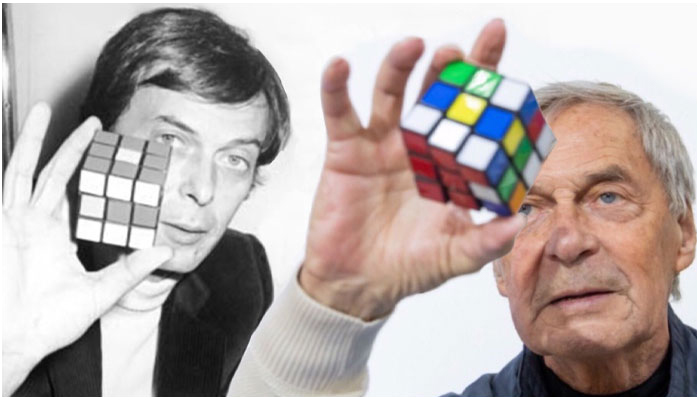

The Rubik’s Cube at 50: Ernö Rubik tells Pete Jenkinson how the iconic puzzle came to be

Ernö, I know how busy you are so thanks for joining us. I guess the thing most Mojo readers would want to know is how the heck you came up with the cube in the first place?!

My experience is that if you are looking around all the time, you will find something that is inspiring. Maybe you see some irregular elements in the environment you’re in, for example. But one of the areas of life I’m interested in is geometry. Geometry is part of math and it’s part of science, but it’s a very pure one; it’s very clear and innocent. And the richest part of geometry is the three dimensional one – trying to understand space relations.

So you’re constantly looking around, constantly finding inspiration… And you were deeply interested in spacial relations…

Another of my standing points is that I love to work with materials. I like the workshop, I like the tools; I like using my hands to create something I’m able to touch and turn and correct and everything. These things might look like they’re in contradiction, but they’re very close to each other and I was interested about this knowledge and what is connected with what.

Looking to join dots!

When I was younger, I studied art, especially in sculpturing, which was a three-dimensional art activity. But then I turned myself in the direction of architecture – which, in my view, is very close to sculpturing. But it has some kind of technical and practical elements. Because if you think about it, we use the result of architecture: we are living in it, we are working in it, we are viewing it and so on. So we are making an environment for us – humanizing the environment, as some say. Which on the one hand is good, one hand is bad… A contradiction.

But then, what human beings do is full of contradictions. Another route that was guiding me was just thinking… Abstract thinking, to imagine something and try to understand it. For example, chess is a very good practice for that. I loved solving chess-problems…

You mean when you’re presented with a specific chess scenario to solve? Rather than playing a full game?

Yes… It’s much more popular to play chess with an opponent. But a chess magazine might print chess problems that show some pieces in play – and there is a target. They might say, “Black wins in two steps” for example. I loved to do that when I was a teenager. So they were my interests; the different directions of the surroundings and my existence as I was growing up. And it ended when I finished my architectural study and got my diploma… I’m a diploma architect – with not so many buildings because of the queue!

Ha!

I also went to an art school which was working in an applied-art type-of-thing at a time when – in Hungary especially – it wasn’t common to speak about design and so on. Today, we know it’s an important part of human activity; the technical part and the artistic part crossing each other… Forming the environment with objects. And in my view, architecture is very similar – the scale is different, but the specialty of architecture is that you go into the result of your work… Unlike a painter, say, who can only see their work from outside. Anyway, when I finished this study, the director of the school asked me to stay. I don’t know why – but I thought, ‘Why not?’

How old would you have been at that time, Ernö?

I was about 27. And that was a very interesting time – I was really excited and thinking about teaching because I hadn’t liked my schools very much. And I tried to think why that was and what would make a difference. In the meantime, I was finding and facing challenges and working on it. So it was a busy time. But know, your 20s are the best time in life because you became somebody. I’m not speaking about prestige; I’m speaking about character and who you are… You find your capabilities; you find what you like.

