University Games President Bob Moog on passionate inventors, cautious buyers and the importance of integrity

Bob Moog – President at University Games – discusses the three things that all great inventor pitches have.

Bob, it’s always great to chat to you. Let’s start at the beginning! Some people we speak to wanted to get into games from an early age; others sort of ‘fell’ into it. Which side of the fence are you on?

Well, here’s the thing. At the time, I thought I was on the latter side. I knew I wanted to run my own business, but I wasn’t particularly picky about what I did.

Before starting the company in 1985, we looked at three different types of businesses. We looked at starting our own microbrewery because the laws in the US had changed. It was the first time since prohibition that they had allowed people to brew on premise and then sell it. It was considered bootlegging up until the Eighties! We decided not to do that because it would’ve taken too much capital investment.

With beer out the window, what was business idea two?

The second thing we considered was a novelty ice cream company. At the time, most ice cream was just ice cream on a stick with chocolate on top of it. Even things like Magnum, which you have in the UK, didn’t exist. The Dove Bar had just come out so I thought that would be fun to do… But we would’ve needed refrigerated trucks to keep the ice cream cold and the life cycle of food isn’t that long, so I got nervous that we’d end up with a warehouse full of melting ice cream.

Ha! So with ice cream off the table, enter games…

Yes, the third thing was games. Trivial Pursuit had just come down from Canada to the US about 18 months earlier. I had this idea that we could invent games and get ahead of Milton Bradley and Parker Brothers – and companies like Waddingtons, Spear’s, Peter Pan and Merit in the UK. Nobody had trained game developers for adult party games. I was 28 and thought “I can do that”.

At the time, it felt like we could’ve gone in any direction but looking back now, I had been planning to run a games company all my life – but didn’t know it! I was the oldest of five kids and we probably had 200 board games in our house. When we weren’t playing outside, we were playing games.

Then I got really interested in trivia at college and I hosted this organisation called Stanford Lovers of Unusual Trivia. It was cool because Stanford was thought of as a place where the best and the brightest went to do serious studying, but here we were, answering trivia questions about music, movies, sports and television!

So looking back, I think I was gearing up to be a games creator without realising it. Once we started the company, I realised how much I loved inventing and developing games and I worked hard to be more accomplished at it.

Well, the ice cream and beer industries’ loss has been our industry’s gain. And there’s still time Bob…

Exactly, I still want to do a brewery! I still drink a lot of beer and eat a lot of ice cream, along with playing a lot of games, so I’m doing my bit for all three industries.

Ha! And am I right in thinking your first game was Murder Mystery Party?

Yes, Murder Mystery Party really set the stage for how we identify what we’re trying to do. You talk to a lot of companies and a lot of inventors, and everyone has different ideas about what they’re trying to accomplish and trying to contribute. We thought that games didn’t need to have a board, or a start and a finish, or to end with one person winning and everyone else losing. In 2022 this doesn’t sound like any great epiphany, but in 1985 it was!

The games of that era were games like Trivial Pursuit, Monopoly and Snakes & Ladders. We wanted to be a company that developed social interaction games, where the enjoyment would come from the experience, not from the competitiveness of winning or losing.

Murder Mystery Party took something that was already going on – Murder Mystery weekends – and put in a box. It was our first game, it focused on social interaction, and we’ve been doing that kind of game ever since.

I’m interested… That kind of thinking around games was obviously ahead of its time, so was it a tough sell when it came to retail?

The reaction from the traditional toy retailer was: “Let’s see if I’ve got this straight… You’re going to sell me a game that can only be played once, has no board, has to have eight players… And you expect me to stock it in my store, where children are, while it has the word ‘Murder’ written big on the box?”

Sounds like a tough sell!

I said: “Think of it this way… It’s an evening of entertainment. Think about how much you’d spend if eight people went out to a movie. This game is a huge bargain. We’ve even included invitations so you can send invites out to the other people ahead of playing the game.” That’s usually when the buyer would say: “Wait, you also have to pre-plan it a week in advance!?”

We very quickly learned that this was not going to be something traditional toy stores would go for.

Who did embrace it?

The hobby game stores understood it better, but the people who really built our business in the first couple of years were department stores and catalogues. In the UK, it was places like John Lewis – but we didn’t sell in the games department; we were in the men’s accessories department. We learned to go to places that other people who sold toys didn’t go.

