Wynne-Jones’s Victor Caddy discusses the red flags and legal snags behind one inventor’s nightmare

Victor, thanks for joining me. We recently discussed a case that I thought it would be helpful to share – so far as we can – since it gives a glimpse into an inventor nightmare. It’s not something you actually worked on, though?

That’s right. It’s not a Wynne-Jones case. And frankly, if the inventor had been our client – at any stage – we would’ve given her some simple advice to avoid the whole mess she got into.

Alright. But it’s now come to your attention, and you’ve learned a bit more through the public record… Obviously, we don’t know the people involved, but I still don’t want to say anything that pains anyone. So if you think we’re sailing too close to the wind, just let me know through the medium of a horrified scream.

A horrified scream? Hopefully it won’t come to that.

Let’s find out! So… Hearing this story, it seems to me that a new inventor brought an idea to fruition, but on a modest scale…

I think modest is a good word here, yes. She’s making a toy, quite a novel idea, I thought, in a bit of a cottage industry. She’s selling this toy here and there to gift shops and markets, Christmas fairs and the like.

Great. But after a short while, a self-styled entrepreneur sees the idea and wants to manufacture and distribute it on a larger scale.

Right. It must have seemed like a breakthrough moment for the inventor – and flattering too. It’s worth saying, though, that the inventor had never done a licensing agreement before. It’s not clear whether or not the entrepreneur had because he wasn’t in the toy business, but the inventor certainly hadn’t.

Good point. Also, I’m going to be clear that the entrepreneur isn’t in the toy business now either… Because what I don’t want is for people to be reading this just for tittle-tattle, thinking: “Who’s the inventor?”; “Who’s the entrepreneur?”

No, that would be missing the point.

So in terms of early warnings, then, is there already a red flag in as much as it’s a new inventor AND an entrepreneur from outside the industry?

Well, not a legal one, no. I think a couple of things we’ll discuss in this case aren’t necessarily a problem in and of themselves. Orange flags rather than red ones, maybe.

Orange flags! I like that…

For me, that’s a key point here. How does an inventor, who isn’t a legal expert, know when two or more orange flags have the cumulative effect of a red one? In this case, a number of problem issues are present together. There’s an inventor on the outskirts of a new industry, and an entrepreneur also on the outskirts of a new industry. You could argue that that is a red flag – it’s certainly two orange ones with the propensity to add up to the same thing as a red one.

Yes, certainly there might be a problem with the clueless leading the helpless. Then again, some people do very well like that! For now, though, these two people are just talking about moving forward… So what IS the first real red flag?

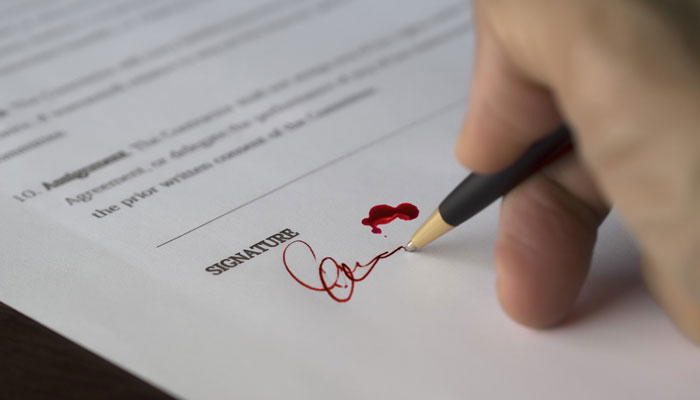

The first real red flag is that – at a meeting arranged to discuss next steps – the entrepreneur arrived with a solicitor in tow, unannounced. Now, it seems to me that if one party unexpectedly turns up with a solicitor, that might be a pretty big warning sign. And in this instance, the solicitor had a contract in hand…

Right. It’s fair to say that there aren’t many situations in which one would be encouraged by the surprise appearance of a solicitor! Do we know what the contract said?

Not entirely. But the entrepreneur had it drawn up, and said it would ensure the inventor would get paid a royalty if they agreed to work together. And again, that MIGHT be perfectly legitimate. My general advice, though, would be obvious and simple: be VERY careful. I think we all have to remember that anyone who’s advising one party in relation to a particular matter can’t also be advising another.

