The secrets of creativity: what do magicians know? Prolific inventor Mark Setteducati tells all…

Mark, thank you so much for joining us. Let’s start with the obvious question… How did you get interested in magic? And how did that lead to toys and games?

My interest in magic began when I was around 10 years old. I saw an ad in Boys Life magazine from the Top Hat Magic Company in Evanston Illinois. I sent them ten cents to get their magic catalogue, then ordered tricks from it.

As a kid, I was also interested in art, which – after high school – led me to attend The School of Visual Arts in New York where I graduated with a BFA. While a student at SVA, I’d look for freelance design work… One job I took was with an entrepreneur who was looking for artists to create designs and content for hexaflexagons…

Hexaflexagons! Good Lord… Perhaps I should interject and say that a hexaflexagon is a mathematical object, often made of paper… It’s folded and constructed so that you can conceal or reveal different faces.

Right, right… And that really fascinated me. But the thing about the job was that the payment was to be a royalty. I didn’t know you could collect royalties for doing a job, and to me this sounded great!

Why was that?

I figured I’d finish a project and sit by the mailbox collecting checks, possibly for the rest of my life! So I became fascinated with the hexaflexagon, and created several ideas for it, including making it into a puzzle and a game. I became friends with the entrepreneur, and in addition to working on the hexaflexagons, we created a board game together that we started to pitch to game companies. Well, one of the companies we presented it to was MEGO, who almost licensed it.

Just to clarify, Mark, when was this? Roughly?

Well, we started attending the New York toy show… My first one being in 1975. The entrepreneur was mainly interested in starting and running a company, and I was only interested in coming up with ideas and licensing them. I remained friends with him while he focused on his company, and I continued to pursue the toy business. I made contacts through MEGO and the toy shows, creating new ideas and trying to license them, which I have managed to do since then.

Fantastic. And I’m itching to ask you this… To what degree, do you think, does your being a magician help your creativity?

It helps it a lot! There’s an old saying associated with magic, “The hand is quicker than the eye.” Most people think that magic relies on being quick, but this isn’t true. In fact, the eye is much quicker than the hand. Magic relies on the idea, design, and performance of the trick. Magic is a well thought out plan that starts with an idea and uses and combines many tools to achieve the illusion.

“Magic is a well thought out plan that starts with an idea and uses and combines many tools to achieve the illusion.” That’s as good a summary as I’ve ever heard! And so that that’s easier to digest, Mark, what are ‘the tools’?

Well, some of the tools we use are physical and some are performance – which are both equally important. Examples of physical tools are things like the props, playing cards, coins, objects, threads, magnets, scientific, mathematical, and mechanical principles…

Examples of performance principles are misdirection, timing, psychology, the exact story and words we say when performing a trick. These all guide a spectator’s mind off what we’re secretly doing… Sometimes even changing a trick in the middle of performance, either to make an effect stronger or covering a mishap.

Right. And connecting the dots, how does that relate to invention?

Inventors mostly use and think about physical tools, such as the prototype, function, and design of the product. They’ll take into consideration the use and play value of the product, and create a name, storyline, and theme… But the physical tools are by far the main inventors’ tools. So because magicians have this whole other toolbox of performance that inventors don’t have, it opens a whole other universe of aspects magicians think about, apply, and use in their creative work, and in their everyday life.

Brilliant. I agree completely… Completely! I’ve been planning to ask several magicians about this but you’ve covered it so well I’m not sure it’s necessary! Thank you. Let me get a bit further into the creative weeds… In my experience, you’re one of the few inventors that habitually uses the words priming and incubation… For the uninitiated, why are they important?

A person’s individual background, reality and experience primes their subconscious – even when they’re not consciously working on the idea… A good idea can then take time – sometimes years – to incubate before an “Aha!” moment!

So even when you suddenly come up with an idea, you’re not really suddenly coming up with an idea?!

Right. It seems like you just come up with an idea, but really your subconscious mind was incubating it and secretly working on it all along. Your subconscious is always working; cooking up many ideas that someday get revealed to you.

You also speak about invention and styling, or layering… How would you describe the difference and relationship between them?

Let’s say you have a magic trick: a card trick, stage illusion; any trick… There’s a mechanical or technical way the trick is done; the principle. This is the invention. Then you have the script and theme – how you dress and present the trick. This is the styling. It’s the same for a toy, game, or puzzle…

In what way?