Now, when we look for distribution for a product, we don’t approach from the point of view of selling our games solely to games departments. We sell our games where people shop. We’ve been the most aggressive in the category when it comes to opening up new channels. We were one of first to enter bookstores, electronics stores and DIY stores. In Australia, we’ve been the first to sell some of our games in sex shops!

I won’t ask which game! Has that attitude from toy buyers changed much? Are they more open to innovation than they were back in 1985?

I think Cards Against Humanity and What Do You Meme? opened it up a little bit, but we still encounter that conservative way of thinking.

One of our bestselling games in the UK is Smart Ass, a really fun game. In the US, we have retailers that require us to do a version where we put an Asterix in so it reads ‘Smart A**’. They’re selling guns in the store, so guns are okay but the word ‘Ass’ isn’t!

It also took me years to get Battle of the Sexes – a game that Spin Master has now – into Toys R Us at the time. They didn’t want the word ‘Sex’ in their stores… So it still happens, but it’s nowhere near as tough as it was back in 1985.

The Smart Ass example is a strange one; you’d think the image of the donkey would put minds at ease! Let’s move on and talk about inventors. Can you recall your first encounter with the inventor community?

Well, in the beginning, you don’t have external inventors coming to you because nobody knows who you are. However, when you start a business, you have dreams. One of mine was to invent a game that was good enough for Milton Bradley or Parker Brothers to license from me. So I did some research into how that all works and I learned about the inventor community; this would be when the company was around three years old.

To answer your question, one of the first invention companies we met with was Seven Towns, but the first people we licensed a game from were not game inventors by profession. There was a young boy whose parents were really pushy! He’d invented a dinosaur game called Dinomite. They got hold of us, submitted the game and dinosaurs were popular, so we put the game out.

That actually led us to develop the National Young Game Inventors Contest. We did that for around 15 years and we’d publish the winning game each year. So our richest source of external ideas in the late Eighties/early Nineties came from children! We’d give the winners a $10,000 scholarship for education.

The other early game to come from an inventor was Kids on Stage. It came from two teachers in Missouri. I grew up in Missouri, they knew my family and got the game to us somehow!

What excites you about working with inventors?

Well, everyone likes to say – particularly if they’re talking to you – “We’re so inventor friendly, we love inventors, we couldn’t survive without inventors.” We aren’t quite there because most of our games are developed in-house. But we do something that most companies don’t do; we analyse the success of our games! And as an overall batting average, it’s indisputable that the games we license from inventors do better than the games I invent, or the ones we do internally.

So we wouldn’t be the company that we are if we didn’t have a mix. We license three to five games from inventors each year, and if you look at our top ten games, inventor games are usually in there.

That’s encouraging to hear. If we dive into pitching, what do you think makes for a strong inventor pitch?

Personally, I don’t like to make game decisions based on looking at sizzle videos, but I know that’s ‘the thing’ in the industry. Craig Hendrickson, our SVP of Marketing and Product Development, is much more comfortable with it, but I like to play the game. Look, I’m still an inventor at heart; I genuinely want great games to get out there. Some companies want 30 second YouTube videos that will go viral. I want games that play well!

So the first tip I would give inventors is figure out a way for us to actually play the game, and if the game isn’t developed enough to be playable, we’re never going to do it.

A second tip would be: research the competition. It’s not helpful to show us a game when you don’t know that there’s three other games on the market with basically the same mechanics. But if an inventor is upfront and says: “Here’s my game, there’s three other games out there like this, but here’s why mine has the edge” That’s great.

My last piece of advice for inventors would be: tell us what your process is for licensing your idea. Some people tell us its first come first serve, others will put us on hold until they know if a bigger company wants the idea – and for some, it’s about money. And all of those things are okay, but just be straightforward with us, because it’s not just about licensing the game, We’ve got to get along with the person too.

On the flip side, what makes for a bad pitch?

The thing that annoys me most in a pitch is when the inventor doesn’t know how to play the game. It drives me crazy. Or they say: “I haven’t quite figured this out, it could have five different rules here.” I don’t find that interesting! We can always make rules better if there’s a way to make it better, but if they can’t figure out the best way to play their game, then I don’t have confidence in it.