Their solicitor can’t be your solicitor…

Exactly. Everyone needs their own dedicated advisor because no two parties ever have identical interests on all aspects of a matter. It’s amazing how often we come across this in real-world examples. In this instance, the inventor said she wanted time to think it over, but was told it was too urgent… That there were orders on their way, that sort of thing. So she felt pressure to sign there and then. Now that’s a huge red flag!

Right! “Here’s a legal document. Take all the time you need. Hurry up!” So… A couple of small orange flags – maybe – both parties are completely new to the industry. Big red flag: entrepreneur unexpectedly shows up with a solicitor. HUGE red flag: pressure to sign a document…

Yes. You just can’t let yourself be rushed into doing these things, no matter what the circumstances. Take your time and do your research before making any commitment. But let’s just suppose the company was being straight with the inventor at this point. The rush could still be a red flag, don’t you think?

I would think so; very much…

Because even if there’s no duplicity there, it would mean that the company’s gone ahead and got orders before having a deal with the inventor. With all the benefit of the doubt you could muster, what would that say about the way they’re conducting their business? At the very least it suggests they’re not very good at dotting the i’s and crossing the t’s. It’s a red flag either way.

Exactly! And this isn’t a legal point, but I noticed that the inventor described both of these men as “really charming”. Pain me though it does to say this, that word always gets my attention… It’s astonishing how often victims describe conmen, cult leaders, abusive partners, sociopaths or manipulators as “charming”.

I think being charming comes with the part. If they’re charming, you’re more likely to think they’re on your side. But the horrid truth is that you have to pretend to be a nice guy to get away with aberrant behaviour…

There’s a book on some aspects of that by Sandra Horley. In any case, for better or for worse, these two men are charming. And here they are: they’ve hijacked the inventor with a legal document, and they’re applying pressure. The next thing that seems odd is that they’d already bought a domain name relating to the product.

Yes, claiming that it had to be registered with them for admin reasons… They also said the inventor should assign her trademark to them so the company could more easily expand into other countries.

Assign!

And at this point the red flag is as big as it gets. The fact that they asked the inventor to assign them the trademark makes these people sound like a bunch of crooks!

Crooks! Oh my goodness! Should one of us be giving a horrified scream?!

Well – we’re being very careful… But that’s pretty low. She needed legal advice. And this can be difficult if you don’t have deep pockets. Intellectual property attorneys and lawyers aren’t cheap, and you really don’t want to be incurring big costs before you have revenue or royalties coming in. It’s a catch 22.

Yes…

Even so, there is an organisation called IP Pro Bono, which is a collaboration of a number of leading IP organisations, including my own – the Chartered Institute of Trade Mark Attorneys – which aims to provide a pro bono service for people who need advice and aren’t in a position to pay for it. However, I’m sorry to say that it’s currently inactive, although – hopefully – that’s only temporary.

What would be your current advice, then?

What I’d say to anyone in the position this inventor was in is this: make a few phone calls to patent and trade mark attorneys or IP solicitors. Ask if they’ll give you an initial free consultation. Some firms won’t! Some will…

The initial consultation is free?

Yes – even then, this is unlikely to cover the full cost of the advice you need. I do wish more attorneys would take a longer-term view or a more imaginative or flexible approach, though… In this instance, the inventor needed – right at the start – someone who’d just act as a legal friend for her. A mentor, if you like.

Right – not even a fully qualified trademark attorney, necessarily… Just someone with a bit of insight; a bit of legal savvy?

Exactly. Obviously, the more qualified they are, the better – but it would’ve taken someone with even just a little insight less than half an hour to put her on the right track here.

And what IS the right track?

Really, it’s pretty simple: first, it should have been a licence agreement, not an assignment.

This is a critical point: for the uninitiated, what’s the big difference?

The big difference is that – with a license – the inventor retains ownership of their intellectual property. In other words, a license grants another party permission to use your IP, or parts of it, usually for a limited period of time.

Whereas with an assignment…

With an assignment, the inventor hands over ownership to someone else. It’s like selling your house instead of renting it.