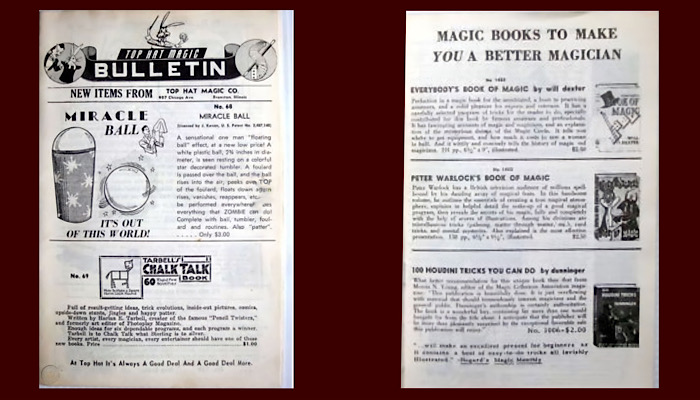

You have the product idea, which is the invention; then you have to dress and style it. You have to create exactly what it looks like and exactly how to present it, sometimes including a story. So when I created the Mr. Creepy Magic Set, for example, I didn’t invent any new tricks… I took classic magic tricks and styled them with a creepy theme. I took the old Ball and Vase trick, for instance, and made the vase a monster’s head, and the ball into a brain!

And – In your opinion – is almost is that easy to do? Or hard?

Hard! In fact, great styling is as hard as – if not harder than – inventing something new. Usually, some people are good at inventing and others are good at styling. An example of great styling was the G.I. Joe toy helicopter, which was designed by my late friend Bob Carignan. When G.I. Joe was introduced in the 1960s, it was a 12-inch-high soldier doll. The toy company wanted to make a helicopter for G.I. Joe, and – obviously – wanted the doll to sit inside it…

Right…

The problem was that if you proportionately shrank a real helicopter, so that a 12-inch doll could fit inside, the toy would be enormous; way too big for a toy. Bob had to take huge poetic license and style the helicopter to be much smaller without it looking strange or weird, while keeping the integrity and look of a helicopter. Bob also included some invention in his design – a finger trigger that allowed the propeller to spin. All of this was a very difficult problem, and if you google 1960’s G.I. Joe Helicopter, you can see how Bob pulled it off. It seems completely natural, maybe even obvious, which is exactly what great styling should do.

We’ll stick in a photo of that… And this layering might also include a storyline? How important is that?

You should try to take your ideas as far as possible so that everything is resolved, and the concept feels completely natural and flawless. A storyline is part of tying everything together so it all makes sense. And yes, the story can also add another layer to give your concept more depth. Also, a story can be present without words…

Do you have an example of that?

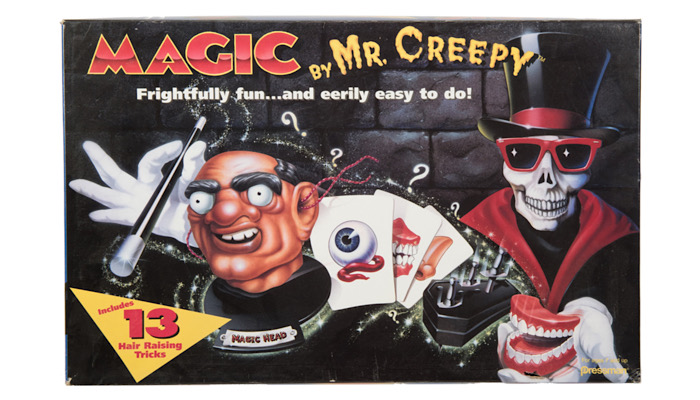

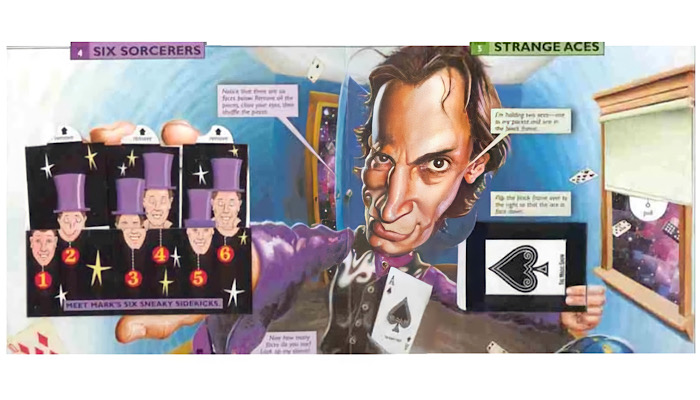

Well… Most people that have my Magic Show book probably never realise it has a story, for example. Normally, books are illustrated in one style of artwork, but each page of The Magic Show book is illustrated in a different art style… In itself, the change in art style is obvious to the reader; the reason for it, however, is not. The book starts with realistic artwork then, as the pages progress, the art gets more strange and surrealistic.

