activate their rights archive. They shouldn’t stand still in this matter. It should be worth their time and energy getting their IP game ready. They should engage with talent in a proactive way.

Licensing the right rights has a real value.

Consumers are looking for an authentic experience. Going back to my Power Rangers experience, one of the retailers who didn’t ‘go go Power Rangers’ is no longer in business – may be the real Rangers had a value after all.

Ian Downes is director at Start Licensing, an independent brand licensing agency.