Serial inventor Richard C. Levy talks about The Anatomy of a Toy and Game Inventor

Process, pitching and people: Richard Levy shares tips from The Toy & Game Inventor’s Handbook.

Richard, always a pleasure! We’re going to tie in on the subject of ‘The Anatomy of a Toy and Game Inventor’. I’m going to start with a quote from your book, The Toy and Game Inventor’s Handbook…

Thank you for having me back. And thanks muchly for the plug!

Not at all! In the book, either you or Ronald Weingartner wrote: “Toy and game inventors are people to whom elves still whisper. Their vividness of impression allows them to live in a never-never land where pumpkins turn into coaches and mice into horses, where cows jump over the moon and dishes run away with spoons…” I rather like that…

Thank you. We also wrote, product is king in the toy and game industry. That’s for sure! And inventors are as close to the throne as anyone can get. The inventor’s imagination is fired by compensation, of course, but I would like to think even more so by commendation, curiosity and challenge. If money is the key driver, people tend to come up short changed.

But even the most independent inventor can’t do it entirely alone, can they?

No. As you know all too well from your Mojo Nation interviews, independent inventors rarely work for just one toy or game manufacturer. Creators have their own ideas – and plenty of them – but mostly rely on manufactuers to take those ideas to market. In fact, the independent inventing community survives on its ability to generate a lot of different sparks for – as I tend to put it – new forms, fantasies, and fun.

I’ve noticed you use the word creator and inventor pretty much interchangeably…

Yes. I think the terms inventor, designer, developer and creator are all interchangeable. In a licensing agreement, they’re usually the signatory – as the licensor – and the manufacturer is the licensee. And as such, they often participate in advances, guarantees and a royalty stream.

That said, there’s no lack of creativity or inventiveness at the corporate level. Plenty of outstanding products originate in-house… And the contributions made by inventor relations people, research and development teams and marketing departments can’t be underestimated. Internal or external, the difference these people make to an idea is often the difference between success and failure. Bottom line, there are always one or more creative forces behind a product.

In that respect, are independent inventors still part of a team, do you think?

I’m not sure I’d put it that way, but the process takes teamwork, yes. It’s inconceivable that a company would have no impact on an outside submission. The path between idea, product development and eventual retail sales is a delicate and complex one… Many dozens of people might be involved. People the inventor never meets! Ron and I describe it as a serpentine chain… “A serpentine chain of egos, talents, events, whims, timing, technologies, designs, and marketing skills.” And if any link breaks, the entire effort could flag.

Because it’s fair to say, isn’t it, that if you had the mother of all ideas, but a publisher’s marketing department – just by way of example – couldn’t work out how to place it, that alone could scupper the deal?

Absolutely right. Everyone has to be able to see what they’re going to do with the product in order to do anything. So in the end, the whole is more powerful than any of the parts. And remember, it’s very rare for one person to have an idea, prototype it alone, pitch it, and walk away with 100% of a deal.

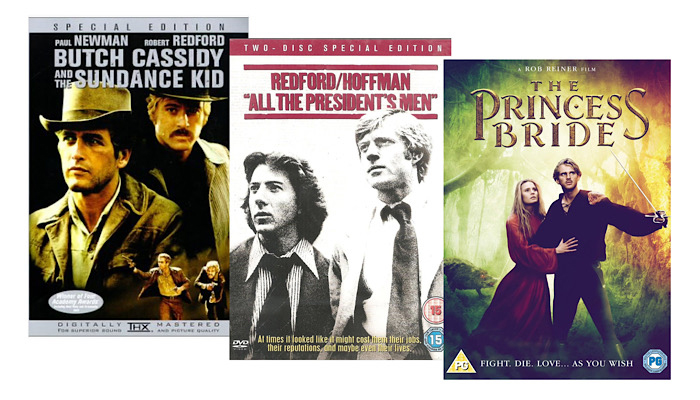

My first jobs were in the executive offices of the motion picture industry, Paramount International Films, and Avco Embassy Overseas Pictures. I’ll never forget a quote by the screenwriter William Goldman…

Oh! Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid?

Yes, and All the President’s Men, and The Princess Bride, among others. His quote applies to the toy and game industry, too. He said “Nobody knows anything… Not one person in the entire motion picture field knows for a certainty what’s going to work. Every time out, it’s a guess and – if you’re lucky – an educated one.”

Oh, I love that! Yes. ‘At this time, in this place, with the information I have, my best guess is that this idea would work for us.’ That’s what every yes means! Let me ask you this, Richard: what qualities unite all inventors, do you think?

That’s very difficult to say. A sense of fun, naturally – but then I think curiosity is a good part of it… I think it would have to be something like that because most people that create toys and games aren’t really qualified – in the literal sense of the word – to do it. By which I mean they’re not formally educated in design, say and they may not have golden hands.