I have a copy right in front of me… I can see exactly what you’re saying. And what was the reason for this?

The reason for this is that you start the book in the real world, then as you progress and start getting fooled by the tricks, the art gets more surrealistic, bringing you into a strange world of magic… Towards the end of the book, the art returns to the realistic style, bringing you back from the surrealistic and magical world you just visited. Even though most people don’t consciously realise this, I believe they subconsciously get it. It adds another layer to the concept that makes the whole experience more powerful.

Got it. Let me ask you this, Mark: How do you choose which projects to develop?

I work on many ideas and projects at the same time, and have an inventory of projects I’ve worked on over the years. Because I work for myself and don’t have a ‘job’, I don’t get hired or get assignments to work on stuff – so I have to generate my own projects and try to make a living! I have to pitch ideas to companies or find a way to get them out there. For those reasons, my choice of what to work on is very practical…

And how do you go about that?

I look for opportunities first, then either come up with a new idea or draw a suitable one from my inventory. Opportunities arise in different ways: attending conventions or trade shows; meeting new companies or entrepreneurs; speaking or participating at conferences, or just meeting with other inventors and agreeing to collaborate.

One example of your creativity that really intrigues me is that, every year, you make – by hand – highly-innovative Christmas cards. Can you tell us a little about that? Is it just for fun, or is it a valuable exercise?

I’ve learned a lot over the years from doing the cards! They’re a huge effort, but they’ve probably taught me more about the creative process, design, and inventing than anything else could ever have. The recipients think I do the cards for them, but the truth is I do it for me!

That’s a much more emphatic answer than I expected! How did they start?

A close friend and mentor of mine, Peter Jacobsen, was an artist. He made an original Christmas card every year… In 1976, he sent me a card, and I made him one in return. Every year since, for over forty years, I’ve been making and sending these cards.

Why are they so important?

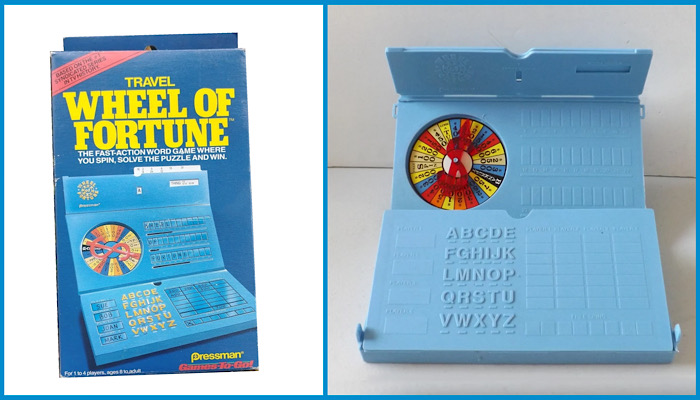

Designing a Christmas card forces me to come up with a different solution to the same problem. Now, after many years, the cards serve as a diary of my creative process over time. For example, many of the ideas turned out to be research for what became projects such as my Travel Wheel Of Fortune game, and my self-performing illusion book, The Magic Show…

When I first started doing them, I didn’t know how valuable it would be; I didn’t know the cards were useful until years after the fact. Only looking back did I see the connections. And because I send the cards to my close friends, I can’t show it to them because I want it to be a surprise when they receive it!

Got it. You’re forced to create…

Right: I’m forced to create the idea without showing it to people for input or feedback. I’m flying totally solo, and I make every one by hand, which is also very important. If I just came up with the idea and gave it to somebody to make, it wouldn’t be the same commitment necessary to come up with a great idea.

And it’s just one idea a year?

Well… I always make the cards in batches, including printing them, which I do by going to a copy centre and photocopying them. This is because, as I’m assembling them, I sometimes notice things and make running changes, or I test a different colour or something. I usually make several trips to the copy centre as I go along, printing a small batch each time. It would be a lot easier – and much cheaper – to decide on a final design ahead of time and print them all at once, but that would interfere with my creative process.

It sounds hugely time consuming!

It is, because I make over 100 cards: it takes me the whole week before Christmas! It’s so much work; it forces me to be really happy with the idea. There were several years, after I’d printed and was assembling cards, that I realised I wasn’t happy with the idea for all the effort I was investing. This pushed me to think further, forcing me to come up with a much better idea than I would have done without the commitment of hand making every card myself.

Am I right in saying, Mark, that you have the world’s largest collection of novelty pens? Do they serve a purpose?

