The Seven Myths of Toy Sustainability: Activist Sharon Keilthy’s surprising views

Sharon, you recently gave a talk about toy sustainability to attendees of the world’s biggest toy fair, Spielwarenmesse in Nuremberg. I thought you ended it with an important point about judgement… How did you sum it up?

I did! I find when I talk about how unsustainable toys are right now, and how to fix that, people often think about the toys they’ve made – and indeed their own children’s playrooms – and feel guilty! But when plastic was first used in toys, no one knew about climate change, or petro-plastic’s role in driving it. It’s not our fault that the industry is as it is now. So let’s skip the guilt and focus on the future! I believe our children will judge us on just one question: “What did you do, once you knew?”

Alright. And in regard to the word that you use to introduce yourself – ‘activist’… Let’s disabuse people of the idea you’re going to glue yourself to their toy fair stand! In what way are you an activist?

Ha! No, it hasn’t come to that yet. Although if glueing myself to something would take toys from “World’s most petro-plastic-intensive industry” to “the children’s industry leading the world on protecting their planet”, I would! But for now, my activism is running the world’s first eco toy store, Jiminy Eco Toys in Ireland. It’s a social enterprise that exists to inspire a playfully sustainable world – by making it easy for people to choose a gift that delights both child and planet – and by influencing the global toy industry.

So Jiminy Eco Toys – www.jiminy.ie… How did that come about?

It was 2018, and my daughter’s fourth birthday was coming up. I went to a nice toy store in Ireland to get her a gift. By then I was awake to the plastic problem; the carbon emissions, the trash crisis… So I wanted to get her something she’d enjoy, but that I could also feel good about – something plastic-free and made locally.

You’re in Ireland, so ‘locally’ would be defined as…

I’d define ‘locally’ as ‘in Europe’. Even Eastern Europe is only 2,000km by road from here, whereas China, where 80% of toys are made, is 22,000km by sea. Anyway, I came out of the toy store empty-handed. There was nothing plastic-free and locally-made in there. And I thought: “How can we expect people to choose sustainable options when they aren’t on the toy store shelf? And if not me now, then who, when, to change this?”

And that led you to start Jiminy Eco Toys?

Exactly… I started the toy retailer I wished the others were! A toy shop that offers all the popular types of toys, for every age from babies through teenagers – just the ‘eco version’. In other words, strictly no virgin petro-plastic, and made in Europe to minimise toy-miles.

How did you start? Not with a website, presumably?

No, I started in my local park market on a cold, dark Saturday morning in November 2018. It was a folding table, about 20 products, and me – terrified and not knowing what I was doing. Four years later, Jiminy.ie is an online store and one of the largest independent toy retailers in Ireland.

So Jiminy’s now been going for four and a half years. Environmentally speaking, what difference has it made?

Well, we’ve empowered over 15,000 people to choose gifts they could feel great about. We’ve sold over two-million euro of sustainable toys. If we assume that replaced the same value of unsustainable toys, the climate impact is like having saved 4,500 mature trees from deforestation.

We’ve also brought awareness of why and how to choose a sustainable toy to a mainstream audience: through our customers and online community, a Christmas pop-up in Ireland’s largest department store Arnotts, and features in all the Irish press including The Irish Times and Ireland’s most-watched TV show: The Late Late Toy Show.

I’ve also been sharing what I’ve learned with the global toy industry including co-founding a sustainability learning community at Women in Toys, lecturing on sustainability to toy design undergraduate students, sitting on the Toy Association Sustainability Committee, and co-organising a “sustainable plastics for toys” conference this March.

That’s bio!TOY, presumably; we’ll make sure we cover that in a news release as well. Okay, that’s fantastic! So let’s dig into some nitty gritty… The bulk of your Spielwarenmesse speech focused on building a case for change in toys. Tell me about it! Where’s the beef?

The beef, as you put it, is that – as things stand – the toy industry is linear, and intensely polluting and wasteful at the start, middle, and end of a toy’s life.

How so?

At the start of a toy’s life, making and transporting them emits so much carbon dioxide, we’d have to plant a billion trees to absorb it. Mainly because toys is the world’s most petro-plastic-intensive industry, with 90% of them made from it.

So the carbon footprint is mainly the plastic? Not the shipping?