Gone! The inventor no longer owns the idea…

Right. Or rather, not right. You sign away all your rights!

Ugh. Makes me feel a bit sick… I mean: no one can afford to confuse those two words. It’s the difference between night and day…

Absolutely. And I think you’re right… The idea that an inventor feels pressured into signing a contract that assigns an entrepreneur rights is, frankly, sickening. But let me just back track for a minute because there’s something even more sneaky about what happened here.

Go on!

The agreement the solicitor took along to the meeting was entitled ‘Licence Agreement’, and it did actually include proper licensing provisions. But then it also included a paragraph in which the inventor assigned over her trademark.

One paragraph…

One paragraph. And the truth is that – once she assigned her trademark to them – there was no need for a licence. They then owned the trademark and could do whatever they wanted. All the licensing provisions in the agreement were made redundant by that one assignment paragraph.

Crikey. It really does feel like an outright con, doesn’t it? It doesn’t seem likely to be a mistake…

No… And that leads to my second point. On day one, the company should have been made to assign the domain name to the inventor. There should have been a crystal-clear delineation. One party – the inventor – owns everything, and the other party – the company – was permitted by the inventor to do certain things. So the assignment of the trademark from the inventor to the company should have been taken out of the agreement, and an assignment of the domain name from the company to the inventor should have been put in.…

So – sorry; hang on! Let me get this clear… Because the domain name directly related to the product name, the inventor would’ve been better off registering it in their name?

Yes. A domain name is not intellectual property, in the way that a trademark is. Rather, use of a domain name is use of the underlying trademark.

Got it. So they should be including THAT as part of the licence agreement?

Exactly. Use of the domain name should’ve been one of the things the inventor permitted the company to do under the terms of the licence.

Okay. Was there a third thing?

A third and a fourth! Third, the company should’ve agreed – again, in the licence – not to claim any ownership rights in the name or names derived from it… And fourth – if the company wanted rights in other jurisdictions, or more rights in the UK based on variations of the product name – those rights should’ve been filed in the inventor’s name… But at their expense, with the licence extended accordingly. It’s very easy to add trademarks to an existing licence agreement, while keeping the terms of the licence the same. You just need something called a novation agreement, which is usually just a one page document.

A novation agreement? Okay… It’s all the wrong way round! And it becomes a bit of a sticky wicket from this point on, presumably, because – under pressure and misguided – she signed the agreement…

Yes. I am afraid she ran herself out. She gave away all her power and control and left herself with nothing. And things got messy when she tried to terminate the agreement because they wouldn’t accept the termination. They said she no longer had any rights, and so there was nothing to terminate. And I’ve no doubt, by the way, that a legitimate company would’ve agreed to the things she should have demanded on day one if they were hot on the business opportunity.

And an attorney – or legal friend – could’ve steered the inventor that way? Or pointed out the potential pitfalls of these conditions?

Absolutely! And they could easily have included, in the agreement, a stipulation that foreign or extra UK trademark applications had to be filed through them. That would have secured the opportunity of future revenue for themselves in return for half an hour or so of initial free advice.

Oh gosh! I see! I see how that ties into what you were saying earlier… Right. In giving the inventor a little bit of free advice, the attorney – very openly and fairly – could secure fee-paying opportunities as the deals went ahead.

Yes. You hear the words win-win used quite a lot – and not always correctly! But here it really would be a win-win: the inventor gets better-quality advice, the attorney lines up future work. And the agreement has the best chance of being successful so everyone wins for years ahead.

Right. And I understand the inventor – in hindsight – used another word that’s not always employed correctly… ‘Gaslighting’. She felt that every time she asked a question, or complained about something that didn’t make sense, the entrepreneur gaslit her; made it feel like any issues stemmed from her lack of knowledge; her own insecurity and naivety.

Yes. Crooks! But this is what it comes down to: would they have behaved like this if she’d had that vital ‘legal friend’ on her side from day one? Sadly, I think the way things panned out, she gave the impression that she was a push over.