Yes, but I don’t think of the pens as my pen collection; I think of them as a collection of IDEAS; a metaphor of creativity. In the 1980s, I was teaching a creativity and design class at New York’s School Of Visual Arts and came across a few novelty pens in a gift shop. Each pen had a different and unique idea…

I realised this would be a great visual way to show my class how you can take an ordinary object and design it in different ways; the same problem – design a pen – solved many different ways. I continued to look for and buy novelty pens, and I now have thousands! It’s surprising how many different solutions there are for the exact same problem.

That’s what a pen is? A solution to a problem…

Of course. There are two kinds of solutions to a problem. The first are ideas that you could have thought of had you been given the same problem. The second are ideas you never would have thought of… Even if you’d worked on the problem for many years, that idea would have never come to you! These are the ‘Aha!’ ideas. They’re the most valuable because they open up new doors in your mind and get stored in your subconscious for later use.

Why collect them though, Mark? Why not just see them, acknowledge them, and say: “that’s great!“?

I find that when you collect different ideas, when you surround yourself with them, you somehow absorb them subconsciously. I think it’s important to actually commit yourself to collecting; to actually buying something. If I’d seen all those pens but hadn’t bought them, they wouldn’t have been part of me as deeply as they have.

Great answer. And just to satisfy my curiosity… How many pens are we talking about?

Thousands! And even though I own thousands of pens, every time I see a new pen idea that I don’t have, or have never seen, I know it. Then, all of those ‘Aha!’ pen ideas, all of those different approaches to solving a problem that I’d have never dreamed of, have given me a roadmap or lesson on how I might approach and solve a future project. So when I started collecting the pens, my purpose was to teach others about creativity. I only realised later that I was actually teaching myself about creativity!

I’m going to come onto your I.D.I.O.T. award in just a moment. For now though – finally – what piece of advice do you feel all new game inventors should hear?

Do not be motivated by money. Work on things and pursue all that intrigues or interest you, even if you don’t see a way you might make money from it. For example, in 1993 I co-founded, with Tom Rodgers, The Gathering for Gardner – a conference celebrating the life and work of mathematician and magician Martin Gardner…

Not only was I never paid anything for all my work over the years, I had to pay all my own expenses – it cost me money! Over the years I invited several friends along, but even though they were highly interested and would’ve been a great fit and got something out of it, they couldn’t see how they might profit from it. And actually, it never occurred to me that someday I would profit from my involvement!

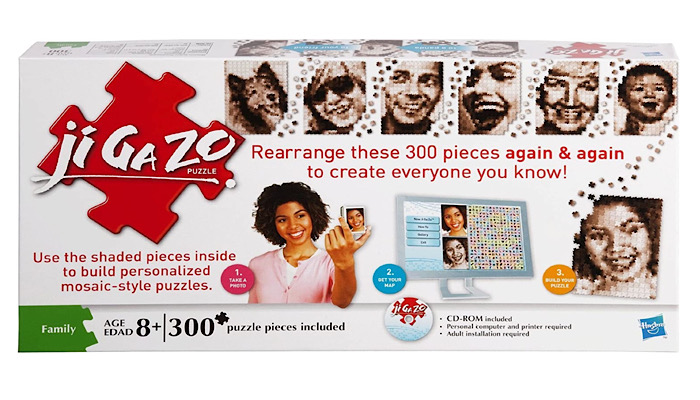

Nevertheless, it was at the first Gathering that I met Ken Knowlton… Many years later, we collaborated to create one of my most successful products, the Jigazo puzzle. Had I not been involved with the Gathering, Jigazo would have never existed. On the other hand, there were many interests that I pursued that never amounted to anything; but one could say those things and experiences became part of the mix and collection of who I am, and probably get expressed in what I do, even though I may not be able to connect those dots to a monetary or practical gain.

Wonderful. So, Mark… You’ve picked up a lot of awards during your long career. In 2002, though, you were awarded the prestigious I.D.I.O.T. Award. This is arguably the most coveted of all! What did it mean to you?

Every year I would go to the London Toy Fair before the Nuremburg Toy Fair. The UK toy show was always the highlight of the trip because of the Inventors Dinner. In fact, I know several international inventors who would go to the UK Toy show only because of the dinner. In those days, I attended every dinner except for the first one without missing any. When I received the award, it was very special because all the people that attended were either my friends or people that I had great respect for. After receiving the award, each following dinner you attended you would bring your award medal and wear it at the event. It made you feel like you were a member of a very special club, which I guess I am.

No question you are! And dare I ask, Mark… Why do you think you got it?

Why do I think I got the award? Probably because they couldn’t think of anybody else to give it to!

Oh, gosh! Too modest; too modest. I’ll leave it there, though, Mark. Thank you so much for making time

–

To stay in the loop with the latest news, interviews and features from the world of toy and game design, sign up to our weekly newsletter here