Rob Daviau sheds light on the collaborative design process behind Pandemic Legacy Season 2

‘Tomorrow’s games today’.

That’s the line which greets you if you head over to games designer Rob Daviau’s website. In the hands of some, it would perhaps simply function as a nice thing to stick on a business card, but Daviau’s back catalogue of innovative games can actually back it up.

He started his career in games design at Hasbro back in the late Nineties, working on licensed titles like Risk: Star Wars, Lord of the Rings Trivial Pursuit and Cluedo: Harry Potter Edition. While on paper, these kinds of projects might not be seen as exercises in flexing one’s creative muscles, Daviau managed to pack in mechanics that meant these were more than just branded re-skins (you can actually die in Cluedo: Harry Potter Edition).

But Daviau is likely best known for introducing the Legacy concept to the world of games. It struck him in 2008, when, in a brainstorm for Cluedo, he stated “why do we keep inviting these people to dinner; they just keep murdering people?”

And so the bones of Legacy was unearthed: games that morphed and changed as you played them. New rules come into effect, cards are ripped up, a shifting narrative ensues and actions actually have consequences; some temporary, some permanent. In what remains a fairly radical concept, these games have a beginning, a middle and end, but an actual end; you physically alter your copy of the game so you can only play through it once.

While the idea of a Cluedo Legacy game was shelved by Hasbro (the campaign to bring it back starts here!), the firm later embraced the idea for a different brand: Risk.