Correct! Making plastic from petroleum is so polluting, that shipping the finished toy 22,000km by sea from China contributes just 10% of its carbon footprint – the other 90% is the plastic.

Yikes. You’ve also said something I thought was very interesting about what you call a toy’s midlife. First of all, what do you mean by that?

A toy’s midlife is when it’s used as a toy! The waste here is how little time, on average, a toy actually gets used for. In Ireland, which is comparable to most of the developed world, the average child under 12 years old receives €450 of new toys every year…

For our readers outside Europe, four hundred and fifty euros is roughly what? Five hundred and fifty dollars?

About that, yes…

And by the time people read this, I’m guessing the value of the British pound will have plummeted again… Let’s say it equates to three or four thousand…

Ha! Well, hopefully not. €450 is around £400.

Well, we’ll see! So the average child gets given a whole heap of toys every year…

Right. Some studies show new toys get put to one side within a month. For a product to reach its end-of-life stage so quickly is a huge problem because they’re hard to get rid of responsibly…

Don’t people simply give them to friends, Sharon? Or charity shops? Or hold onto them as hand-me-downs, even, for their next child?

Many do and that’s great. But used toys are funny. It’s often socially-unacceptable to give a used toy as a birthday or Christmas gift. Charity shops often decline toy donations, especially soft toys, because they take up space and don’t sell quickly. And many toys are mixed-material making them very difficult to recycle.

Interesting. So let’s recap: there are three areas to address: the toy’s start of life – the production and shipping; its midlife – how to make sure it gets well used; and its end of life – what happens when it’s broken or worn out and one needs to actually dispose of it. Have I got it?

You’ve got it!

Perfect! Now when I first spoke to you about this, Sharon, you mentioned people are often confused about sustainable toys… What ARE the seven common misconceptions you’ve noticed about sustainable toys?

One of the big ones is that a sustainable toy has to be made of wood. In my store, though, only 28% of our eco toys are wood – and that’s sustainable wood, by the way. The rest are bioplastic, recycled plastic, recycled cardboard, recycled paper, recycled wood, organic cotton and beeswax.

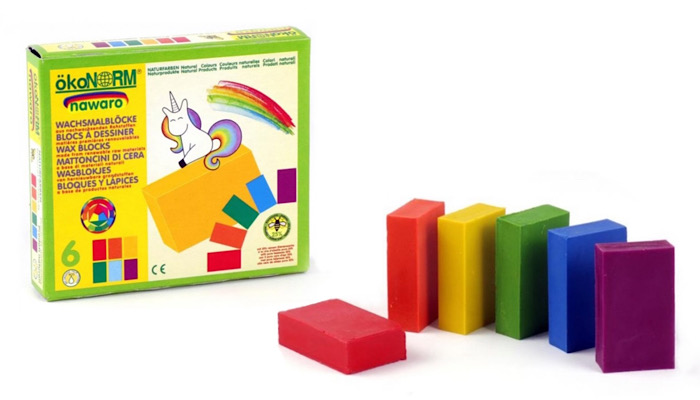

Beeswax?! What would be made out of beeswax?

Crayons! Most colouring crayons use paraffin wax – a product of petroleum. Some companies also produce beeswax modelling clay. In any case, there are lots of materials available beyond just wood. Materials like bio-plastic or wood that are made from plants are renewable, and plants release oxygen and absorb carbon dioxide as they grow. And recycled materials tackle two crises at the same time: they have a low carbon footprint – and they also use-up waste, and put a value on waste, helping with the trash crisis!

Perfect. I noticed you use the word recycled much more than you use the word recyclable. Is that an important difference? Should we be drilling into that?

Yes! People often conflate the two. ‘Recycled’ means “made from waste – low carbon footprint and helping with the trash crisis.” ‘Recyclable’ means “made from virgin materials contributing to climate change, not helping with the trash crisis, but can in theory be recycled in 25 years when you’re finished with it, if put into the right recycling stream”.

I might shorten that in the graphic…

As you might infer from what I say, it’s another misconception about toys to say that it’s important for a toy to be recyclable.

I think that would be a surprise to a lot of people!

Yes! If a toy’s durable, it should be passed from child to child, and we can reasonably expect it to be used for 20 or 25 years – maybe more. I can see you’ve got some old LEGO behind you, for example… You’ve probably held onto some of your LEGO for some time, right?