They must’ve been like sharks smelling blood in the water…

Clearly, they’re the kind of people who’d exploit this. And perhaps I should say that this inventor was very, very unlucky. I don’t think most people are like that. Certainly, in my experience, it’s quite rare inside the toy industry, where the community is pretty close and reputable. But sadly business is business. There are sharks closer than you think even at the safest beaches…

Bloody Hell! It’s like the 4th of July on Amity Island! And from the sound of it, this product got to market and did okay for a brief time. They also weren’t very open about those royalties that they eventually said they’d pay her, though…

No. There’s a report from the Intellectual Property Office, the IPO, that suggests the company wasn’t exactly straight. It’s quite shocking. So it must’ve been galling to see the product out there. Also, there’s something else that this document throws up which might be a useful road sign for new inventors…

Oh?

It’s always worth doing a check against people’s names and company names. It’s very easy to do; it doesn’t even cost anything. Just by way of example, if you go to the Companies House website and type in someone’s name, you’ll see how many companies they’re listed as a director for… And if a lot of them are dissolved, that tells you something. That’s potentially a red flag right there, or at least cause to ask questions.

Umm-hmmmm…

It’s also worth searching the UK IPO website for decisions involving someone, or their company. It’s amazing what facts come to light in these cases. And a third thing that’s worth checking – and again you can do this yourself, free and online – is domain name dispute records. That would’ve been a good idea here, where the entrepreneur jumped the gun in registering the domain name. He might very well have been a serial cyber squatter, registering domain names that didn’t belong to him.

Oh, that’s brilliant… Any of these things would absolutely be a red flag, Victor; those are really great tips…

And, by the way, currently, the person we’re talking about now seems to be trading under another name… But that name doesn’t seem to be a registered company. There’s a company registration number on his Facebook shop, but it’s for a DIFFERENT company…

My God; you’ve turned into Columbo!

There’s just one more thing… That’s bothering me! The registration number still up on his Facebook shop is not only for a different company – it’s for a DISSOLVED company… It’s always a good idea to check things like company numbers on websites and other online platforms. The impression given here is that you’re buying from a legitimate, registered company, but you’re not. Unfortunately for our inventor, the fact that the company is dissolved does rather mean that she has to forget what’s happened and move on.

And that’s probably for the best right now. Well – no; what I mean to say is that – psychologically – it would be very stressful to look at now, I think, and futile.

Right. But in terms of who now owns that inventor’s trademark in this country, that’s back with her. She bravely fought these people at the UK Intellectual Property Office. I won’t go into details for the sake of anonymity, but I think the hearing officer who handled the case did an excellent job and reached a good decision. But IPO cases like these are like mini court cases. It must’ve been a long, tense and expensive process for her.

Right. But also she was young enough at that time, I think, for it to be a USEFUL lesson rather than the purely Pyrrhic victory it first seems.

Yes. Although in that instance, the case only related to the basic UK trademark. The UK IPO has no jurisdiction outside the UK, and, in the meantime, these people had registered the trademark around the world…

So, let me get this right… To fully get back what was rightfully hers in the first place, she’d need to take action in each territory where the mark’s registered?

I’m afraid that’s absolutely correct, Deej. I’d also add that merely getting a decision in your favour at the UK IPO – or any other IPO around the world – is only half the job. It’s up to you to enforce the decision.

Right… It’s one of these bodies that tells you what your rights are, and that you are right. It doesn’t enforce anything for you?

No; unfortunately, the UK IPO is pretty toothless when it comes to enforcing decisions. They just don’t have the powers. Obviously, they can enforce decisions to revoke trademark registrations, or take them away from people who aren’t entitled to them, as they did in this case. But, they can’t go out into the real world and sort things out there…

The best they can do is publish details of cases so that ‘bad operators’ get a bit of exposure. They also publish a list of people who don’t pay the awards of costs they issue in favour of winning parties. But that’s about all they can do. Frankly, quite often the best approach you can take if someone doesn’t pay an award of costs is to make a claim with the small claims court.

I have a horrible feeling I know where this is going…

Yes, well… If you want to do more than this, then yes: I’m afraid you’re back in the position of needing to instruct a trademark attorney or a lawyer again. So, there ought to be a good chance it’s going to be financially worthwhile, and you have to have basic capital available that you don’t mind losing if things don’t go the way you want them to.