One last thing would be… Don’t tell me that your game is going to be bigger than Monopoly, or Pictionary, or Trivial Pursuit. Most inventors have a limited idea of how the commercial side of the business works, and the fact that their friend told them they like it better than Monopoly doesn’t mean they’d buy it over Monopoly.

Avoid hyperbole, because most people see through it right away. Be confident about your game, but don’t tell me it’s the best game that’s ever been invented.

Good advice. What do you think is the key to successful inventor/company relationships?

On the inventor side, integrity is really important.

If I meet with you, and you say to me: “You can have this game globally.” And then a month later, just before signing the contract, you tell me: “You’ll still get the UK, the US and Canada, but I got a higher offer for Australia. I hope that’s okay?” With other companies, that might be fine, but with University Games, we’ll just walk away. We had a deal, you broke the deal for money, and we won’t forget that.

Integrity and keeping your word is really important.

And on the company side?

Regular communication is important. Many companies think that once they’ve licensed a game, their sole obligation is to send inventors royalties. I don’t know if we do this every time, but I like us to send packaging ideas to the inventor or have them review a game’s content to ensure its true to the voice that the inventor wants their game to have.

I also want the inventor to be interested in how we’ll promote the game, and I want us to engage with them on that. If we do all those things, we’re a better company for the inventor to work with.

You also do licensed games. What do you look for in a brand to work with?

Every game we have is designed to have some type of learning, either developmental, curriculum-based or – if it’s a party game – it’s social and about learning about each other. That’s a template that we put on top of every licence.

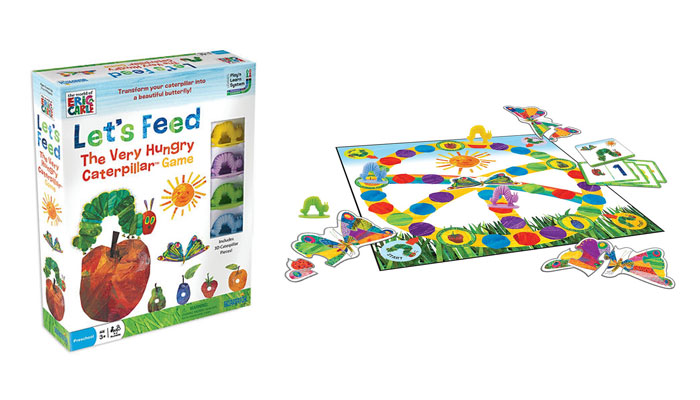

We like licences that are literary based. We were the first company to do a Harry Potter license for games and puzzles. We put ours out the same month that Mattel put theirs out. We were also the first games and puzzles licensee for Dr Seuss. We had that license for 12 years. We feel we can take a great book and bring it to life. Currently we are marketing games based on Roald Dahl, I Spy, and Richard Scarry book title. Our longest running licensed games line is Eric Carle’s book line headed by The Very Hungry Caterpillar.

We also like educational TV shows, like PBS and BBC shows. We, along with Hasbro, were the first in the US to launch Teletubbies into games and puzzles. And we do a lot of game show games. In the UK, Upstarts – a company we acquired – launched the Who Wants to be a Millionaire? board game. In Australia we’ve done a lot of game show games too.

Speaking of acquisitions, some recent news is your acquisition of Forbidden Games. It’s a move that gets University Games into the strategy games market. Talk us through the thinking behind the acquisition.

When you’ve been in business as long as I have, you end up having lots of old crap in your office! I found an old pie chart detailing the sectors within the board game industry from the Eighties. Back then, ‘Strategy Games’ was a tiny little slither of 3%. Now, it’s more like 15%. We like to look at trends and if we see a category growing, that’s a ‘check’.

Then we look at consumers. For strategy games, it’s no longer just high school and college-aged men playing these games. Now men, women and children are playing strategy titles. That was another ‘check’

The next ‘check’ came by looking at retail. In the US, there are 10 to 15 strategy games sat right there next to Monopoly at mass market retailers. They’ve come to where our bread and butter is; it’s not just limited to hobby stores.

The last thing is the price point. The world is now accepting $40 or $50 price points for games of this type.

When did you decide this was a sector you wanted to be involved in?

Four years ago. That’s when we decided we wanted to get into the strategy games market, but no-one on the team knew how to invent strategy games! We knew how to play them, but not how to invent them!