No, toy and game invention is a much broader church!

Right! Among the inventors that Ron and I interviewed for The Toy and Game Inventor’s Handbook were people from a whole range of backgrounds… A barber, stockbrokers, newspaper editors and a registered nurse. We spoke to people that had been psychologists, social workers, real-estate developers and teachers… A TV producer, some advertising executives. And – you know, nobody ever believes this – but there was also a biologist, a priest and a nun.

Sounds like the start of a joke. “So a biologist, a priest and a nun walk into a bar…” Ha!

Good one! Ha! Beyond that, seasoned professionals often have less obvious qualities away from curiosity and imagination. Because the pros do tend to enhance their creativity with sharp business instincts. They better understand the process, they tend to better understand trends, and they often have a better overview of what’s worked and what’s failed in the past. That’s why – as I often say – toy and game inventing isn’t brain surgery… But it’s far from child’s play.

Lovely. Also, I know selling an idea is a completely different kettle of fish. There are charismatic extraverts that could sell fire to the devil… And there are more introverted inventors who sell their ideas seemingly just by making sure the right idea is in the right room with the right person at the right time.

You know, I sometimes think the best product creators can make people fall in love with an idea before the concept exists at all. It’s possible to pitch an idea from a drawing, for example, and fan that idea into a flame that illuminates! But a piece of advice I think is great is summed up by the inventor Jay Smith…

Go on…

Jay used to tell people to approach invention as a business. We touched on it a little just now… Beyond creativity, inventors must have other skills: marketing and sales, costing, and operations… Because, as Jay put it, “If you have one great idea and sell it, that’s luck… But if you’re going to do it over a long period of time, it has to be a business. If you have 1,000 ideas and you put 100 into sketch form and maybe 10 into prototype – you might still only sell one idea! But you do have to recognise those odds.”

Great advice. There’ll always be more ideas getting a no than ideas getting a yes. And in terms of getting feedback after a pitch, ‘resilience’ is, I think, a good word to use for new toy and game inventors… I always try to champion resilience – not persistence…

Out of interest, Deej, how do you see the difference?

To me, persistence connotes a certain stubbornness: “I showed 10 inventor relations people an idea… They all hated it. But I persisted.” That – ha! That I don’t like the sound of; that’s not necessarily a helpful quality! Certainly not as helpful, in my opinion, as resilience… Which would be me saying, “I showed 10 inventor relations people my idea… They all hated it, but based on their suggestions, I made tweaks. I made changes… I acted on the criticism, but I was resilient. Does that make sense?

It does! In my case, unless someone points out a fatal flaw in my concept, I do tend to stay the course. To me rejection is just a rehearsal before the big event. I refer to rejection as a Pasadena – just to keep it light, and not too serious! My motto: never give up, never grow up.

Ha! And I know I know you live by that.

And if you’d like to share it, David Berko gave some wonderful advice about listening to feedback. It’s a Do and Don’t list – you can print that here if you like!

Well, that would be wonderful! David Berko – for those that don’t know – is a former Hasbro inventor relations executive and I.D.I.O.T. Award winner. We’ve done an interview with him that people can read here. So yes! Let’s end on that Richard, that would be perfect.

David Berko’s Do and Don’t Pitching Advice

Do make sure your presentation is at a point that it can sell itself. Once you have presented a product, it has to survive on its own in the corporate organisation.

Do your homework. There is nothing worse than seeing an item that has been in the company’s line for 10 years.

Do bring back good ideas that have been rejected if you think something has changed in the marketplace. But give it time – and not just a week or two.

Do follow up, but don’t call every day. Give it a few weeks.

Do listen to feedback and try to respond. The company gives this information to help you as well as itself.

Don’t work on products based on a trend or fad that is at its peak. You can be sure companies have been aware of these products for some time. Companies notice that there are products based on this trend on every street corner.

Don’t work on items from another company and expect a company to be interested. Hasbro would not be interested in Barbie accessories, and Mattel would not be interested in a new idea for Mr. Potato Head.

Don’t assume that the executive you are presenting to can read your mind. Explain concisely what your idea is without omitting anything important.

Don’t try to sell something that has already been rejected by that company. Once a company says no, don’t try to talk them into changing their minds; they’ll only send it back again, which is a waste of your time as well as theirs.

Don’t lie. Berko once rejected a product based on safety reasons. The inventor didn’t know that a particular component in the product was potentially unsafe. Once Berko informed him, the inventor said that he would put the item on the shelf and not try to sell it. Sometime later, when Berko moved to another company, he saw the same item in the inventor closet, from the same inventor who was still trying to sell it.

Don’t oversell. The company has only seconds to get the idea across to the consumer. If you need a 30-minute intro to get your point across, the company probably won’t be able to sell it, either.

–

To stay in the loop with the latest news, interviews and features from the world of toy and game design, sign up to our weekly newsletter here