You get a greater sense of self…

Anyway, I started lecturing form studies, discussing art without function; looking at construction space; using space without a special type of function… And getting students to think about simple materials: paper, wood and so on. So that’s between art and engineering – very difficult to define, but very close to my original interest in geometry. And I got the idea to try to demonstrate for the kids and for myself the potential of this kind of thing. And what I found interesting was what could I do with one of the simplest forms, what is known in the field as a three-dimensional form, which is part of the platonic solids. As a result of that, the Cube was born in 1974 – 50 years ago.

And when you say “born”?

Well, not at once! A human being is not born at once – it’s a process. And the Cube was a process… The idea, what to do, thinking on it, working with material, making models and looking for the potentials of the order of space. In one sense, the idea that it was engineering and sculpturing or art crossed my mind. But I wasn’t working on a toy and I wasn’t working on sculpturing… I was working on something that I found interesting and very rich in content and potential, using all of the things which are close to me: colours, forms, conception, dynamic movements and the technical parts of it.

You didn’t start with the three-by-three Cube, though?

No, I started more simply – two-by-two. Because one-by-one, you can’t do anything with…

Ha! No, that would be a dice!

Yes! It’s beautiful, and you can try your luck with it, but that is not enough! But I found a solution for the two-by-two cube, discovering that it’s a very dynamic thing – the elements are moving and changing… But to recognise this, you need some kind of sign. I am a simple person, so I wanted it to be clear and easy to recognise. I simply used colour as a signing method because that is very easy to understand. If you are using letters, there are different languages, and they are much more informed…

So the Cube as we know it is taking shape… But it’s still not a toy or a puzzle in your mind at this point. When did you start thinking it could be more than a tool? That it could be a product?

Well, after I made the construction and was discovering the potential of the object, I was sure it was a very interesting thing… And if I found something interesting, I wondered if it could it be interesting to somebody else as well. So why not create a product from it? But that was not an easy task, especially at that time. In general, that would not be an easy task! But especially at that time and in Hungary, which was part of the Soviet Bloc.

And at some point, you chose to make it a three-by-three cube. Why was that the right size?

If you have a task or are thinking about creating something as a designer, you are running for perfection – or as good as possible, and working well at least. That was very important to me, and I think that’s a natural target for every designer: to make something new, make it useful, make it good to handle, make it beautiful and so on. This is why details become important. So even after it was a three-by-three, I still had to decide on the exact size. The last step I took, for example, was to reduce it by three times one millimetre – one millimetre in every direction – because it then became very natural to the size of my hand.

Then, once that was the size of it, for three years the production started, and the sales started in Hungary. That was a closed economy, but many cubes were sold and I felt the potential of the product and tried to distribute it much wider. Even when we finally found an American company that was ready to handle it, it was not an easy task because traditionally a puzzle was not very important in the toy field. It had no volume really; a puzzle was something small and cheap. You buy it, you try to do it, it’s tricky… But after that, what does it do?!

But they took the risk!

Yes – and, at first, we continued to manufacture it in Hungary. But the contract said that if they weren’t capable of fulfilling the volume, we got the right to manufacture it elsewhere. Well, as you know, during the first three years it was a real wonder because it practically at once generated a craze. And in those first three years they sold out 100 million pieces.

100 million pieces! Astonishing! And I know we’re running out of time, Ernö, but one other thing I wanted to ask about is why you prefer to say you discovered the Cube rather than invented it?

This is very interesting to me because I’ve seen some debate as to whether a math formula is an invention or a discovery. For me, I don’t like the word ‘invention’ because it is much more about discovering and using potential. So my view is that the Cube was discovered rather than created from nothing. Because we can’t create something from nothing, can we? So it is always there, just hidden until somebody is able to see and discover it.

Fascinating. Well, Ernö, you’ve given us such extraordinary insights – thank you. I’ll just say that if anyone wants to know more about your journey, they can read about it in your your book: Cubed: The Puzzle of Us All. Also, I know people can read more about Tom Kremer’s involvement in the interview Deej Johnson did with Mike Moody, which people can read here.

–

To stay in the loop with the latest news, interviews and features from the world of toy and game design, sign up to our weekly newsletter here