I’m told I’ve held onto all of my LEGO for far too long!

Right. So if kids are getting quality toys now, toys that last, that are made from already-recycled materials, that’s more important, I think. The recycling technology and systems will be entirely different in twenty years anyway.

And misconception three would be that it’s important that a toy be biodegradable…

Right! Why would we want toys to biodegrade? What if your toy gets left in the bathtub? Or in the garden, or even just on the windowsill – would you want it to start to decompose? That would shorten its useful life and create child safety hazards. And in any case – generally speaking – recycling is usually better than biodegrading.

Recycling is usually better than biodegrading because…

Take that sheet of paper you’re writing on… Think of the energy and resources to biodegrade it into soil, grow a new tree, chop it down and process it into a new sheet of paper! It takes far less to recycle it into a new sheet of paper…

So you’re saying when we GET the toy it should – ideally – be a high quality one; a durable one – made from recycled or bio-based materials… When we HAVE the toy we need to keep it as long as possible… And, in an ideal world, when we get RID of the toy, would we also recycle it?

Exactly, yes…

Alright, I can see we already explored a misconception when we discussed transport… You made it clear that creating toys in virgin petro-plastic has a much bigger carbon footprint than transporting toys from China. Just to tie that one off, why, then, does Jiminy focus on toys made in Europe?

Ah! Yes… Because we’re perfectionists! While we’re saving 90% of the carbon footprint by avoiding the virgin petro-plastic, that isn’t enough for us. We want the whole 100%!

Your next common misconception is one that I think consumers hold; possibly retailers too… And I wonder if manufacturers might perpetuate it – inadvertently or otherwise. I mean the misconception that, as you describe it – sustainable toys are “all beige”. What do you mean by that?

People associate “sustainable” with “Scandinavian chic”. If it’s all neutral tones, it must be sustainable. But there are completely unsustainable toys in neutral tones, and highly sustainable toys in rainbow colours! And importantly, mainstream toy stores are all garish rainbow colours because that’s what the majority of kids want… So if we’re going to create ‘eco’ as the new normal in toys, “eco toys” need to match that. But I’m curious, in what way do you think manufacturers might perpetuate this misconception?

Well… In the same way that manufacturers often continue to perpetuate the idea – rightly or wrongly – that there are toys for girls and toys for boys, I wonder if they have a reason to perpetuate the idea that eco-toys look and feel a certain way. And that, in turn, might lead to the misconception that they’re expensive.

Right, because they’re not necessarily! Our eco toy store has something for all budgets, and compares quite favourably on price to unsustainable mainstream toys. We only struggle to find sustainable alternatives to the very low-price ‘throwaway’ types of toys.

And the final misconception, Sharon, might be one of the biggest… The idea that sustainability is all about the packaging…

Absolutely. If you were to take a toy and weigh it, what percentage of the overall weight, do you think, would the packaging comprise? 2%? 5%?

I wouldn’t even like to guess. But, granted, it would be a comparatively small amount…

Exactly! And proportionately, that’s also likely to be its share of the toy’s environmental impact. So why have so many people in the toy industry been talking about sustainable packaging for 10 years or more? But not been talking as much about the actual toy’s climate or trash footprints?

Well, that might of been a rhetorical question, but I suppose the answer would be because packaging is easier… And not to be contentious, because I’m enjoying the conversation, but – arguably, it does make sense to start with the packaging… It’s a faster, easier fix. Companies could start sorting that out long before they worked out how to do the slower, harder things.

Yes, absolutely – and it’s right to start with the quick wins. I think another influence on this has been that to date, there’s more legislation affecting packaging, stemming from regulation of food packaging waste.

Food being a bigger industry? And a more disposable one?

Right. Anyway, if we’re working on the sustainability of a toy’s packaging, we need to consider its climate and trash footprints.

Fantastic, Sharon thank you so much for making time to join us and debunk those Seven Myths of Sustainability. I know you also have thoughts on how to maximise the use a toy gets – things like design for repair, toy rentals, and mainstream pre-loved retailing. Perhaps I can invite you to come back and discuss that soon?

Sounds good!

–

To stay in the loop with the latest news, interviews and features from the world of toy and game design, sign up to our weekly newsletter here