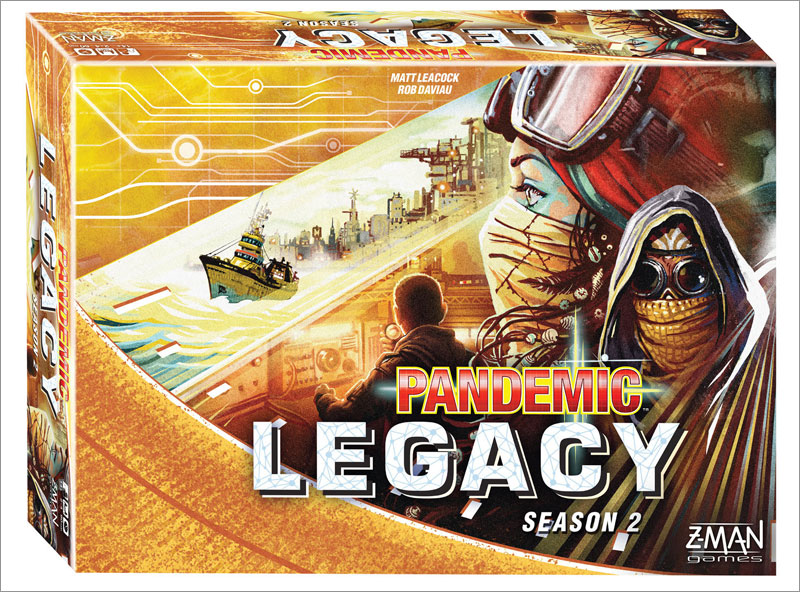

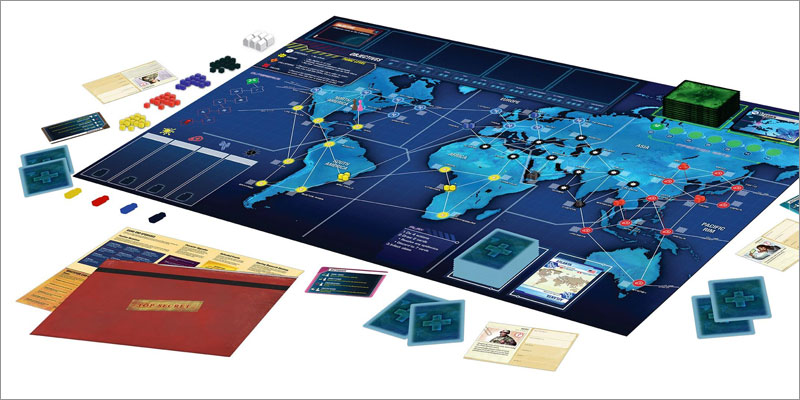

Shortly after Risk Legacy launched to rave reviews in 2012, Daviau left Hasbro to embark on a career as a freelance games designer. In 2015, he teamed up with Matt Leacock to launch Pandemic Legacy Season 1, deemed as one of the greatest games of all time and the title which truly cemented Legacy as one of the most innovative concepts to shake the world of board games in many a moon. This was followed by SeaFall last year, the first Legacy title not based on an existing game IP. And naturally, the concept has been embraced by the wider game design community. Isaac Childres’ Gloomhaven features stickers that are added to the board when new territories are discovered, while Jamey Stegmaier’s upcoming Charterstone is a twist on a Legacy game in that once a campaign is completed, it remains playable as a variable worker-placement game.

Looking ahead, Daviau has teamed up with Ted Alpsach to give Ultimate Werewolf the Legacy treatment in 2018, while Pandemic Legacy Season 2 hits shelves later this year.

We caught up with Daviau to discuss the origins of the Legacy concept, what he makes of the state of creativity in the games space and how development of this year’s Pandemic Legacy Season 2 differed from the first time around.

How did you first break into game design?

It was 1998 and I literally answered a classified ad in a news paper. Remember that there was no BoardGameGeek, no YouTube, no content creators, and certainly not a place to get a degree in board game design. So your choices were Europe, role-playing games, old school war games, or the big toy and game companies. But I fell backwards into it by answering an advert. I had thought of doing RPG design and then this happened. To be fair, I was qualified for it, but it wasn’t a job one thought of doing in 1998.

Where did your Legacy concept originate from?

I’ve talked about this quite a bit in talks and interviews but the short version is that it was a combination of an offhand joke and a brainstorm. The joke was made about Cluedo, saying “I don’t know why we keep inviting these people to dinner; they just keep murdering people”. The brainstorm was looking at a way to challenge assumptions and I stated the assumption “The game doesn’t remember what happened the last time you played it” and, somewhere between the joke and the brainstorm, the idea was born.

Pandemic Legacy was a collaboration between yourself and Matt Leacock. Could you shed some light on how this process of design actually worked between you both?

We live on opposite coasts of the US so most of our collaboration takes place over video conferencing. I know a lot about what his office looks like and he knows a lot about mine. We meet anywhere from one to three days a week, depending on where we are in the schedule.

Matt is a very good note taker and organiser, so he tends to do most of that. I do all the writing, whether rules or cards or story. He does most of the work on the rest of the prototype. Ideas and concepts are pretty much 50/50. We find ourselves at conventions together one or two times a year, where we always meet and/or playtest. I’ve also been to his house a few times when I’ve found myself in the San Francisco area. It works surprisingly well. Between Skype and Google documents, I’ve got 95 per cent of what I need to collaborate.

Legacy has been deemed by many as one of the key innovations to hit board games in years. How do you assess the current state of creativity in game design?

The creativity is off the charts. I’m working every day to keep up. App enhanced games. Campaign games. Puzzle games. Mega civilizations. Micro games. Every few months there is something sort of breathtaking with the genre.

What advice would you give someone looking to embark on a career in game design? Does it help to hone your skills within a larger firm prior to attempting the freelance life?

It worked for me but, as I said, it was 1998 and that was how the world worked then. There is no shortcut to making lots of games and seeing how to get better at it. Eventually you’ll find your voice and you’ll also learn how to make better games faster. Whether that is with a company or just something done on nights and weekends doesn’t really matter.

Was the design process for Pandemic Legacy Season 2 smoother than your first time around with Season 1?

A bit. We already had a rhythm of how we built a play-test kit, how the campaign structure worked, where the pitfalls were, and what mistakes we could avoid. That said, we also had to do something completely new and there were a lot of mistakes that we found time to make.