Yes. And you mention small claims… I guess that’s something else you can do – check out The Register of Judgments, Orders and Fines, or your country’s equivalent. As a public register, you can learn from that – for a small fee – if people have county-court judgements against them.

Yes, you can add that to the searches I mentioned before – those records are kept for up to six years after a judgement, so if people have recently misbehaved, and not payed their debt, absolutely: you can find out that way. It’s not entirely conclusive, of course, but it’s a pretty good litmus test.

Exactly so!

I’m reminded of the fact that, during the Second World War, many bomb-disposal experts – fighting for the allies against the Nazis – lost their lives because the Nazis changed the wiring of their bombs… Only later was it discovered that the new wiring had actually been disclosed before the war in a patent document. It was freely available for everyone to see in the UK Patent Office library in Holborn.

You’re kidding? We already knew? But we didn’t know we knew?

Exactly. And that was tragic, but arguably understandable in its era. Now, though, we live in an age where there’s so much authentic information available online and hence accessible to us in our sitting rooms. We often worry about false things online, but there’s a wealth of authentic stuff too.

Great. That’s an extraordinary story… Well, look, Victor – I knew this would be fascinating to you and me, if no one else. But then, if one new inventor reads this and invests a little bit upfront in legal protection to avoid a court case later, then it would be time and money well spent.

That’s exactly right. As the old saying goes, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” There’s one last thing I think is worth mentioning in this particular instance, by the way. Forget Colombo. This is a Poirot moment…

From the little grey cells …

There’s one glaring omission in everything we’ve discussed, and in the whole case actually… NO ONE THOUGHT ABOUT COPYRIGHT. As you know, I’m a trademark attorney – I swear by the importance of trademarks. But, in this case, the most important piece of intellectual property our inventor had was the copyright in her toy.

And that didn’t come up?

No. That was never mentioned in the agreement or anywhere else, come to that. And what that means is that all the use, all the sales, the entrepreneur made at her expense was actually infringing use. She owned the copyright ALL ALONG. She could have stopped them ALL ALONG. And she could have taken their profits ALL ALONG. As you say, it’s too late now, but – WOW! It makes you think, doesn’t it?

It really does… And you know, you’re right: I completely missed that. It’s not just about what’s in the document – it’s what’s not in that document…

Right. And again, a legal friend would’ve spotted that. I don’t know about you, but this is the moment I feel tempted to let out a horrified scream.

Ha! It’d be therapeutic at this point! And while I’m quite sure she wouldn’t want to at this point, is that something the inventor could’ve pursued? Realistically?

Absolutely, at least while the company was in existence. To be clear, copyright infringement is a complicated and specialist field… From which you can rightly infer it’s expensive! Ideally, you’d want a copyright solicitor to look at that, but if it goes your way in the end, you could be awarded substantial damages. At the time, it might have been worth her looking for someone who would take this on, perhaps on a no-win, no-fee basis. But now it’s too late. There’s no one to sue, no one to get damages from. And, as you’ve said, that’s probably just as well, because it would have been horribly stressful.

Brilliant. Thank you for making time for this, Victor – fascinating. And how now should we sum it up? What are the take-away points?

I think, in this instance, they’re to think about what intellectual property you actually own. You ALWAYS have to think about that. Also, to know the difference between a license agreement and an assignment.

One hundred percent…

Never be rushed by anybody. Have a legal friend look over your dealings, at the very least. And if you do find yourself in the position where you repeatedly have to give people the benefit of the doubt, ask yourself: would a professional company give rise to so many doubts in the first place?

Absolutely fantastic. Victor – thank you SO much. It doesn’t quite go without saying that if anybody wants legal advice in this area, you’re a specialist trademark attorney with the highly respected Wynne-Jones – not to be confused with the Wynne-Jones that sells beekeeping equipment in Wales… What’s the best way to get hold of you?

Ha! I am pleased to see you’ve been putting what I advocate into practice and you’ve been checking up on us on Google! Wynne-Jones has offices in London, Cheltenham and Cardiff. I’m in London, and probably the easiest way to contact me first off is by email, at [email protected].

–

To stay in the loop with the latest news, interviews and features from the world of toy and game design, sign up to our weekly newsletter here