We were waiting for the right thing to come along and Glenn Drover’s Forbidden Games is that right thing. We’re so excited – and we managed to find a company that Asmodee hadn’t already bought!

Have you played any of Forbidden Games’ titles?

I haven’t, but I’ve ordered a copy of Raccoon Tycoon; it looks right up my street.

We’ll be launching it in the UK next year. When I played Raccoon Tycoon, it was the first game since Exploding Kittens that once I’d finished playing, I wanted to play it again right away. And it’s not a 15-minute game; it takes between an hour and an hour and a half to play. Lizard Wizard is also really good, and so is Pirates and Railroad Rivals – and the upcoming Mosaic will be the best of all of them

Bob, this has been great. I have one last question: what fuels your creativity?

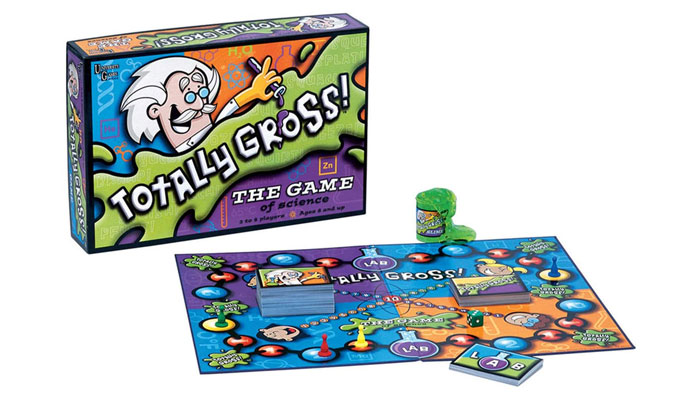

There are two different kinds of ideas that I get in my role as President of University Games. The first is game ideas. That usually comes when I’m with other people. We’ll be having a chat and it’ll spark a game idea that I’ll have to write down. It could be something as vague as ‘Game about science involving poop and vomit.’ That became our Totally Gross game.

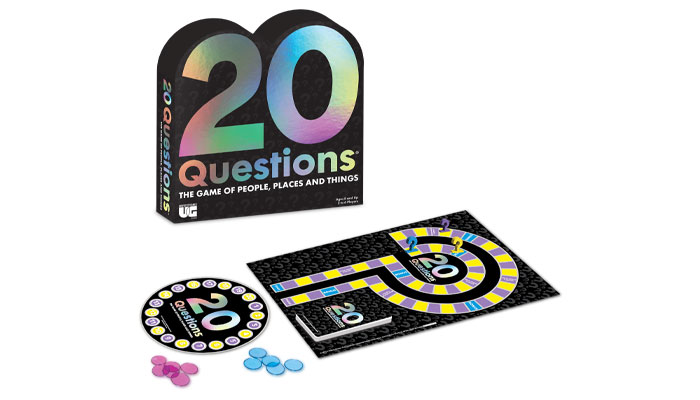

Before coming up with 20 Questions, I wrote down ‘A game for people who hate Trivial Pursuit’ because I was talking to people about Trivial Pursuit. So game ideas usually come through conversations.

The other types of ideas I have are business strategies, and those are more scheduled. I’ll go and watch a baseball game and I’ll bring a pad with me to jot down thoughts about new ways to market our games. I need to be somewhere where there’s something going on to clear my mind, I usually need a beer or a glass of wine, and I need a pad of paper and a pen. I have around 300 pads filled with business ideas.

And what kills creativity for you?

For most people, brainstorming is really bad for getting the most creative idea. The really great ideas are not going to be for everybody, so when you have a bunch of people brainstorming, you work towards the mediocre idea. Great ideas get disbanded in brainstorms even though the whole idea of a brainstorm is to NOT throw out any ideas.

Another thing that’s bad for creativity for me is getting too involved in my business. There’s some logic to the idea that creatives are different to businesspeople. When I have to deal with accounting or HR and very detailed or complex issues, it can take me a week to get back to feeling creative… It can really suck the creativity out of me.

Fascinating stuff. Bob, this has been great. Thanks so much for sharing your insights and let’s catch up again soon.

–

To stay in the loop with the latest news, interviews and features from the world of toy and game design, sign up to our weekly newsletter here